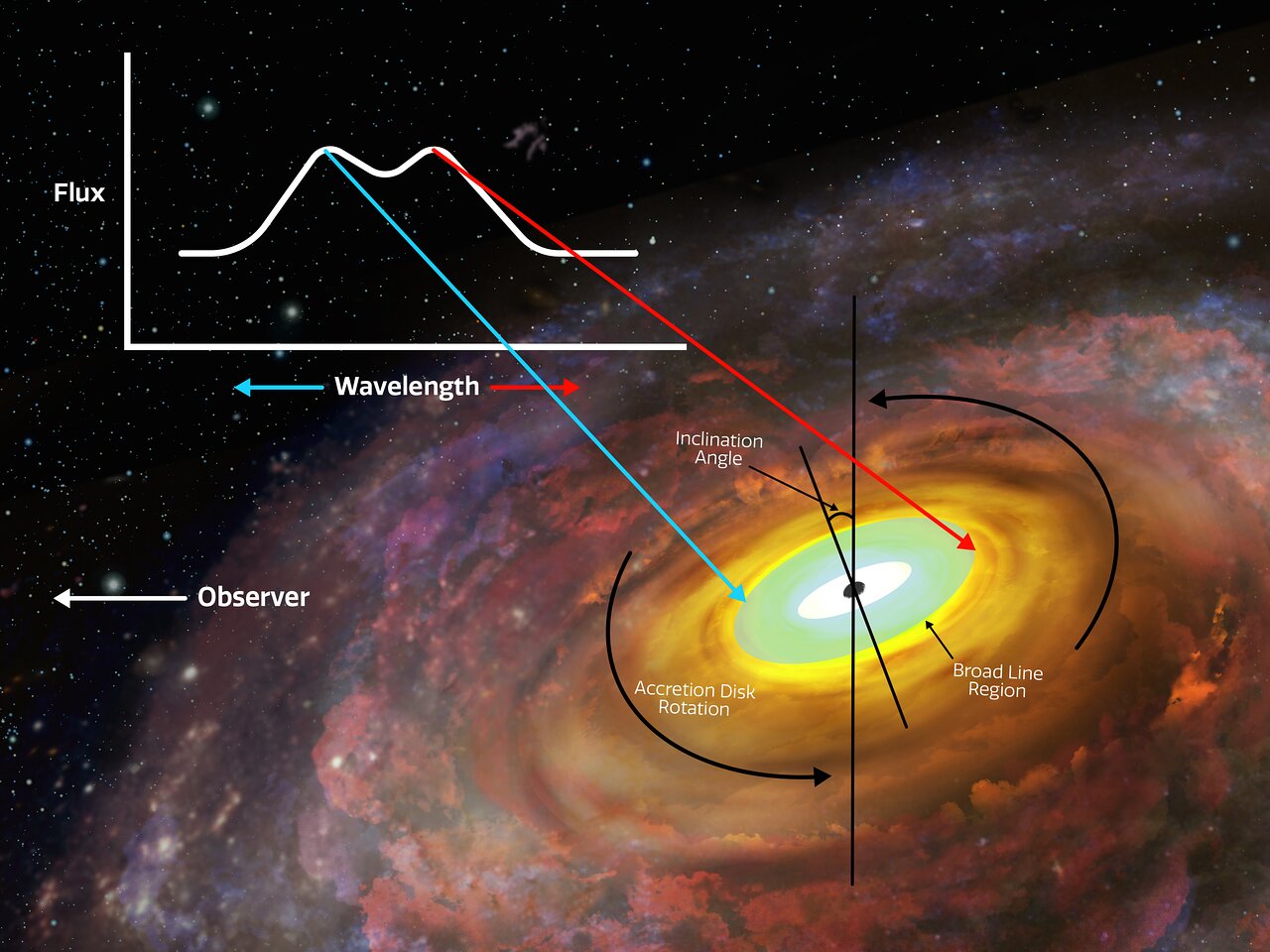

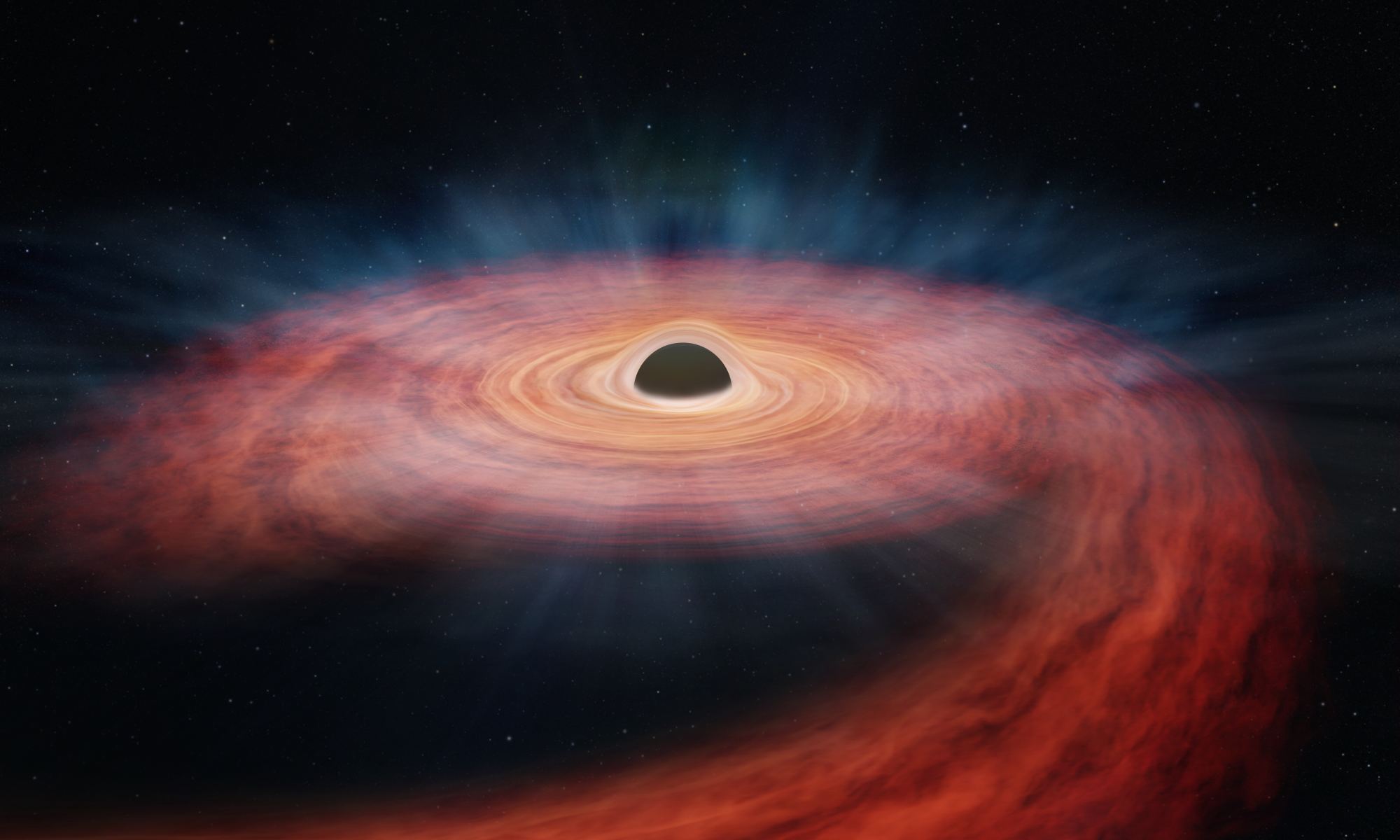

When you think of a black hole, you might think its defining feature is its event horizon. That point of no return not even light can escape. While it’s true that all black holes have an event horizon, a more critical feature is the disk of hot gas and dust circling it, known as the accretion disk. And a team of astronomers have made the first direct measure of one.

Continue reading “Astronomers Precisely Measure a Black Hole's Accretion Disk”The Early Universe Should Be Awash in Active Galaxies, but JWST Isn't Finding Them

For decades the most distant objects we could see were quasars. We now know they are powerful active black holes. Active galactic nuclei so distant that they resemble star-like points of light. It tells us that supermassive black holes in the early Universe can be powerful monsters that drive the evolution of their galaxies. We had thought most early supermassive black holes went through such an active phase, but a new study suggests most supermassive black holes don’t.

