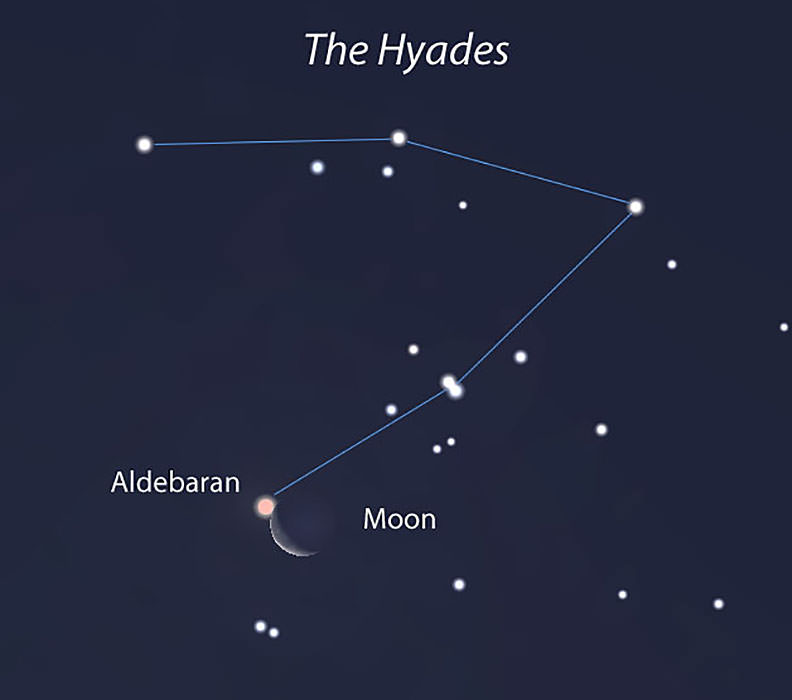

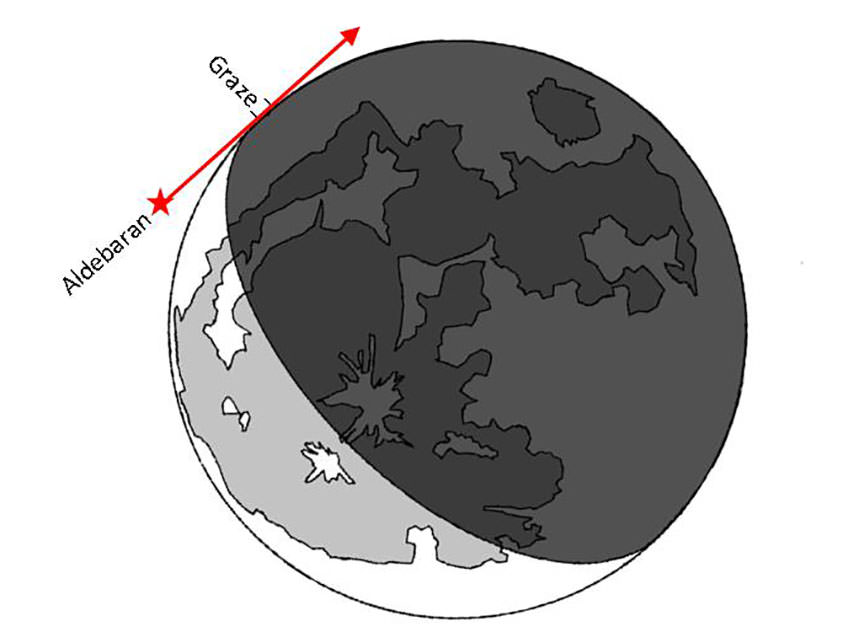

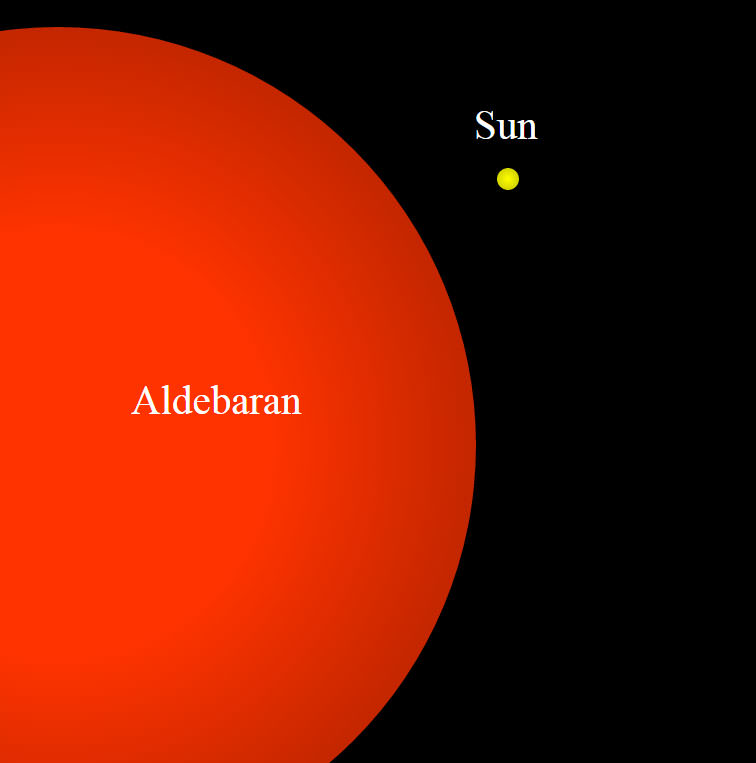

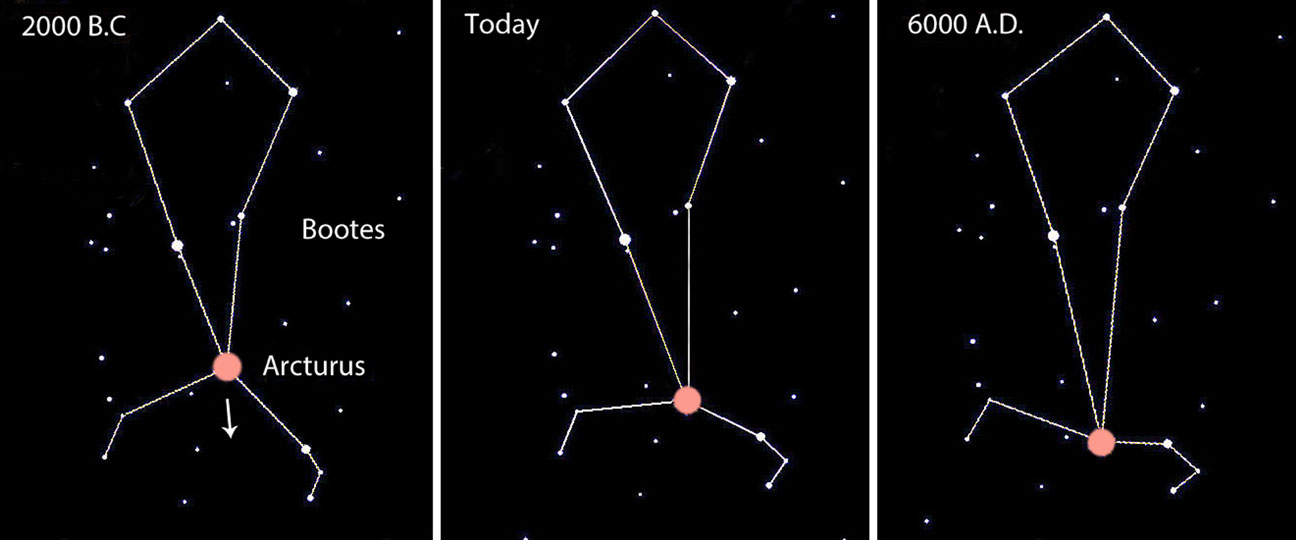

You go out and look at the stars year after year and never see any of them get up and walk away from their constellations. Take a time machine back to the days of Plato and Socrates and only careful viewing would reveal that just three of the sky’s naked eye stars had budged: Arcturus, Sirius and Aldebaran. And then only a little. Their motion was discovered by Edmund Halley in 1718 when he compared the stars’ positions then to their positions noted by the ancient Greek astronomers. In all three cases, the stars had moved “above a half a degree more Southerly at this time than the Antients reckoned them.”

