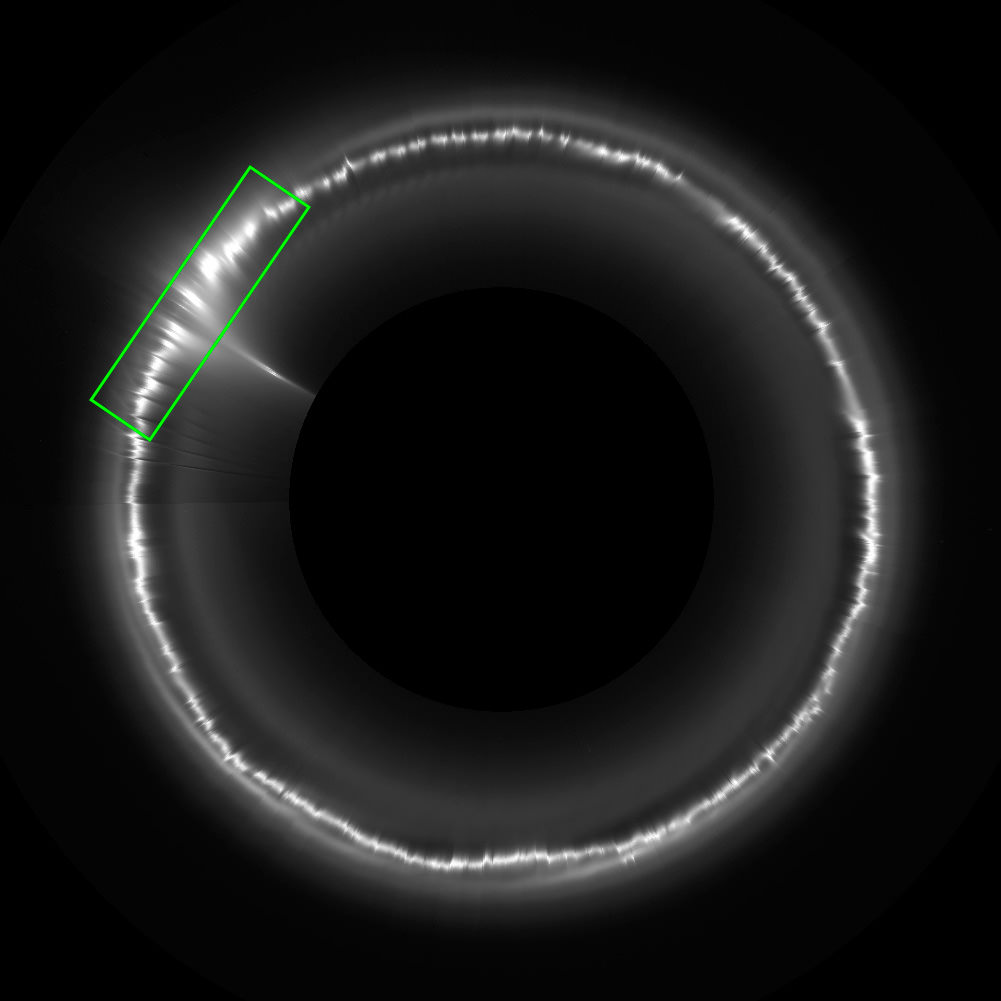

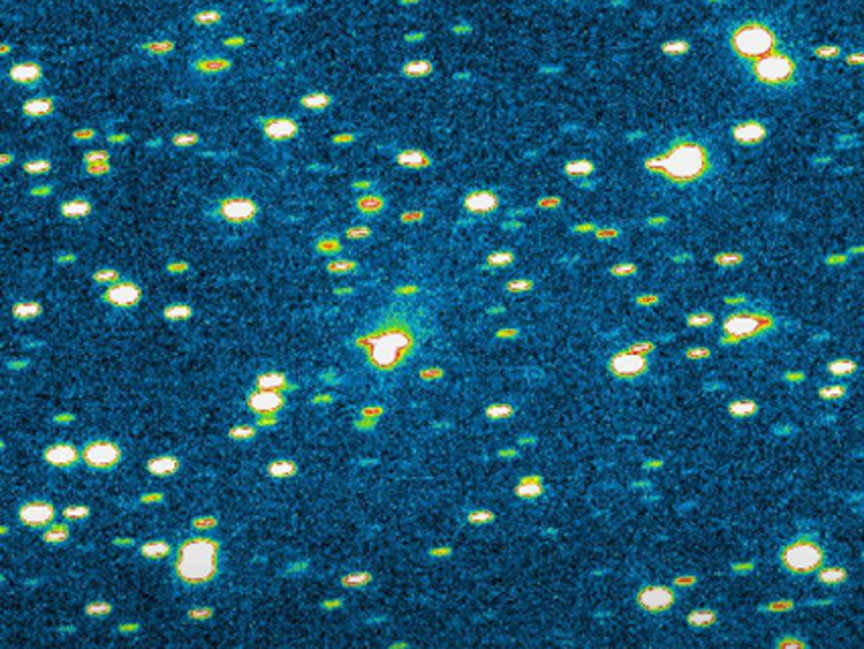

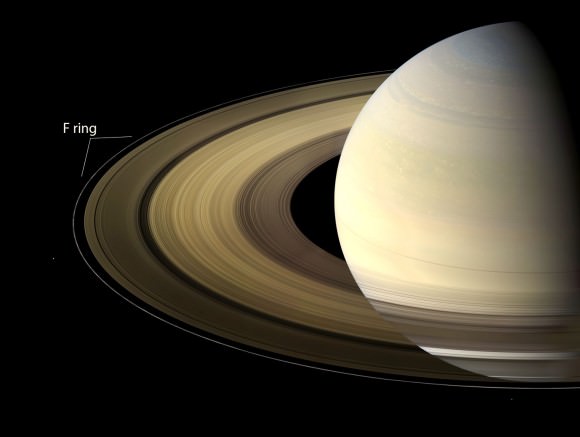

Nothing stands still. Everything evolves. So why shouldn’t Saturn’s kookie, clumpy F ring put on a new face from time to time?

A recent NASA-funded study compared the F ring’s appearance in six years of observations by the Cassini mission to its appearance during the Saturn flybys of NASA’s Voyager mission, 30 years earlier.

While the F ring has always displayed clumps of icy matter, the study team found that the number of bright clumps has nose-dived since the Voyager space probes saw them routinely during their brief flybys 30 years ago. Cassini spied only two of the features during a six-year period.

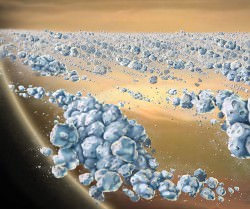

Scientists have long suspected that moonlets up to 3 miles (5 km) wide hiding in the F ring are responsible for its uneven texture. Kinks and knots appear and disappear within months compared to the years of observation needed changes in many of the other rings.

“Saturn’s F ring looks fundamentally different from the time of Voyager to the Cassini era,” said Robert French of the SETI Institute in Mountain View, California, who led the study along with SETI Principal Investigator Mark Showalter. “It makes for an irresistible mystery for us to investigate.”

Because the moonlets lie close to the ring and cross through it every orbit, the research team hypothesizes that the clumps are created when they crash into and pulverize smaller ring particles during each pass. They suspect that the decline in the number of exceptionally bright kinks and the clumps echoes a decline in the number of moonlets available to do the job.