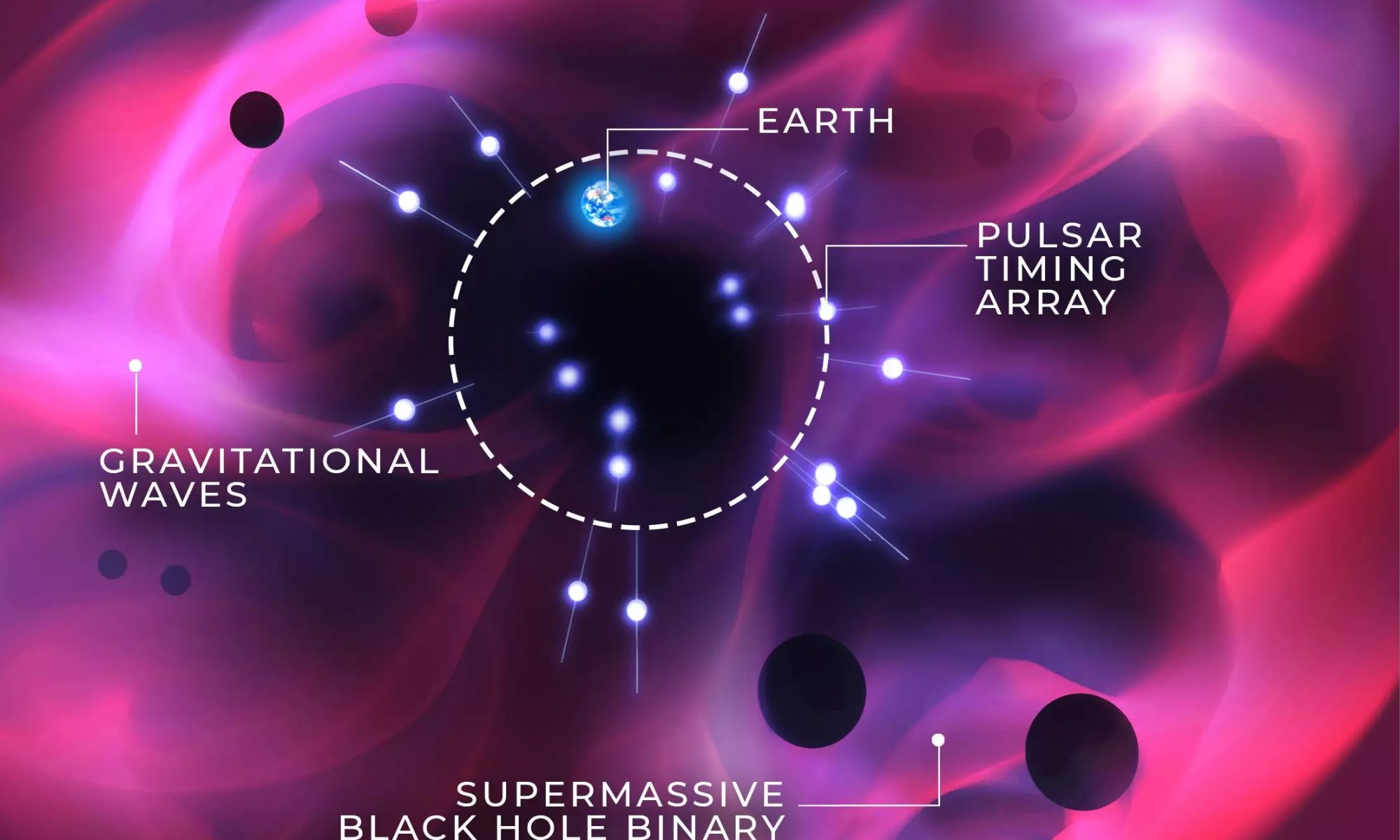

Continue reading “The Early Universe Should Be Awash in Active Galaxies, but JWST Isn't Finding Them”Pulsars Detected the Background Gravitational Hum of the Universe. Now Can They Detect Single Mergers?

