[/caption]

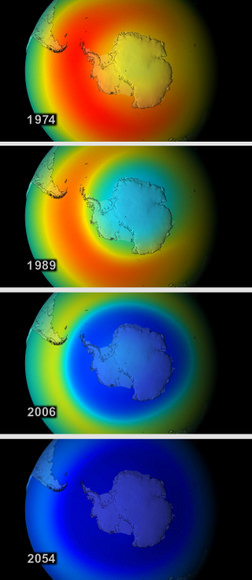

Imagine the year 2065. Two-thirds of Earth’s ozone is gone. The infamous ozone hole over Antarctica is a year-round fixture with a twin over the North Pole. People living in mid-latitude cities like Washington, D.C., get sunburned after five minutes. DNA-mutating UV radiation is up 650 percent, with likely harmful effects on plants, animals and human skin cancer rates.

Such is the world we would have inherited if 193 nations had not agreed to ban ozone-depleting substances, according to atmospheric chemists at NASA, Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency in Bilthoven. The researchers have unveiled new computer simulations this week of a worldwide disaster that humans managed to avoid.

In retrospect, the researchers say, the Montreal Protocol was a “remarkable international agreement that should be studied by those involved with global warming and the attempts to reach international agreement on that topic.”

Ozone is Earth’s natural sunscreen, absorbing and blocking most of the incoming UV radiation from the sun and protecting life from DNA-damaging radiation. The gas is naturally created and replenished by a photochemical reaction in the upper atmosphere where UV rays break oxygen molecules into individual atoms that then recombine into three-part molecules (O3). As it is moved around the globe by upper level winds, ozone is slowly depleted by naturally occurring atmospheric gases. It is a system in natural balance.

But chlorofluorocarbons — invented in 1928 as refrigerants and as inert carriers for chemical sprays — upset that balance. Researchers discovered in the 1970s and 1980s that while CFCs are inert at Earth’s surface, they are quite reactive in the stratosphere (10 to 50 kilometers altitude, or 6 to 31 miles), where roughly 90 percent of the planet’s ozone accumulates. UV radiation causes CFCs and similar bromine compounds in the stratosphere to break up into elemental chlorine and bromine that readily destroy ozone molecules.

In the 1980s, ozone-depleting substances opened a wintertime “hole” over Antarctica and opened the eyes of the world to the effects of human activity on the atmosphere. In January 1989, the Montreal Protocol went into force, the first-ever international agreement on regulation of chemical pollutants.

In the new study, published online in the journal Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, Goddard scientist Paul Newman and his team simulated “what might have been” if chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and similar chemicals were not banned. The simulation used a comprehensive model that included atmospheric chemical effects, wind changes, and radiation changes. The “World avoided” video can be viewed here in Quicktime (for more formats, go here).

By the simulated year 2020, 17 percent of all ozone is depleted globally. An ozone hole starts to form each year over the Arctic, which was once a place of prodigious ozone levels.

By 2040, global ozone concentrations fall below the same levels that currently comprise the “hole” over Antarctica. The UV index in mid-latitude cities reaches 15 around noon on a clear summer day, giving a perceptible sunburn in about 10 minutes. Over Antarctica, the ozone hole becomes a year-round fixture.

By the end of the model run in 2065, global ozone drops 67 percent compared to 1970s levels. The intensity of UV radiation at Earth’s surface doubles; at certain shorter wavelengths, intensity rises by as much as 10,000 times. Skin cancer-causing radiation soars.

“Our world avoided calculation goes a little beyond what I thought would happen,” said Goddard scientist and study co-author Richard Stolarski, who was among the pioneers of atmospheric ozone chemistry in the 1970s. “The quantities may not be absolutely correct, but the basic results clearly indicate what could have happened to the atmosphere.”

“We simulated a world avoided,” added Newman, “and it’s a world we should be glad we avoided.”

As it is, production of ozone-depleting substances was mostly halted about 15 years ago, though their abundance is only beginning to decline because the chemicals can reside in the atmosphere for 50 to 100 years. The peak abundance of CFCs in the atmosphere occurred around 2000, and has decreased by roughly 4 percent to date. Stratospheric ozone was depleted by 5 to 6 percent at middle latitudes, but has somewhat rebounded in recent years.