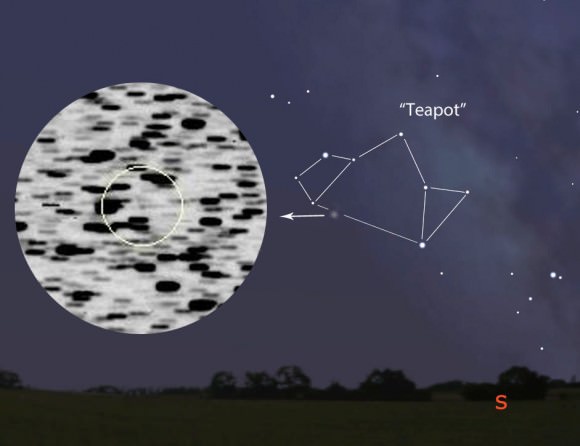

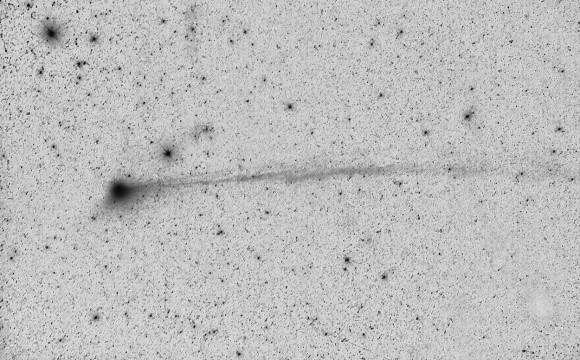

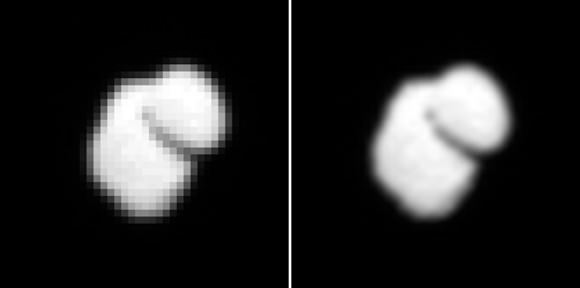

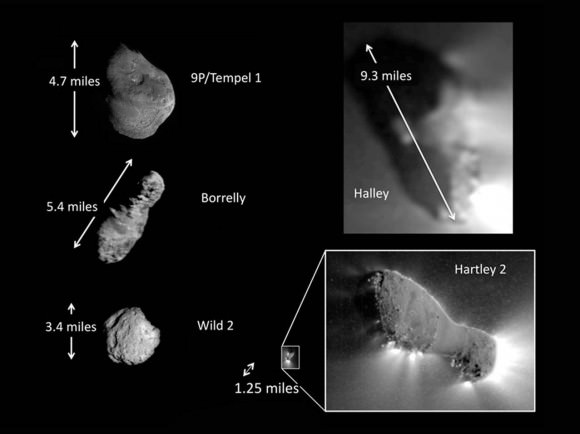

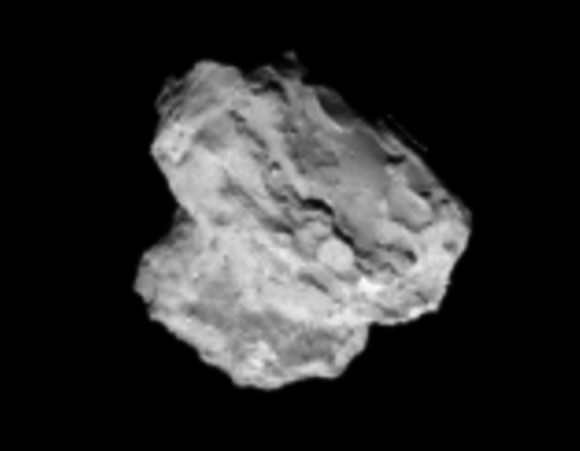

We’re finally getting to know the icy nucleus behind comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. For all the wonder that comets evoke, we on Earth never see directly what whips up the coma and tail. Even professional telescopes can’t burrow through the dust and vapor cloaking the nucleus to distinguish the clear outline of a comet’s heart. The only way to see one is to fly a camera there.

