So, just how do we keep our space stations, ships and astronauts from being riddled with holes from all of the space junk in orbit around Earth?

We revel in the terror grab bag of all the magical ways to get snuffed in space. Almost as much as we celebrate the giant brass backbones of the people who travel there.

We’ve already talked about all the scary ways that astronauts can die in space. My personal recurring “Hail Mary full of grace, please don’t let me die in space” nightmare is orbital debris.

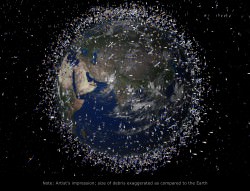

We’re talking about a vast collection of spent rockets, dead satellites, flotsam, jetsam, lagan and derelict. It’s not a short list. NASA figures there are 21,000 bits of junk bigger than 10 cm, 500,000 particles between 1 and 10 cm, and more than 100 million smaller than 1 cm. Sound familiar, humans? This is our high tech, sci fi great Pacific garbage patch.

Sure, a tiny rivet or piece of scrap foil doesn’t sound very dangerous, but consider the fact that astronauts are orbiting the Earth at a velocity of about 28,000 km/h. And the Tang packets, uneaten dehydrated ice cream, and astronaut poops are also traveling at 28,000 km/h. Then think about what happens when they collide. Yikes… or yuck.

Here’s the International Space Station’s solar array. See that tiny hole? Embiggen and clarinosticate! That’s a tiny puncture hole made in the array by a piece of orbital crap.

The whole station is pummeled by tiny pieces of space program junk drawer contents. Back when the Space Shuttle was flying, NASA had to constantly replace their windows because of the damage they were experiencing from the orbital equivalent of Dennis the Menace hurling paint chips, fingernail clippings, and frozen scabs.

That’s just little pieces of paint. What can NASA do to keep Sandra Bullock safe from the larger, more dangerous chunks that could tear the station a new entry hatch?

For starters, NASA and the US Department of Defense are constantly tracking as much of the orbital debris that they can. They know the position of every piece of debris larger than a softball. Which I think, as far as careers go, would be grossly underestimated for its coolness and complexity at a cocktail party.

“What do you do for a living?”

“Me, oh, I’m part of the program which tracks orbital debris to keep astronauts safe.”

“So…you track our space garbage?”

“Uh, actually, never mind, I’m an accountant.”

Furthermore, they’re tracking everything in low Earth orbit – where the astronauts fly – down to a size of 5 cm. That’s 21,000 discrete objects.

NASA then compares the movements of all these objects and compares it to the position of the Space Station. If there’s any risk of a collision, NASA takes preventative measures and moves the Space Station to avoid the debris.

The ISS has thrusters of its own, but it can also use the assistance of spacecraft which are docked to it at the time, such as a Russian Soyuz capsule.

NASA is ready to make these maneuvers at a moment’s notice if necessary, but often they’ll have a few days notice, and give the astronauts time to prepare. Plus, who doesn’t love a close call?

For example, in some alerts, the astronauts have gotten into their Soyuz escape craft, ready to abandon the Station if there’s a catastrophic impact. And if they have even less warning, the astronauts have to just hunker down in some of the Station’s more sturdy regions and wait out the debris flyby.

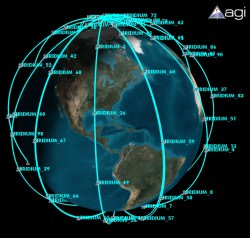

This isn’t speculation and overcautious nannying on NASA’s part. In 2009 an Iridium communications satellite was smashed by a dead Russian Kosmos-2251 military satellite. The collision destroyed both satellites instantly. As icing on this whirling, screaming metallic orbital-terror-cake, it added 2,000 new chunks of debris to the growing collection.

Most material was in a fairly low orbit, and much of it has already been slowed down by the Earth’s atmosphere and burned up.

This wasn’t the first time two star-crossed satellites with a love that could-not-be had a shrapnel fountain suicide pact, and I promise it won’t be the last. Each collision adds to the total amount of debris in orbit, and increases the risk of a run-away cascade of orbital collisions.

We should never underestimate the bravery and commitment of astronauts. They strap themselves to massive explosion tubes and weather the metal squalls of earth orbit in tiny steel life-rafts. So, would you be willing to risk all that debris for a chance to fly in orbit? Tell us in the comments below.