Host: Scott Lewis

Astronomers: Nicole Gugliucci, Chris Kennedy, Tom Nathe, David Dickinson, James McGee

Continue reading “Virtual Star Party – February 9, 2014: Fire is Bad for Seeing!”

Host: Scott Lewis

Astronomers: Nicole Gugliucci, Chris Kennedy, Tom Nathe, David Dickinson, James McGee

Continue reading “Virtual Star Party – February 9, 2014: Fire is Bad for Seeing!”

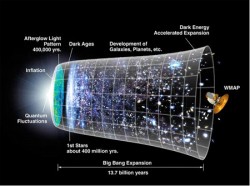

The Universe is vast bubble of space and time, expanding in volume. Run the clock backward and you get to a point where everything was compacted into a microscopic singularity of incomprehensible density. In a fraction of a second, it began expanding in volume, and it’s still continuing to do so today.

So how old is the Universe? How long has it been expanding for? How do we know? For a good long while, Astronomers assumed the Earth, and therefore the Universe was timeless. That it had always been here, and always would be.

In the 18th century, geologists started to gather evidence that maybe the Earth hadn’t been around forever. Perhaps it was only millions or billions of years old. Maybe the Sun too, or even… the Universe. Maybe there was a time when there was nothing? Then, suddenly, pop… Universe.

It’s the science of thermodynamics that gave us our first insight. Over vast lengths of time, everything moves towards entropy, or maximum disorder. Just like a hot coffee cools down, all temperatures want to average out. And if the Universe was infinite in age, everything should be the same temperature. There should be no stars, planets, or us.

The brilliant Belgian priest and astronomer, George Lemaitre, proposed that the Universe must be either expanding or contracting. At some point, he theorized, the Universe would have been an infinitesimal point – he called it the primeval atom. And it was Edwin Hubble, in 1929 who observed that distant galaxies are moving away from us in all directions, confirming Lemaitre’s theories. Our Universe is clearly expanding.

Which means that if you run the clock backwards, and it was smaller in the distant past. And if you go back far enough, there’s a moment in time when the Universe began. Which means it has an age. The next challenge… figuring out the Universe’s birthdate.

In 1958, the astronomer Allan Sandage used the expansion rate of the Universe, otherwise known as the Hubble Constant, to calculate how long it had probably been expanding. He came up with a figure of approximately 20 billion years. A more accurate estimation for the age of the Universe came with the discovery of the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation; the afterglow of the Big Bang that we see in every direction we look.

Approximately 380,000 years after the Big Bang, our Universe had cooled to the point that protons and electrons could come together to form hydrogen atoms. At this point, it was a balmy 3000 Kelvin. Using this and by observing the background radiation, and how far the wavelengths of light have been stretched out by the expansion, astronomers were able to calculate how long it has been expanding for.

Initial estimates put the age of the Universe between 13 and 14 billion years old. But recent missions, like NASA’s WMAP mission and the European Planck Observatory have fine tuned that estimate with incredible accuracy. We now know the Universe is 13.8242 billion years, plus or minus a few million years.

We don’t know where it came from, or what caused it to come into being, but we know exactly how our Universe is. That’s a good start.

Around this time last year a space rock crashed into the Earth above Chelyabinsk, Russia. It brightened the skies for hundreds of kilometers, broke windows and injured many people. Let’s look back at the event. What happened, and what did we learn?

Continue reading “Astronomy Cast Ep. 334: Chelyabinsk”

Just take a look at the surface of the Moon and you can see it experienced a savage beating in the past. Turns out, the whole Solar System is a cosmic shooting gallery, with stuff crashing into other stuff. It sure sounds violent, but then, we wouldn’t be here without it.

Continue reading “Astronomy Cast Ep. 333: When Worlds Collide”

Host: Fraser Cain

Astrojournalists: Scott Lewis, Nicole Gugliucci, Morgan Rehnberg, Brian Koberlein, Elizabeth Howell, Amy Shira Teitel, David Dickinson

This Week’s Stories!