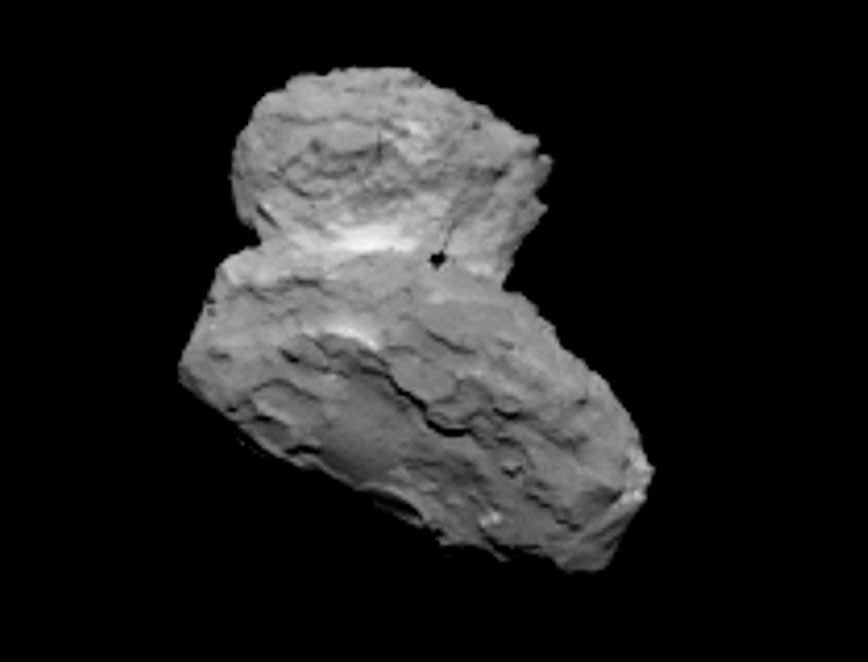

Rosetta took 10 years to reach 67P/C-G, a craggy, boot-shaped body that resembles an asteroid in appearance but with key differences. Asteroids shown in close up photos often display typical bowl-shaped impact craters. From the photos to date, 67P/C-G’s ‘craters’ look shallow and flat in comparison. Were they impacts smoothed by ice flows over time? Did some of the dust and vapor spewed by the comet settle back on the surface to partially bury and soften the landscape?

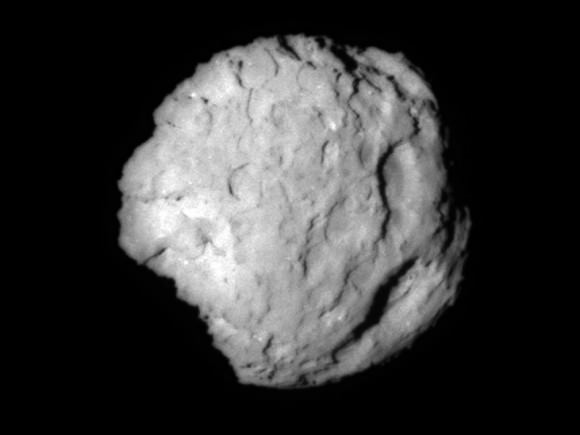

While 67P is doubtless its own comet, it does share certain similarities with Comet 81P/Wild including at least a few crater-like depressions seen during NASA’s Stardust mission. In January 2004, the spacecraft gathered photos, measurements and dust samples during its brief flyby of the nucleus. Photos reveal pinnacles, flat-bottomed depressions and bright plumes or jets of vaporizing ice.

In a 2004 paper by Donald Brownlee and team, the group experimentally reproduced the flat-floored craters by firing projectiles into resin-coated sand baked a bit to make it cohere. Their results suggest the craters formed from impacts in loosely compacted material under the low-gravity conditions typical of small objects like comets. To quote the paper: “Most disrupted material stayed inside the cavity and formed a flat-floored deposit and steep cliffs formed the rim.” Icy materials mixed with dust may have also played a role in their appearance and other crater-like depressions called pit-halos.

Speculation isn’t science, so I’ll stop here. So much more data will be streaming in soon, we’ll have our hands full. On Wednesday, August 6th, Rosetta will enter orbit around the nucleus and begin detailed studies that will continue through December 2015. Studying the new pictures now arriving daily, I’m struck by the dual nature of comets. We see an ancient landscape and yet one that looks strangely contemporary as the sun vaporizes ice, reworking the terrain like a child molding clay.