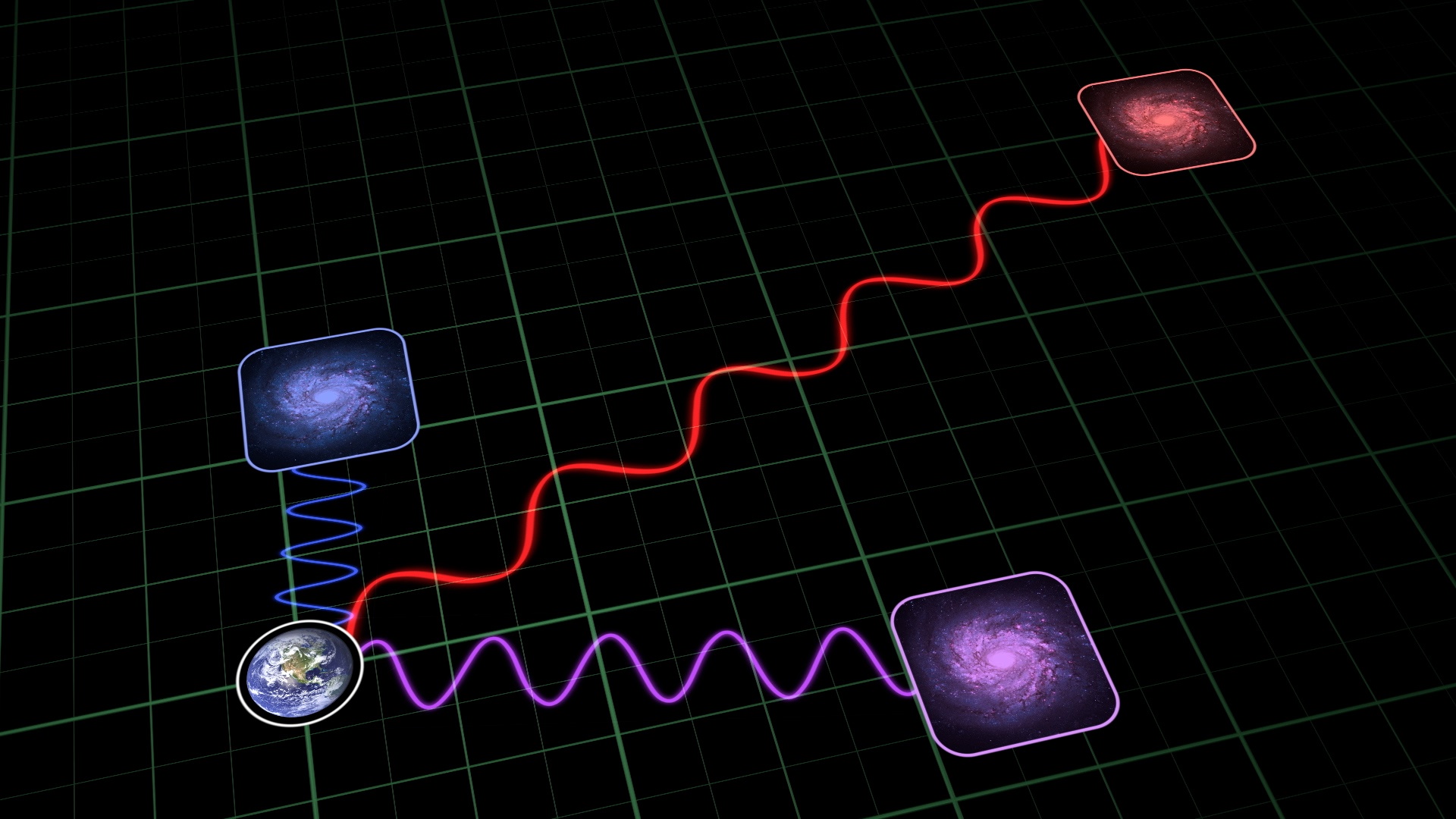

Current gravitational wave observatories have two significant limitations. The first is that they can only observe powerful gravitational bursts such as the mergers of black holes and neutron stars. The second is that they can only observe these mergers for wavelengths on the order of hundreds to thousands of kilometers. This means we can only observe stellar mass mergers. Of course, there’s a lot of interesting gravitational astronomy going on at other wavelengths and noise levels, which has motivated astronomers to get clever. One of these clever ideas is to use pulsars as a telescope.

