Comets can spend billions of years out in the Oort Cloud, and then a few brief moments of terror orbiting the Sun. These are the sun grazers. Some survive their journey, and flare up to become the brightest comets in history. Others won’t survive their first, and only encounter with the Sun.

Continue reading “Astronomy Cast 324: Sun Grazers”

How Does a Star Form?

We owe our entire existence to the Sun. Well, it and the other stars that came before. As they died, they donated the heavier elements we need for life. But how did they form?

Stars begin as vast clouds of cold molecular hydrogen and helium left over from the Big Bang. These vast clouds can be hundreds of light years across and contain the raw material for thousands or even millions of times the mass of our Sun. In addition to the hydrogen, these clouds are seeded with heavier elements from the stars that lived and died long ago. They’re held in balance between their inward force of gravity and the outward pressure of the molecules. Eventually some kick overcomes this balance and causes the cloud to begin collapsing.

That kick could come from a nearby supernova explosion, collision with another gas cloud, or the pressure wave of a galaxy’s spiral arms passing through the region. As this cloud collapses, it breaks into smaller and smaller clumps, until there are knots with roughly the mass of a star. As these regions heat up, they prevent further material from falling inward.

At the center of these clumps, the material begins to increase in heat and density. When the outward pressure balances against the force of gravity pulling it in, a protostar is formed. What happens next depends on the amount of material.

Some objects don’t accumulate enough mass for stellar ignition and become brown dwarfs – substellar objects not unlike a really big Jupiter, which slowly cool down over billions of years.

If a star has enough material, it can generate enough pressure and temperature at its core to begin deuterium fusion – a heavier isotope of hydrogen. This slows the collapse and prepares the star to enter the true main sequence phase. This is the stage that our own Sun is in, and begins when hydrogen fusion begins.

If a protostar contains the mass of our Sun, or less, it undergoes a proton-proton chain reaction to convert hydrogen to helium. But if the star has about 1.3 times the mass of the Sun, it undergoes a carbon-nitrogen-oxygen cycle to convert hydrogen to helium. How long this newly formed star will last depends on its mass and how quickly it consumes hydrogen. Small red dwarf stars can last hundreds of billions of years, while large supergiants can consume their hydrogen within a few million years and detonate as supernovae. But how do stars explode and seed their elements around the Universe? That’s another episode.

We have written many articles about star formation on Universe Today. Here’s an article about star formation in the Large Magellanic Cloud, and here’s another about star formation in NGC 3576.

Want more information on stars? Here’s Hubblesite’s News Releases about Stars, and more information from NASA’s imagine the Universe.

We have recorded several episodes of Astronomy Cast about stars. Here are two that you might find helpful: Episode 12: Where Do Baby Stars Come From, and Episode 13: Where Do Stars Go When they Die?

Source: NASA

Virtual Star Party – December 1, 2013 – Dying Comets, Smashing Galaxies and Cosmic Bees

Hosts: Fraser Cain and Scott Lewis

Astronomers: Gary Gonella, Roy Salisbury, Steven Coates, Tom Nathe, Stuart Foreman

Continue reading “Virtual Star Party – December 1, 2013 – Dying Comets, Smashing Galaxies and Cosmic Bees”

What is the Universe Expanding Into?

Come on, admit it, you’ve had this question. “Since astronomers know that the Universe is expanding, what’s it expanding into? What’s outside of the Universe?” Ask any astronomer and you’ll get an unsatisfying answer. We give you the same unsatisfying answer, but really explain it, so your unsatisfaction doesn’t haunt you any more.

The short answer is that this is a nonsense question, the Universe isn’t expanding into anything, it’s just expanding.

The definition of the Universe is that it contains everything. If something was outside the Universe, it would also be part of the Universe too. Outside of that? Still Universe. Out side of THAT? Also more Universe. It’s Universe all the way down. But I know you’re going to find that answer unsatisfying, so now I’m going to break your brain.

Either the Universe is infinite, going on forever, or its finite, with a limited volume. In either case, the Universe has no edge. When we imagine the Universe expanding after the Big Bang, we imagine an explosion, with a spray of matter coming from a single point. But this analogy isn’t accurate.

A better analogy is the surface of an expanding balloon. Not the 3 dimensional balloon, just its 2 dimensional surface. If you were an ant crawling around the surface of a huge balloon, and the balloon was your whole universe, you would see the balloon as essentially flat under your feet.