Morgan Rehnberg (cosmicchatter.org / @cosmic_chatter):

New Mars impact crater

Nicole Gugliucci (cosmoquest.org / @noisyastronomer):

Weird Asteroid Itokawa Has a Dual Personality

Shiny new radio image of M82 (but no supernova afterglow)

David Dickinson (@astroguyz):

Venus in 2014

Progress+launches for February

Space History-Curious Artifacts Sent Into Space

Elizabeth Howell (@howellspace):

Astronomy Podcast Enters Sixth Year — And We’d Love For You To Contribute!

Super-Earths Could Be More ‘Superhabitable’ Than Planets Like Ours

Brian Koberlein (@briankoberlein); Scott Lewis (@baldastronomer); & Elizabeth Howell (@howellspace):

‘Wobbly’ Alien Planet Has Weird Seasons And Orbits Two Stars

Amy Shira Teitel (@astVintageSpace):

When galaxies collide!

Scott Lewis (@baldastronomer):

Gaia

We record the Weekly Space Hangout every Friday at 12:00 pm Pacific / 3:00 pm Eastern. You can watch us live on Google+, Universe Today, or the Universe Today YouTube page.

On the morning of February 15, 2013, people in western Russia were dazzled by an incredibly bright meteor blazing a fiery contrail across the sky. A few minutes later a shockwave struck, shaking the buildings and blowing out windows. 1,500 people went to the hospital with injuries from shattered glass. This was the Chelyabinsk meteor, a chunk of rock that struck the atmosphere going almost 19 kilometers per second. Astronomers estimate that it was 15-20 meters across and weighed around 12,000 metric tonnes.

Here’s the crazy part. It was the largest known object to strike the atmosphere since the Tunguska explosion in 1908. Catastrophic impacts have shaped the evolution of life on Earth. Once every 65 million years or so, there’s an impact so destructive, it wipes out almost all life on Earth. The bad news is the Chelyabinsk event was a surprise. The asteroid came out of nowhere. We need to find all the potential killer asteroids, and understand what risks we face.

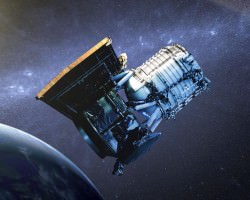

“I’m Ned Wright…”

That’s Dr. Ned Wright. He’s a professor of physics and astronomy at UCLA, and the Primary Investigator for the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer mission; a space telescope that looks for low temperature objects in the infrared spectrum.

“I think the best way to protect the Earth from asteroids is to get out and look very assiduously to find all the hazardous asteroids. Although astronomers have been finding and cataloging asteroids for decades, we still only have a fraction of the dangerous asteroids tracked. The large continent destroyers have mostly been found, but there’s a whole class of smaller, city killers out there, and they’re almost entirely unknown. There are… these dark asteroids that may not be the most dominant part of the population but they certainly can be a very hazardous subset, it’s important to do the observations in the infrared. So you actually, instead of looking for the ones that reflect the most light, you look for the ones that have the biggest area and therefore the ones that are the heaviest and can do the most damage. And so, I think that an infrared survey is the way to go.”

“In the infrared wavelengths, we can find these objects because they’re large, not because they’re bright. And to really do this right, we need a space-based infrared observatory capable of surveying vast areas of the sky, searching for anything moving.”

The WISE mission has been offline for a few years, but WISE is actually being reactivated right now to look for more Near Earth Objects, so we’re currently cooled down to 93 K, and when we get to 73 K, which is where we were when we turned off in 2011 we’ll probably be able to go out and find more Near Earth Objects.

Note: this interview was recorded in November, 2013. WISE resumed operations in December 23, 2013

But to really find the vast majority of dangerous asteroids, you need a specialized mission. One proposal is the Near Earth Asteroid Camera, or NEOCam because it’d be much better to have a telescope that was slightly colder than the 73 K WISE is with coolant, and you can do that by getting away from the Earth. and so the NEOcam telescope is designed to go a million and a half kilometers from the Earth and therefore it would be quite cold, about 35 K and at that temperature, it can operate longer into the infrared and do a very sensitive survey for asteroids.

NEOCam is just one idea. There’s also the Sentinel proposal from B612 Foundation. It’s also an infrared survey and it would go into an orbit like Venus’ orbit, so it would be hundreds of millions of km away from Earth, but not orbiting around Venus, because that would be too hot as well and then with an infrared telescope, it would survey for asteroids.

