[/caption]

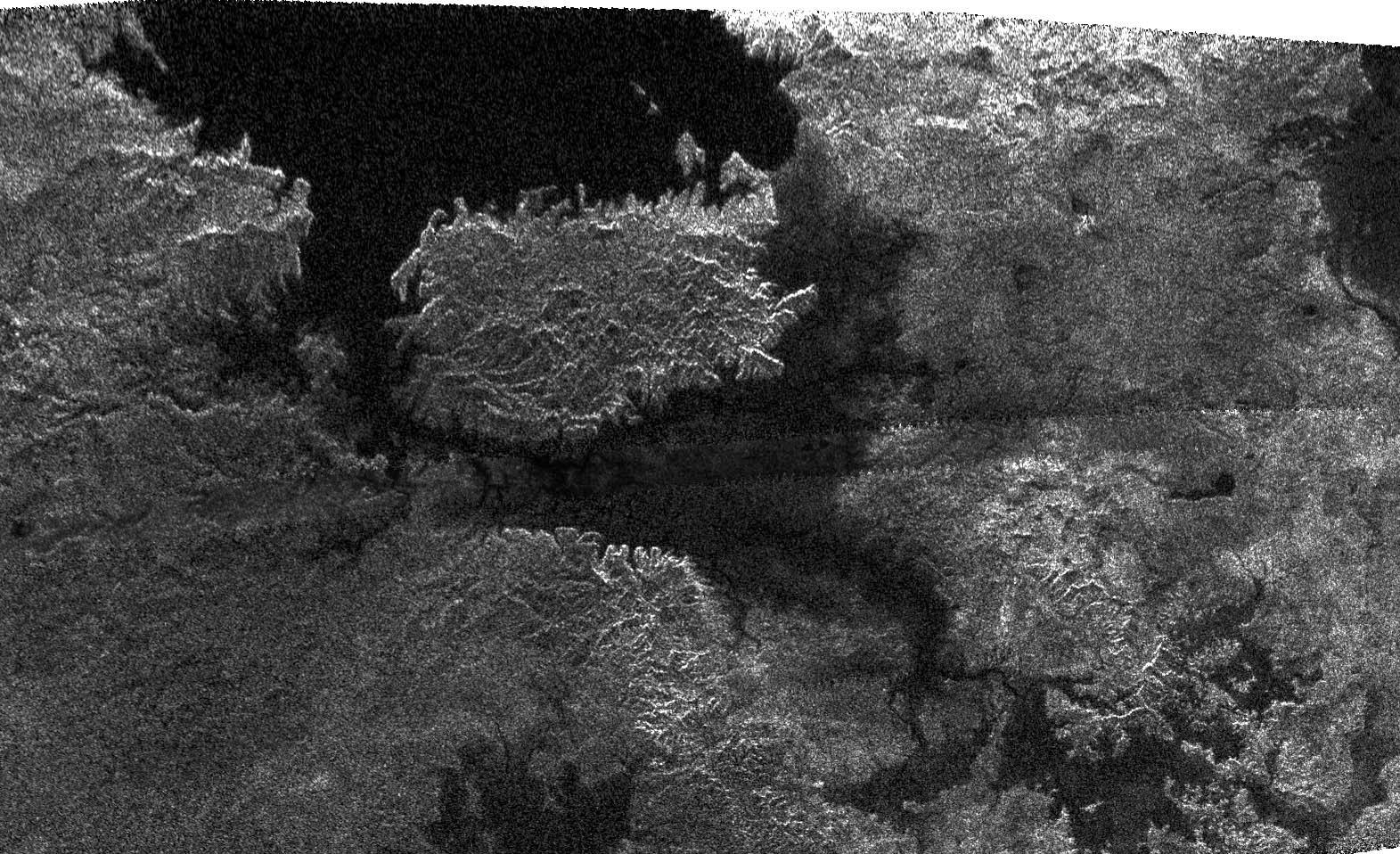

Even though there are lakes and rivers of liquid hydrocarbons on the surface of Saturn’s moon Titan, the rains that feed them may come few and far between. According to data gathered by NASA’s Cassini mission, parts of Titan might not see rain for more than 1,000 years.

And according to Dr. Ralph Lorenz, from the John Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (JHUALP), a new mission to Titan is exactly what’s needed to get to the bottom of this.

Rain on Titan?! It sounds bizarre, but scientists have observed a complex cycle of liquid on Titan, with lakes and rivers, clouds, and the rain that must feed them. But on Titan, where surface temperatures plunge to -179C, we’re not talking about water. The whole hydrological cycle runs with methane: methane lakes, methane rivers, and methane rain.

And it appears that the rain on Titan can be extreme, with deep river channels that must have had enormous flows for brief periods. But this rain must also be rare. In all of its observations of Titan, Cassini only spotted two instances of darkened regions that might have indicated rainfall.

In a recent talk at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC), Dr. Lorenz presented his estimates of the Titan rainfall, and the need for a new mission that could study it.

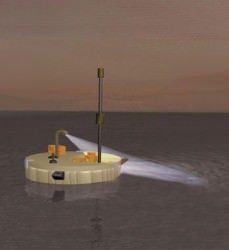

Titan Mare Explorer (TiME)

Dr. Lorenz is one of the scientists involved with the proposed Titan Mare Explorer (TiME) mission; one of three shortlisted missions that might be turned into NASA Discovery missions.

If selected, TiME would travel to the Saturn system, descend through Titan’s thick atmosphere, and land in Ligeia Mara, a large lake on the surface of the moon. It would search for rainstorms on the descent – an extremely unlikely event – and then watch the skies for evidence of rainfall. It would be able to “hear” rain falling directly onto it, and in the liquid around it. TiME would also be equipped with instruments that would let it see cloud formation, rain shafts, and even methane rainbows.

Assuming the rain shafts are 10 km wide, and would be observable at distances of 20 km, the lander should be able to detect rainstorms within a 1200 km2 area. According to Dr. Lorenz:

We might expect a 50% chance for a lander to be rained on directly in a 2500hr mission, but that its camera could observe nearby rainfall an expected ~5 times.

Once in 1,000 years?

While the weather system on Titan is similar to Earth, it probably has some significant differences, which Cassini observations have hinted at. Although there were possible storms seen in 2004, there was a huge gap until 2010. After the “storm”, the surface of Titan was changed with a large darkened area that could indicate saturation of liquid on the surface. These ponds seemed to dry up in future observations.

Estimates indicate that regions near Titan’s poles see rainfall for 10-100 hours every Titan year (30 Earth years). But the drier parts of the moon might not see more than a single rainfall every 1,000 years.

Source: USRA Presentation