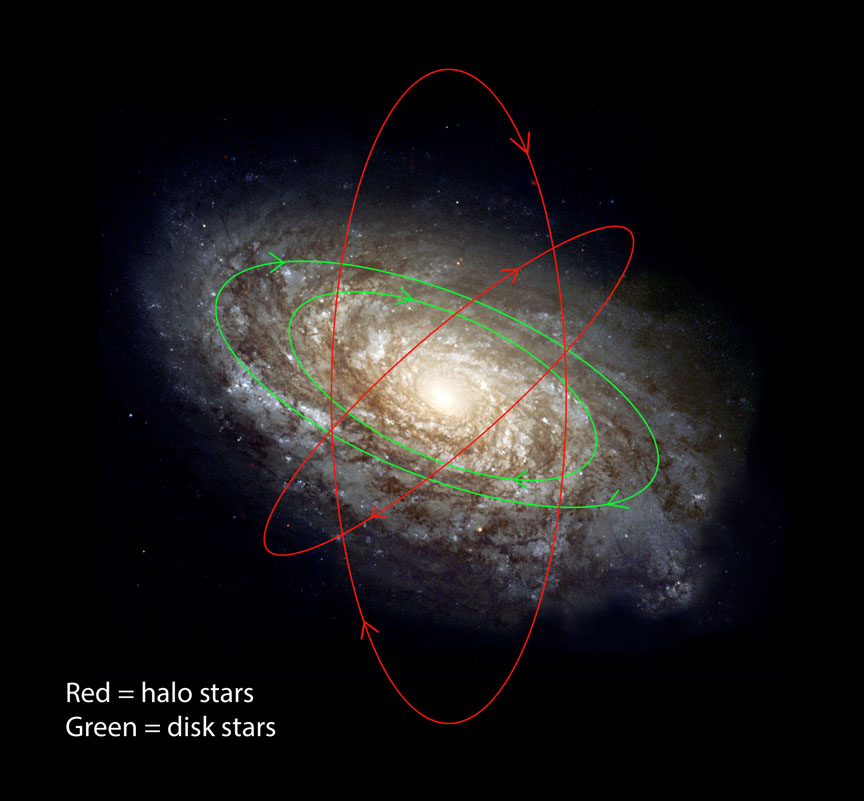

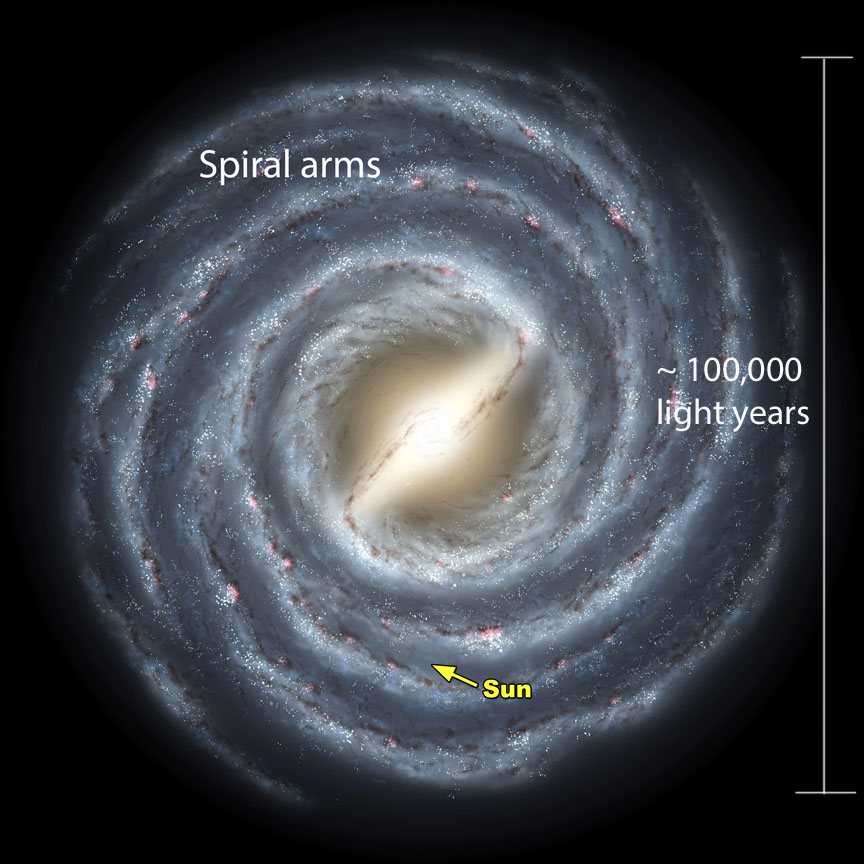

Stars are incredibly far away. I could throw light years around like I often do here, but the fact is, you can get a real feel for their distance by noting that during your lifetime, none will appear to move individually. The gems of the night and our sun alike revolve around the center of the galaxy. At our solar system’s distance from the center — 26,000 light years or about halfway from center to edge — it takes the sun about 225 million years to make one revolution around the Milky Way.

That’s a LONG time. The other stars we see on a September night take a similar length of time to orbit. Now divide the average lifetime of some 85 years into that number, and you’ll discover that an average star moves something like .00000038% of its orbit around the galactic center every generation. Phew, that ain’t much! No wonder most stars don’t budge in our lifetime.

Sirius, Aldebaran and Arcturus and several other telescopic stars are close enough that their motion across the sky becomes apparent within the span of recorded history. More powerful telescopes, which expand the scale of the sky, can see a great many stars amble within a human lifetime. Sadly, our eyes alone only work at low power!

But we needn’t invest billions in building a time machine to zing to the future or past to see how the constellation outlines become distorted by the individual motions of the stars that compose them. We already have one! Just fire up a free sky charting software program like Stellarium and advance the clock. Like most such programs, it defaults to the present, but let’s look ahead. Far ahead.

If we advance 90,000 years into the future, many of the constellations would be unrecognizable. Not only that, but more locally, the precession of Earth’s axis causes the polestar to shift. In 2016, Polaris in the Little Dipper stands at the northernmost point in the sky, but in 90,000 years the brilliant star Vega will occupy the spot. Tugs from the sun and moon on Earth’s equatorial bulge cause its axis to gyrate in a circle over a period of about 26,000 years. Wherever the axis points defines the polestar.

Take a look at the Big Dipper. Wow! It’s totally bent out of shape yet still recognizable. The Pointer Stars no longer quite point to Polaris, but with some fudging we might make it work. Vega stands near the pole, and being much closer to us than the rest of Lyra’s stars, has moved considerably farther north, stretching the outline of the constellation as if taffy.

Time goes on. We look up at the night sky in the present moment, but so much came before us and much will come after. Constellations were unrecognizable in the past and will be again in the future. In a fascinating discussion with Michael Kauper of the Minnesota Astronomical Society at a recent star party, he described the amount of space in and between galaxies as so enormous that “we’re almost not here” in comparison. I would add that time is so vast we’re likewise almost not present. Make the most of the moment.