NEOCam and Sentinel would operate for years, scanning the sky in the infrared to find all of the really hazardous asteroids. You wouldn’t be able to necessarily find the ones the size of the one that hit Chelyabinsk, and so that broke some windows, but it didn’t kill people, didn’t knock buildings down. So that’s definitely a hazard, but not the city destroying hazard that a 100 meter diameter asteroid would be.

We live in a cosmic shooting gallery. Rocks from space impact the Earth all the time, our next dangerous asteroid is out there, somewhere. Let’s build a space-based infrared survey mission so we can find it, before it finds us.

Dr. Andrea Ghez has spent much of her career studying the region right around the center of the Milky Way, including its supermassive black hole. In fact, she helped discover it in the first place. Dr. Ghez speaks about this amazing and dynamic region.

“Hi, I’m Dr. Andrea Ghez, and I’m a professor of physics and astronomy at UCLA. I study the center of our galaxy. The original objective was to figure out if there’s a supermassive black hole there, and in doing this, we’ve actually uncovered more questions than answers.”

What are you looking for at the center of the galaxy?

“We are tremendously privileged to be able to study the center of the galaxy, and have this exquisite laboratory to play with, to get insight into the fundamental physics of black holes, and also their astrophysical role in the formation and evolution of galaxies. You can also ask what kinds of phenomena do you expect to see around a black hole, and we have a lot of predictions about our thoughts about how galaxies form and evolve, and our ideas suggest that there’s a feedback between the galaxy and the black hole. But many of these models predict things that we simply don’t see, which again provides yet another playground.”

What’s it like around the supermassive black hole at the center of the galaxy?

“If you could get into a spaceship and get right down to the black hole, it would be a very busy place. Stars would be zooming around, like the sun, but you’d have a very busy day. You wouldn’t survive – I guess that would be another problem! You’d get torn apart. It’s just a very extreme place. The analogy that often gets made with the center of the galaxy is that it’s like the urban downtown, and we live out in the suburbs, so we live in a very calm place whereas the center of the galaxy is a a very extreme place, in almost every way you can describe an environment.”

What are some of the discoveries?

“The observations at the center of the Milky Way have taught us that one, it’s really normal to have a black hole at the center of the galaxy. I mean, our galaxy is completely ordinary, garden-variety, nothing-special-about-us, so if we have one, presumably every galaxy harbors a supermassive black hole at it’s center. We’ve also learned that the idea that a supermassive black hole should be surrounded by a very dense concentration of very old stars is not true. And that prediction is often used in other galaxies to find their black holes, because we can’t do the kinds of experiments we’ve done at the center of our own – that you look for this concentration of light, but in our galaxy we’re not seeing that, so you have a case where’s there’s absolutely clearly a supermassive black hole, yet you don’t see this collection of old stars. That’s a puzzle.

“Another puzzle that we’ve found that’s illuminating our ideas about other galaxies is that people predicted that you shouldn’t see young stars being formed near a black hole. In fact, in the early 1980’s, when people recognized that there were young stars found in the vicinity of a black hole, that was used to argue that perhaps you couldn’t possibly have a black hole because of these young stars. And yet again, we have a supermassive black hole – we know it, and those young stars are still exist, and we’ve even found stars even closer. And it’s the tidal forces that make it even more difficult to understand why the young stars should be there. The tidal forces pull the gases apart, and for star formation, you need a very fragile balls of gas and dust to collapse, so something’s amiss.”

How might those young stars get formed?

“There are so many ideas about how young stars could form at the center of the galaxy, but the one that has the most support is the idea that, at the time that these stars were being formed, that there was a much denser concentration of gas than there is today, and in that denser concentration you can get the collapse of those little clouds. We think that because as we continue to study the orbits of those stars, and what we’ve seen is that those orbits outside a certain distance start to fall into an ordered plane, like the planets orbiting the sun. We see a substantial fraction of them having a common orbital plane, and that looks very reminiscent to the solar system. The same way the planets formed out of a gas disc in the early days, that’s the same idea that is being invoked for these young stars, on a very different scale.”

Out here in the Milky Way’s suburbs, stellar collisions are unheard of. But there are places in the galaxy where stars whiz past each other, and collisions can happen. When stars collide, it’s a catastrophic event, and the stellar wreckage is visible half a galaxy away.