Imagine the balloon is inflating. In every direction you look, other ants are moving away from you. The further they are, the faster away they’re moving. Even though it feels like a flat surface, walk in any direction long enough and you’d return to your starting point.

You might imagine a growing circle and wonder what it’s expanding into. But that’s a nonsense question. There’s no direction you could crawl that would get you outside the surface. Your 2-dimensional ant brain can’t comprehend an expanding 3-dimensional object. There may be a center to the balloon, but there’s no center to the surface. Just a shape that extends in all directions and wraps in upon itself. And yet, your journey to make one lap around the balloon takes longer and longer as the balloon gets more inflated.

To better understand how this relates to our Universe, we need to scale things up by one dimension, from a 2-d surface embedded in a 3-d world, to a 3-d volume embedded within a 4-d universe. Astronomers think that if you travel in any direction far enough, you’ll return to your starting position. If you could stare far enough into space, you would be looking at the back of your own head.

And so, as the Universe expands, it would take you longer and longer to lap the Universe and return to your starting position. But there’s no direction you could travel in that would take you outside or “off” of the Universe. Even if you could move faster than the speed of light, you’d just return to your starting position more quickly. We see other galaxies moving away from us in all directions just as our ant would see other ants moving away on the surface of the balloon.

A great analogy comes from my Astronomy Cast co-host, Dr. Pamela Gay. Instead of an explosion, imagine the expanding Universe is like a loaf of raisin bread rising in the oven. From the perspective of any raisin, all the other raisins are moving away in all directions. But unlike a loaf of raisin bread, you could travel in any one direction within the bread and eventually return to your starting raisin.

Remember that our entire comprehension is based on 3-dimensions. If we were 4-dimensional creatures, this would make much more sense. For a much deeper explanation, I highly recommend you watch my good friend, Zogg the Alien explain how the Universe has no edge. After watching his videos, you should totally understand the possible topologies of our Universe.

I hope this helps you understand why there’s no answer to “what is the Universe expanding into?” With no edge, it’s not expanding into anything, it’s just expanding.

You can also listen to our podcast episode explaining this here –

What is the Universe Expanding Into – Show notes and transcript

Or subscribe to: astronomycast.com/podcast.xml

Astronomy Cast 323: Isotopes

The number of protons defines an element, but the number of neutrons can vary. We call these different flavors of an element isotopes, and use these isotopes to solve some challenging mysteries in physics and astronomy. Some isotopes occur naturally, and others need to be made in nuclear reactors and particle accelerators.

Are There More Grains of Sand Than Stars?

This question comes from Sheldon Grimshaw. “I’ve heard that there are more stars in our Universe than there are grains of sand on all the beaches on Earth. Is this possible?” Awesome question, and a great excuse to do some math.

As we learned in a previous video, there are 100 to 400 billion stars in the Milky Way and more than 100 billion galaxies in the Universe – maybe as many as 500 billion. If you multiply stars by galaxies, at the low end, you get 10 billion billion stars, or 10 sextillion stars in the Universe – a 1 followed by 22 zeros. At the high end, it’s 200 sextillion.

These are mind bogglingly huge numbers. How do they compare to the number of grains of sand on the collective beaches of an entire planet? This type of sand measures about a half millimeter across.

You could put 20 grains of sand packed in side-by-side to make a centimeter. 8000 grains in one cubic centimeter. If you took 10 sextillion grains of sand, put them into a ball, it would have a radius of 10.6 kilometers. And for the high end of our estimate, 200 sextillion, it would be 72 kilometers across. If we had a sphere bigger than the Earth, it would be an easy answer, but no such luck. This might be close.

So, is there that much sand on all the beaches, everywhere, on this planet? You’d need to estimate the average volume of a sandy beach and the average amount of the world’s coastlines which are beaches.

I’m going to follow the estimates and calculations made by Dr. Jason Marshall, aka, the Math Dude. According to Jason, there about 700 trillion cubic meters of beach of Earth, and that works out to around 5 sextillion grains of sand.

Jason reminds us that his math is a rough estimate, and he could be off by a factor of 2 either way. So it could be 2.5 sextillion or there could be 10 sextillion grains of sand on all the world’s beaches.

So, if the low end estimate for the number of stars matches the high end estimate for the number of grains of sand, it’s the same. But more likely, there are 5 to 10 times more stars than there are grains of sand on all the world’s beaches.

