Why is landing on a comet so difficult and what does this tell us about future missions to comets and asteroids?

Us nerds were riveted by the coverage of the ESA’s Rosetta mission and its arrival at Comet 67/P in 2014. One such nerd is Paco Juarez, friend of the show and patron. He wanted to know why is it so darned hard to land on a comet?

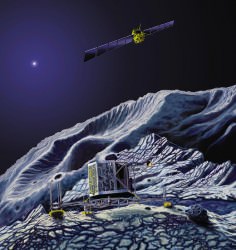

In 2014, the tiny Philae Lander detached from the spacecraft and slowly descended down to the surface of the comet. If everything went well, it would have gracefully touched down and then sent back a pile of information about this filthy roving snowball.

As you know, the landing didn’t go according to plan. Instead of gently touching down on 67/P, Philae bounced off the surface of the comet like a tennis ball dropped from a tower, and rose a kilometer off the surface. Then more descending, and more bouncing, finally settling down on rugged terrain, surrounded by crevices and large boulders. At that point, engineers lost contact with the lander, and so much science went undone.

If I recorded this video a few months ago, that would have been the end of the story. You know how this goes, space exploration is hard and dangerous, don’t be surprised when your missions fail and space unfeelingly smashes up your pretty little robot probes with their little gold foil 27 pieces of flair.

Fortunately, I’m able to report that ESA regained contact with the Philae lander on June 13, 2015, resuming its mission, and scientific operations.

But why is landing on a comet so difficult and what does this tell us about future robotic and human missions to smaller comets and asteroids? When ESA engineers designed Philae, they knew it was going to be very difficult to land on a comet like 67/P because they have a such a low gravity. And they have low gravity because they’re little.

On Earth, 6 septillion tonnes of rock and metal give you an escape velocity of 11.2 km/s. That’s how fast you need to be able to jump in order to leave the planet entirely. But the escape velocity of 67/P is only 1 m/s. You could trip off the comet and never return. Whilst small children threw rocks at you from the surface as you drifted away.

Philae was built with harpoon drills in its landing struts. The moment the lander touched the surface of the comet, those harpoons were supposed to fire, securing the lander. The surface of the comet was softer than scientists had anticipated, and the harpoons didn’t fire. Or possibly they were broken and couldn’t fire. Space is hard. Whatever the case, without being able to grab onto the surface, it used the comet as a bouncy castle.

We’re learning what it takes to land on lower mass objects like comets and asteroids. NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission will visit Comet Bennu, and send a lander down to the surface of the asteroid. From there it’ll pick up a few samples, and return them back to Earth. It’ll be Philae, all over again.

In the future, we’re told, humans will be visiting asteroids to study them for science and their potential for ice and minerals. You can imagine it’ll be a harrowing descent, but even just walking around on the surface will be dangerous when every step could throw an astronaut into an escape trajectory. They’ll need to learn lessons from rock climbers and Rorschach.

As we learned with Philae, landings on low mass objects is really tough. We’re going to need to get more practice and develop new techniques and technologies before we’re ready to add asteroid mining to our list of “stuff we just do, NBD”.

What are some unusual worlds you’d like humanity to visit? Put your suggestions in the comments below.