Continue reading “Pulsars Detected the Background Gravitational Hum of the Universe. Now Can They Detect Single Mergers?”A Giant Black Hole Destroyed a Star and Threw the Pieces Into Space

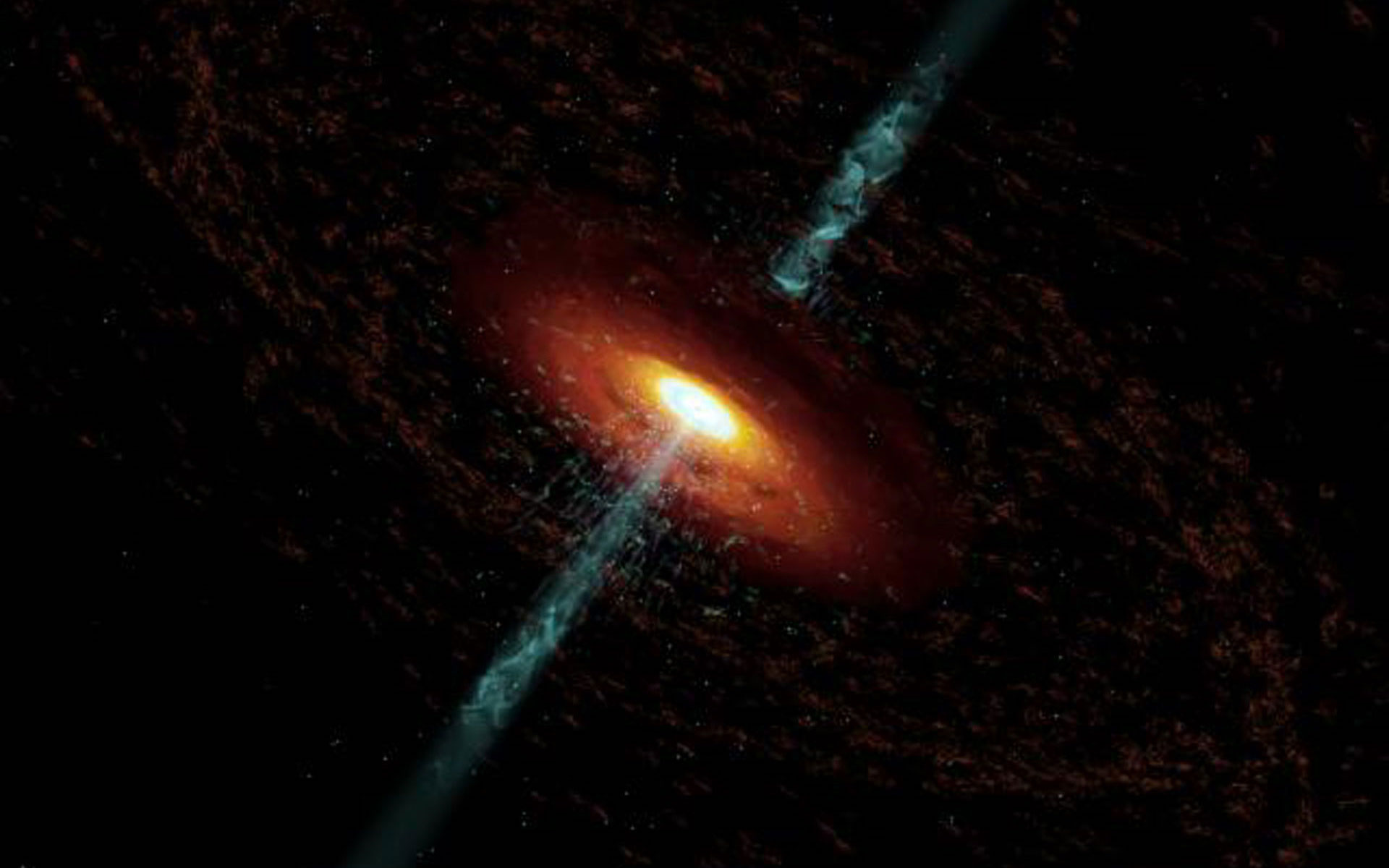

When a black hole consumes a star, things can get quite messy. Take, for example, the event known as ASASSN-14li, where a massive star strayed too close to a supermassive black hole and paid the ultimate price.