So, there’s your answer, Sheldon. For some “back of the napkin” math we can guess that there are more stars in our Universe than there are grains of sand on all the beaches of Earth.

Oh, one more thing. Instead of grains of sand, what about atoms? How big is 10 sextillion atoms? How huge would something with that massive quantity of anything be? Pretty gigantic. Well, relatively at least. 10 sextillion of anything does sound like a whole lot.

If you were to make a pile of that many atoms… guess how big it would be. It’d be about…. (gesture big then gesture small) 4 times smaller than a dust mite. Which means, a single grain of sand has more atoms than there are stars in the Universe.

Virtual Star Party – November 24, 2013: Comets and More!

Hosts: Fraser Cain, Scott Lewis

Astronomers: Bill McLaughlin, David Dickinson, Tom Nathe, Mike Phillips

Viewing: M103, Cocoon Nebula, Comet Lovejoy, more to come!

We hold the Virtual Star Party every Sunday night as a live Google+ Hangout on Air. We begin the show when it gets dark on the West Coast. If you want to get a notification, make sure you circle the Virtual Star Party on Google+. You can watch on our YouTube channel or here on Universe Today.

Weekly Space Hangout – November 22, 2013: MAVEN, Minotaur, Comet Nevski

Host: Fraser Cain

Guests: Nancy Atkinson, Amy Shira Teitel, David Dickinson

Continue reading “Weekly Space Hangout – November 22, 2013: MAVEN, Minotaur, Comet Nevski”

What is a Pulsar?

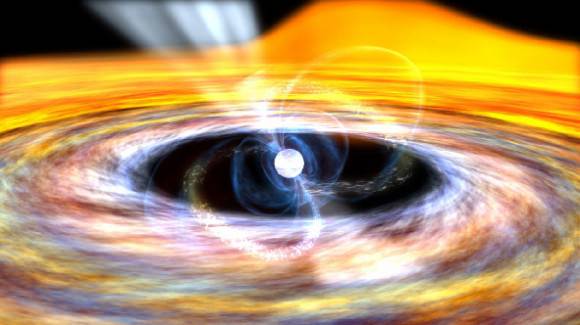

They are what is known as the “lighthouses” of the universe – rotating neutron stars that emit a focused beam of electromagnetic radiation that is only visible if you’re standing in it’s path. Known as pulsars, these stellar relics get their name because of the way their emissions appear to be “pulsating” out into space.

Not only are these ancient stellar objects very fascinating and awesome to behold, they are very useful to astronomers as well. This is due to the fact that they have regular rotational periods, which produces a very precise internal in its pulses – ranging from milliseconds to seconds.

Description:

Pulsars are types of neutron stars; the dead relics of massive stars. What sets pulsars apart from regular neutron stars is that they’re highly magnetized, and rotating at enormous speeds. Astronomers detect them by the radio pulses they emit at regular intervals.

Formation:

The formation of a pulsar is very similar to the creation of a neutron star. When a massive star with 4 to 8 times the mass of our Sun dies, it detonates as a supernova. The outer layers are blasted off into space, and the inner core contracts down with its gravity. The gravitational pressure is so strong that it overcomes the bonds that keep atoms apart.

Electrons and protons are crushed together by gravity to form neutrons. The gravity on the surface of a neutron star is about 2 x 1011 the force of gravity on Earth. So, the most massive stars detonate as supernovae, and can explode or collapse into black holes. If they’re less massive, like our Sun, they blast away their outer layers and then slowly cool down as white dwarfs.

But for stars between 1.4 and 3.2 times the mass of the Sun, they may still become supernovae, but they just don’t have enough mass to make a black hole. These medium mass objects end their lives as neutron stars, and some of these can become pulsars or magnetars. When these stars collapse, they maintain their angular momentum.

But with a much smaller size, their rotational speed increases dramatically, spinning many times a second. This relatively tiny, super dense object, emits a powerful blast of radiation along its magnetic field lines, although this beam of radiation doesn’t necessarily line up with it’s axis of rotation. So, pulsars are simply rotating neutron stars.

And so, from here on Earth, when astronomers detect an intense beam of radio emissions several times a second, as it rotates around like a lighthouse beam – this is a pulsar.

History:

The first pulsar was discovered in 1967 by Jocelyn Bell Burnell and Antony Hewis, and it surprised the scientific community by the regular radio emissions it transmitted. They detected a mysterious radio emission coming from a fixed point in the sky that peaked every 1.33 seconds. These emissions were so regular that some astronomers thought it might be evidence of communications from an intelligent civilization.