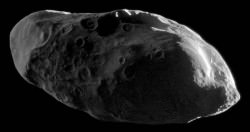

So what happened between Voyager and Cassini? Blame it on Prometheus. The F ring circles Saturn at a delicate point called the Roche Limit. Any moons orbiting closer than the limit would be torn apart by Saturn’s gravitational force.

“Material at this distance from Saturn can’t decide whether it wants to remain as a ring or coalesce to form a moon,” said French. “Prometheus orbits just inside the F ring, and adds to the pandemonium by stirring up the ring particles, sometimes leading to the creation of moonlets, and sometimes leading to their destruction.”

Every 17 years the orbit of Prometheus aligns with the orbit of the F ring in a way that enhances its gravitational influence. The researchers think the alignment spurs the creation of lots of extra moonlets which then go crashing into the ring, creating bright clumps of material as they smash themselves to bits against other ring material.

Sounds like a terrifying version of carnival bumper cars. In this scenario, the number of moonlets would gradually drop off until another favorable Prometheus alignment.

The Voyagers encounters with Saturn occurred a few years after the 1975 alignment between Prometheus and the F ring, and Cassini was present for the 2009 alignment. Assuming Prometheus has been “working” to build new moons since 2009, we should see the F ring light up once again with bright clumps in the next couple years.

Cassini will be watching.