Continue reading “Astronomy Cast Ep. 332: Stellar Collisions”

Our civilization will need more power in the future. Count on it. The ways we use power today: for lighting, transportation, food distribution and even entertainment would have sounded hilarious and far fetched to our ancestors.

As our technology improves, our demand for power will increase. I have no idea what we’ll use it for, but I guarantee we’ll want it. Perhaps we’ll clean up the oceans, reverse global warming, turn iron into gold, or any number of activities that take massive amounts of energy. Fossil fuels won’t deliver, and they come with some undesirable side effects. Nuclear fuels will only provide so much power until they run out.

We need the ultimate in energy resources. We’ll want to harness the entire power of our star. The Soviet astronomer Nikolai Kardashev predicted that a future civilization might eventually harness the power of an entire planet. He called this a Type I civilization. A Type II would harness the entire energy output of a star. And a Type III civilization would utilize the power of their entire galaxy. So let’s consider a Type II civilization.

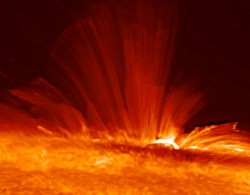

What would it actually take to harness 100% of the energy from a star? We’d need to construct a Dyson Sphere or Cloud and collect all the solar energy that emanates from it. But could we do better? Could we extract material directly from a star?

You bet, it’s the future!

This is an idea known as “stellar lifting”. Stealing hydrogen fuel from the Sun and using it for our futuristic energy needs. In fact, the Sun’s already doing it… poorly. Stars generate powerful magnetic fields. They twist and turn across the surface of the star, and eject hydrogen into space. But it’s just a trickle of material. To truly harness the power of the Sun, we need to get at that store of hydrogen, and speed up the extraction process.

There are a few techniques that might work. You can use lasers to heat up portions of the surface, and increase the volume of the solar wind. You could use powerful magnetic fields to carry plasma away from the Sun’s poles into space.Which ever way it happens, once we’ve got all that hydrogen. How do we use it to get energy? We could combine it with oxygen and release energy via combustion, or we could use it in our space reactors and generate power from fusion.

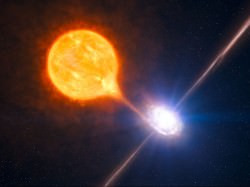

But the most efficient way is to feed it to a black hole and extract its angular momentum. A highly advanced civilization could siphon material directly from a star and send it onto the ergosphere of a rapidly spinning pet black hole.

Here’s Dr. Mark Morris, a Professor of Astronomy at UCLA. He’ll explain:

“There is this region, called the ergosphere between the event horizon and another boundary, outside. The ergosphere is a very interesting region outside the event horizon in which a variety of interesting effects can occur. For example, if we had a black hole at our disposal, we could extract energy from spinning black holes by throwing things into the ergosphere and grabbing whatever comes out at even higher speeds.”

This is known as the Penrose process, first identified by Roger Penrose in 1969. It’s theoretically possible to retrieve 29% of the energy in a rotating black hole. Unfortunately, you also slow it down. Eventually the black hole stops spinning, and you can’t get any more energy out of it. But then it might also be possible to extract energy from Hawking radiation; the slow evaporation of black holes over eons. Of course, it’s tricky business.

Dr. Morris continues, “There’s no inherent limitation except for the various problems working in the vicinity of a massive black hole. One can’t be anywhere near a black hole that’s actively accreting matter because the high flux of energetic particles and gamma rays. So it’s a hostile environment near most realistic black holes, so let me just say that it won’t be any time soon as far as our civilization is concerned. But maybe Type III civilizations so far beyond us that it exceeds our imagination won’t have any problem.”

A Type 3 civilization would be so advanced, with such a demand for energy, they could be extracting the material from all the stars in the galaxy and feeding it directly to black holes to harvest energy. Feeding black holes to other black holes to spin them back up again.

It’s an incomprehensible feat of galactic engineering. And yet, it’s one potential outcome of our voracious demand for energy.

Host: Fraser Cain

Guests: Brian Koberlein, Morgan Rehnberg, David Dickinson, Jason Major, Nicole Gugliucci

Continue reading “Weekly Space Hangout – January 31, 2014: No Black Holes?!?”