Although Burnell and Hewis were certain it had a natural origin, they named it LGM-1, which stands for “little green men”, and subsequent discoveries have helped astronomers discover the true nature of these strange objects.

Astronomers theorized that they were rapidly rotating neutron stars, and this was further supported by the discovery of a pulsar with a very short period (33-millisecond) in the Crab nebula. There have been a total of 1600 found so far, and the fastest discovered emits 716 pulses a second.

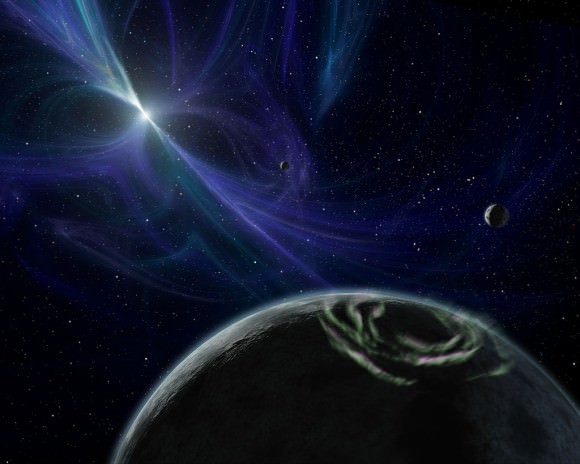

Later on, pulsars were found in binary systems, which helped to confirm Einstein’s theory of general relativity. And in 1982, a pulsar was found with a rotation period of just 1.6 microseconds. In fact, the first extrasolar planets ever discovered were found orbiting a pulsar – of course, it wouldn’t be a very habitable place.

Interesting Facts:

When a pulsar first forms, it has the most energy and fastest rotational speed. As it releases electromagnetic power through its beams, it gradually slows down. Within 10 to 100 million years, it slows to the point that its beams shut off and the pulsar becomes quiet.

When they are active, they spin with such uncanny regularity that they’re used as timers by astronomers. In fact, it is said that certain types of pulsars rival atomic clocks in their accuracy in keeping time.

Pulsars also help us search for gravitational waves, probe the interstellar medium, and even find extrasolar planets in orbit. In fact, the first extrasolar planets were discovered around a pulsar in 1992, when astronomers Aleksander Wolszczan and Dale Frail announced the discovery of a multi-planet planetary system around PSR B1257+12 – a millisecond pulsar now known to have two extrasolar planets.

It has even been proposed that spacecraft could use them as beacons to help navigate around the Solar System. On NASA’s Voyager spacecraft, there are maps that show the direction of the Sun to 14 pulsars in our region. If aliens wanted to find our home planet, they couldn’t ask for a more accurate map.

We have written many articles about stars here on Universe Today. Here’s an article about a newly discovered gamma ray pulsar, and here’s an article about how millisecond pulsars spin so fast.

If you’d like more information on stars, check out Hubblesite’s News Releases about Stars, and here’s the stars and galaxies homepage.

We have recorded several episodes of Astronomy Cast about stars. Here are two that you might find helpful: Episode 12: Where Do Baby Stars Come From, and Episode 13: Where Do Stars Go When they Die?

What Is The Evidence For The Big Bang?

Almost all astronomers agree on the theory of the Big Bang, that the entire Universe is spreading apart, with distant galaxies speeding away from us in all directions. Run the clock backwards to 13.8 billion years ago, and everything in the Cosmos started out as a single point in space. In an instant, everything expanded outward from that location, forming the energy, atoms and eventually the stars and galaxies we see today. But to call this concept merely a theory is to misjudge the overwhelming amount of evidence.

There are separate lines of evidence, each of which independently points towards this as the origin story for our Universe. The first came with the amazing discovery that almost all galaxies are moving away from us.

In 1912, Vesto Slipher calculated the speed and direction of “spiral nebulae” by measuring the change in the wavelengths of light coming from them. He realized that most of them were moving away from us. We now know these objects are galaxies, but a century ago astronomers thought these vast collections of stars might actually be within the Milky Way.

In 1924, Edwin Hubble figured out that these galaxies are actually outside the Milky Way. He observed a special type of variable star that has a direct relationship between its energy output and the time it takes to pulse in brightness. By finding these variable stars in other galaxies, he was able to calculate how far away they were. Hubble discovered that all these galaxies are outside our own Milky Way, millions of light-years away.