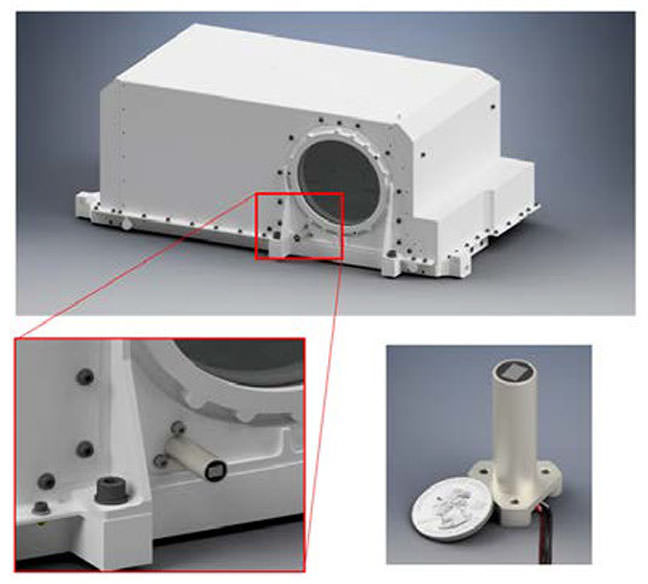

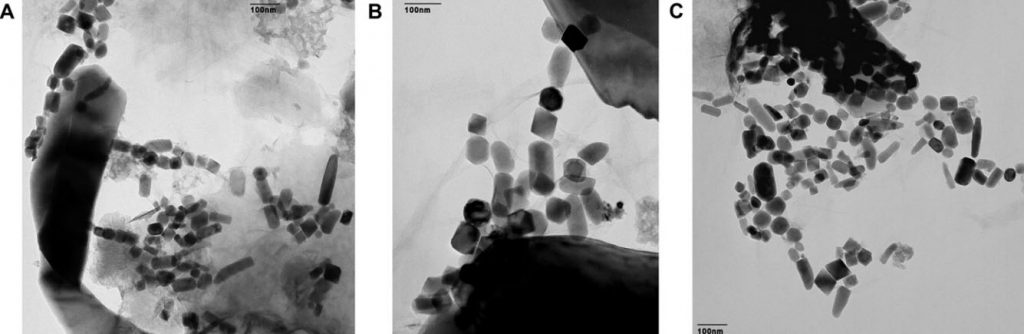

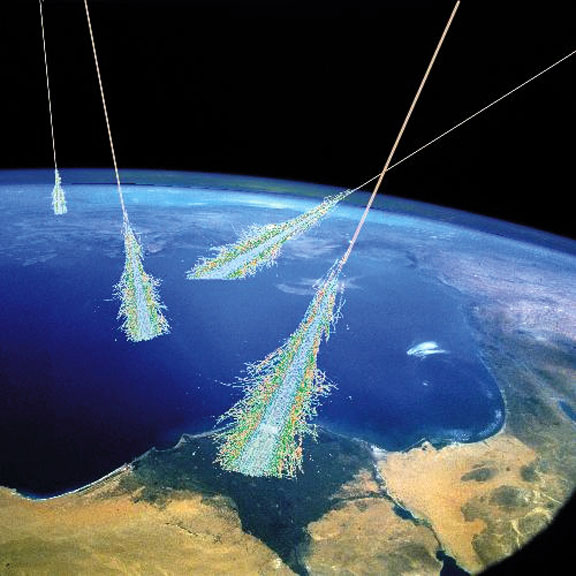

![Ever burnt meat or grilled chicken till the skin was crisp? In the process, the meats released PAHs, complex molecules composed of carbon (shown here at "C") and hydrogen ("H"). This ball-and-stick figure represents benzo[a]pyrene, a PAH commonly produced when cooking food or burning wood has 20 carbon atoms and a dozen hydrogens. Credit: Dennis Bogdan with additions by the author](https://astrobob.areavoices.com/files/2016/08/PAH-Benzoapyrene_Dr_Dennis_Bogdan_wikiANNO.jpg)