Image credit: NASA

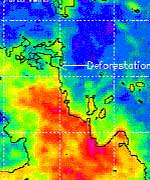

NASA satellite data are giving scientists insight into how large-scale deforestation in the Amazon Basin in South America is affecting regional climate. Researchers found during the Amazon dry season last August, there was a distinct pattern of higher rainfall and warmer temperatures over deforested regions.

Researchers analyzed multiple years of data from NASA’s Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM). They also used data from the Department of Defense Special Sensor Microwave Imager and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites.

The study appeared in a recent issue of the American Meteorological Society’s Journal of Climate. Lead authors, Andrew Negri and Robert Adler, are research meteorologists at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC), Greenbelt, Md. Other authors include Liming Xu, formerly of the University of Arizona, Tucson, and Jason Surratt, North Carolina State University, Raleigh.

“In deforested areas, the land heats up faster and reaches a higher temperature, leading to localized upward motions that enhance the formation of clouds and ultimately produce more rainfall,” Negri said.

The researchers caution the rainfall increases were most pronounced in August, during the transition from dry to wet seasons. In this transition period, the effects of land cover, such as evaporation, are not overwhelmed by large-scale weather disturbances that are common during the rest of the year. While the study, based on satellite data analysis, focused on climate changes in the deforested areas, large increases in cloud cover and rainfall were also observed in the naturally un-forested savanna region and surrounding the urban area of Port Velho, Brazil, particularly in August and September.

Recent studies by Dr. Marshall Shepherd cited similar findings, including an average rain-rate increase of 28 percent downwind of urban areas and associated changes in the daily timing of cloud formation and precipitation. He is also a research meteorologist at GSFC.

This research confirmed the Amazon savanna region experienced a shift in the onset of cloudiness and rainfall toward the morning hours. The shift was likely initiated by the contrast in surface heating across the deforested and savanna region.

The varied heights of plants and trees in the region change the aerodynamics of the atmosphere, creating more circulation and rising air. When the rising air reaches the dew point in the cooler, upper atmosphere, it condenses into water droplets and forms clouds.

Negri acknowledged other factors are involved. The savanna in this study is approximately 100 kilometers (62 miles) wide, the perfect size to influence precipitation, such as rain showers and thunderstorms. Earlier studies hypothesized certain land surfaces, such as bands of vegetation 50 to 100 kilometers (31-62 miles) wide in semiarid regions, could result in enhanced precipitation.

This research is in agreement with the recent and sophisticated computer models developed by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The models concluded small-scale circulations, including the mixing and rising of air induced by local land surfaces, could enhance cloudiness and rainfall. Many earlier studies that relied on models developed in the 1990s or earlier concluded widespread deforestation of the Amazon Basin would lead to decreased rainfall.

“The effects here are rather subtle and appear to be limited to the dry season. The overall effect of this deforestation on annual and daily rainfall cycles is probably small and requires more study,” Negri said. Future research will use numerical models for investigating the linkage between deforested land surface and the cloud-precipitation components of the water cycle.

NASA’s Earth Science Enterprise is dedicated to understanding the Earth as an integrated system and applying Earth System Science to improve prediction of climate, weather, and natural hazards using the unique vantage point of space.

Original Source: NASA News Release