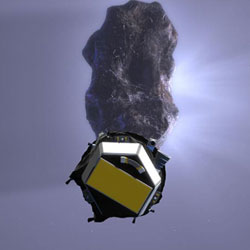

Deep Impact’s impactor module on a collision course with Comet Tempel 1. Image credit: NASA/JPL. Click to enlarge.

Listen to the interview: Get Ready for Deep Impact (6.1 MB)

Or subscribe to the Podcast: universetoday.com/audio.xml

Fraser: Can you give me a preview for what we’re going to be seeing on July 4th?

Dr. Lucy McFadden: I wish I knew exactly what was going to happen on July 4th, but this is an experiment. I can tell you what we think we might see, but chances are it may be significantly different.

So, we have a spacecraft on its way to Comet Tempel 1, which is a short-period comet that orbits – comes into the inner solar system – about once every 5.5 years. It is about the size of Washington DC. It can be fit into the area of Washington DC, but it’s a little bit elongated. It’s about 14 km by 4 km by 4 km, and as our spacecraft is heading toward it, we have planned to actually separate the spacecraft into two parts. Let me set the stage here, this comet is in orbit around the Sun. It’s coming to its closest point of the Sun, called its perihelion, and thus be moving at its fastest speed through the solar system in early July. Our spacecraft is also in orbit around the Sun, and it’s heading to intercept the orbit of the comet. 24 hours before we plan to impact this comet, we’re going to separate the two spacecraft, the impactor and the flyby. The impactor will continue on its collision course to the comet, and the flyby – or mother ship – will slow down a little bit and change its direction ever so slightly so that it will be able to watch as the impactor hits the comet. When it hits the comet, when we have this cosmic collision in space, what’s going to happen is the energy of the impact is going to propagate into the comet itself, in the form of a shock wave. This shock wave will plough into the comet; how deep, we don’t know. But at some point, the force of the material in the comet itself will push back on the advancing energy shock wave and push material out of the comet. We will have formed a crater with ejected material coming out of the hole that we created.

Now, you may ask, why are we doing this? We’re doing this to take a look – to take advantage of the opportunity of this comet being so close to us – to take a look at the inside of the comet; to see what the inside is made of, and see what structure is there.

To elaborate more, I think I need to give you some perspective on what comets are, and what they are in the solar system. I like to say they’re the oldest and coldest part of the solar system. They formed at the edges of the solar system, hundreds of thousands of times the distance that the Earth is from the Sun. So, everything where comets formed is cold. They also formed 4.5 billion years ago, when the solar system was forming. They have never been incorporated into a planet. So they’re both old and cold as well. We’re taking advantage of the comets coming closer to the Earth to use it as a laboratory and as a probe to distant edges of the solar system in both space and time.

Fraser: Now, Deep Impact only launched a couple of months ago, so did we get really lucky with Tempel 1 being at the wrong place at the right time?

Dr. McFadden: Yeah, well, from my perspective it was at the right place at the right time.

Fraser: I was more looking from the perspective of the comet.

Dr. McFadden: Let me say two things here. First of all, the comet isn’t going to be harmed. Let’s get some perspective here in terms of the mass of the spacecraft versus the mass of the comet. Or the energy of the spacecraft versus the energy of the comet in motion. It’s equivalent to a gnat, or a small mosquito being run into by a 767 aircraft. So, we’re not going to hit the comet. But, needless to say, I’ll let you take the perspective of the comet if you want. But yes, it was in the right place, or the wrong place, at this time. NASA said, when it issued its announcement of opportunity for space exploration missions, they said that this announcement covers money available within a certain time frame, and the time frame was between 2000 and 2006. And so, we went looking for comets that were available during the time NASA would give us money, and then when we found Comet Tempel 1 close to perihelion, when it’s moving fastest, that also pleased us because the faster the comet’s moving, the more energy involved in the transfer to create the crater. So, it’s good from that point of view. And then there’s a third, but secondary reason why Comet Tempel 1 is good; it’s not as active as some comets might be. There’s not as much dust and jet activity associated with Comet Tempel 1, which might be confusing or make it hard for us to actually observe the formation of the crater when we hit it. So, Comet Tempel 1 fits.

Fraser: How are we going to be observing it from here on Earth and from space?

Dr. McFadden: We have the spacecraft observing it from space – our Deep Impact spacecraft. We have the Rosetta spacecraft, which is heading to another comet, will also observe it from space. We have NASA’s three Great Observatories: Chandra, Hubble and Spitzer will be observing it. Three different wavelengths; Chandra’s an X-ray telescope, and Hubble’s an optical and near-infrared imaging telescope. We’ll be observing some spectroscopy with Hubble too. And then Spitzer’s an infrared telescope. So, we’ll be using those. As well as all the major observatories around the world will be observing the comet, before, during and after impact. So we’re having a worldwide observing campaign.

Fraser: And how will the pictures from Deep Impact compare to the pictures we saw from Stardust?

Dr. McFadden: It’s interesting, I’m using the images from Stardust to practice interpreting the images we get from Deep Impact. We will get a closer look at Comet Tempel 1 than the Stardust spacecraft did; we will be flying closer – we’ll be flying 500 km from Comet Tempel 1, whereas the Stardust spacecraft was 1,100 or 1,300 km distant.

Fraser: I remember that Stardust got hit quite a bit by debris, how will Deep Impact do if it’s going to be closer to the comet?

Dr. McFadden: You have to remember that the main objective of Stardust was to collect dust, so, they wanted to get hit. So they flew into the region with the largest dust density. What we do when we fly through that same region is we turn the spacecraft away into shield mode to protect the telescope during the time when we should be getting the greatest number of hits from dust and debris. And we actually fly at an angle. Most of the debris exists in the plane of the orbit, in the direction of its motion, and so the spacecraft will fly past it at an angle; so there’ll be a short, 20 minute period when we will not be observing to protect the cameras.

Fraser: Once Deep Impact completes its flyby, will you have any additional scientific targets you’d like to be able to use the spacecraft for, once it gets out of visual range of Tempel 1?

Dr. McFadden: There are currently no specific plans for observing in a follow-on mission; that has to be approved by NASA. We have done some research and know that there are another comet or two that we could observe, but we haven’t gotten approval for that yet.

Fraser: So, in your wildest dreams, what will turn up on July 4th?

Dr. McFadden: Well, my wildest dream is that the impactor will go into the comet and come out the other side, but that’s not very likely.

Fraser: Okay then, maybe a less wild dream.

Dr. McFadden: Okay, less wild, in order of probability is that the comet will have the consistency of a brick, for example, and the impactor will hit it and not do much damage to the surface, or not really create much of an impact because the comet is the consistency of a brick. But that’s not very likely either. On the other extreme, what if the comet is like Corn Flakes? If it’s like Corn Flakes, we should get a spectacular display of ejecta. We call it an ejecta curtain during the formation of the crater, and I’m hoping that that’s what we’ll see, because that would be very dramatic. And hopefully we could watch as we’re taking fast pictures with very short exposures repeatedly. We’ll be clicking as we go by. If we have a big ejecta curtain, we should be able to see the ejecta form, or traveling along in space, and that will allow us to determine the most information about the internal structure of the comet itself. So that’s what I’m hoping will happen.