So, if these galaxies are far, far away, and moving quickly away from us, this suggests that the entire Universe must have been located in a single point billions of years ago. The second line of evidence came from the abundance of elements we see around us.

In the earliest moments after the Big Bang, there was nothing more than hydrogen compressed into a tiny volume, with crazy high heat and pressure. The entire Universe was acting like the core of a star, fusing hydrogen into helium and other elements.

This is known as Big Bang Nucleosynthesis. As astronomers look out into the Universe and measure the ratios of hydrogen, helium and other trace elements, they exactly match what you would expect to find if the entire Universe was once a really big star.

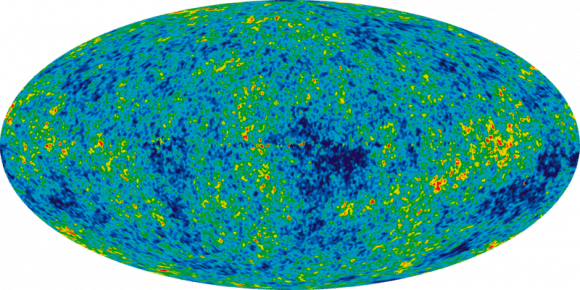

Line of evidence number 3: cosmic microwave background radiation. In the 1960s, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson were experimenting with a 6-meter radio telescope, and discovered a background radio emission that was coming from every direction in the sky – day or night. From what they could tell, the entire sky measured a few degrees above absolute zero.

Theories predicted that after a Big Bang, there would have been a tremendous release of radiation. And now, billions of years later, this radiation would be moving so fast away from us that the wavelength of this radiation would have been shifted from visible light to the microwave background radiation we see today.

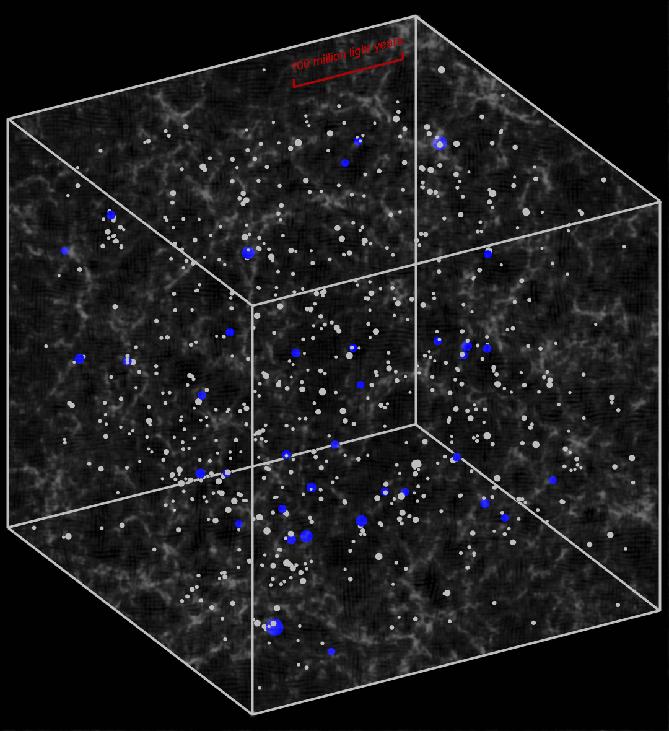

The final line of evidence is the formation of galaxies and the large scale structure of the cosmos. About 10,000 years after the Big Bang, the Universe cooled to the point that the gravitational attraction of matter was the dominant form of energy density in the Universe. This mass was able to collect together into the first stars, galaxies and eventually the large scale structures we see across the Universe today.

These are known as the 4 pillars of the Big Bang Theory. Four independent lines of evidence that build up one of the most influential and well-supported theories in all of cosmology. But there are more lines of evidence. There are fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background radiation, we don’t see any stars older than 13.8 billion years, the discoveries of dark matter and dark energy, along with how the light curves from distant supernovae.

So, even though it’s a theory, we should regard it the same way that we regard gravity, evolution and general relativity. We have a pretty good idea of what’s going on, and we’ve come up with a good way to understand and explain it. As time progresses we’ll come up with more inventive experiments to throw at. We’ll refine our understanding and the theory that goes along with it.

Most importantly, we can have confidence when talking about what we know about the early stages of our magnificent Universe and why we understand it to be true.