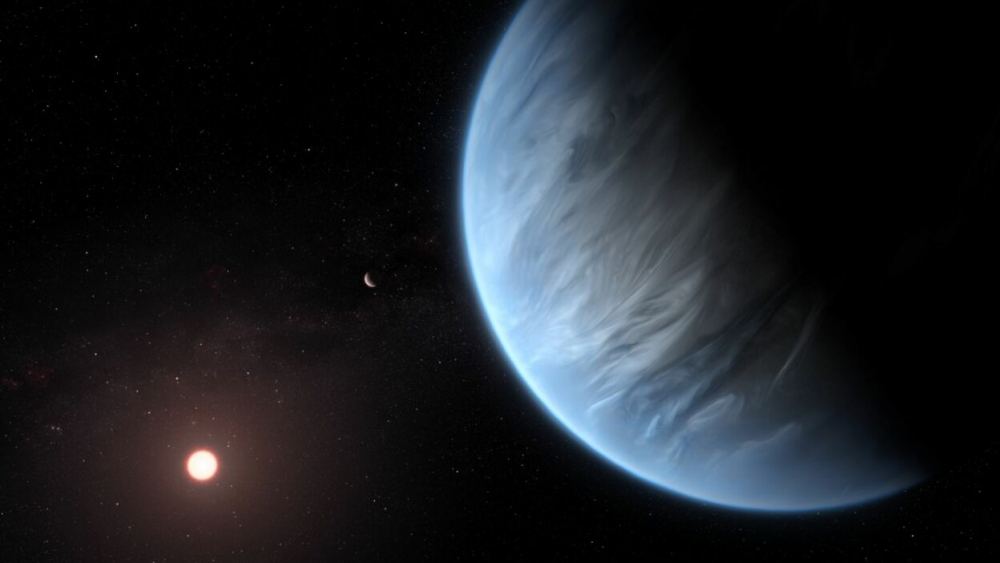

Continue reading “A Giant Black Hole Destroyed a Star and Threw the Pieces Into Space”TESS Has Found Thousands of Possible Exoplanets. Which Ones Should JWST Study?

There are more than 5,000 confirmed exoplanets in our galaxy. That number is going to rise significantly in the next decade. The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) has already cataloged more than 4,000 candidate exoplanets, and the PLAnetary Transits and Oscillations of stars (PLATO) is scheduled to launch in 2026. We will soon have more than 10,000 worlds where life might be able to survive. It’s an amazing idea, but with so many exoplanets we don’t have the resources to search for life on all of them. So how do we prioritize our search?

Continue reading “TESS Has Found Thousands of Possible Exoplanets. Which Ones Should JWST Study?”The Irony. ClearSpace-1 Couldn't Clean up Space Debris Because its Target Already Got hit by Space Debris, Creating Even More Space Debris.

We have a problem.

Ever since the launch of Sputnik 1 in 1957, we have been launching debris into space. Everything from space stations and large communication satellites to small CubeSats. With each launch, we also add things such as rocket parts and paint chips to the orbital pile. Right now there are more than a million objects orbiting Earth wider than a centimeter, and at least 130 million millimeter-sized objects. Most of it isn’t going to deorbit any time soon.

Continue reading “The Irony. ClearSpace-1 Couldn't Clean up Space Debris Because its Target Already Got hit by Space Debris, Creating Even More Space Debris.”When the Sun Dies, it Could Produce a Fantastic Ring in Space, Like This New Image From JWST

Planetary nebulae were first discovered in the 1700s. Legend tells us that through the small telescopes of the time, they looked rather planet-like, hence the name. Real history is a bit more fuzzy, and early objects categorized as planetary nebulae included things such as galaxies. But the term stuck when applied to circular emission nebulae centered around a dying star. As new observations show, planetary nebulae have a structure that is both simple and complex.

Continue reading “When the Sun Dies, it Could Produce a Fantastic Ring in Space, Like This New Image From JWST”A New Way to Measure the Expansion Rate of the Universe: Redshift Drift

In 1929 Edwin Hubble published the first solid evidence that the universe is expanding. Drawing upon data from Vesto Slipher and Henrietta Leavitt, Hubble demonstrated a correlation between galactic distance and redshift. The more distant a galaxy was, the more its light appeared shifted to the red end of the spectrum. We now know this is due to cosmic expansion. Space itself is expanding, which makes distant galaxies appear to recede away from us. The rate of this expansion is known as the Hubble parameter, and while we have a good idea of its value, there is still a bit of tension between different results.

Continue reading “A New Way to Measure the Expansion Rate of the Universe: Redshift Drift”A New Simulation Reveals One Entire Stage of a Star's Life

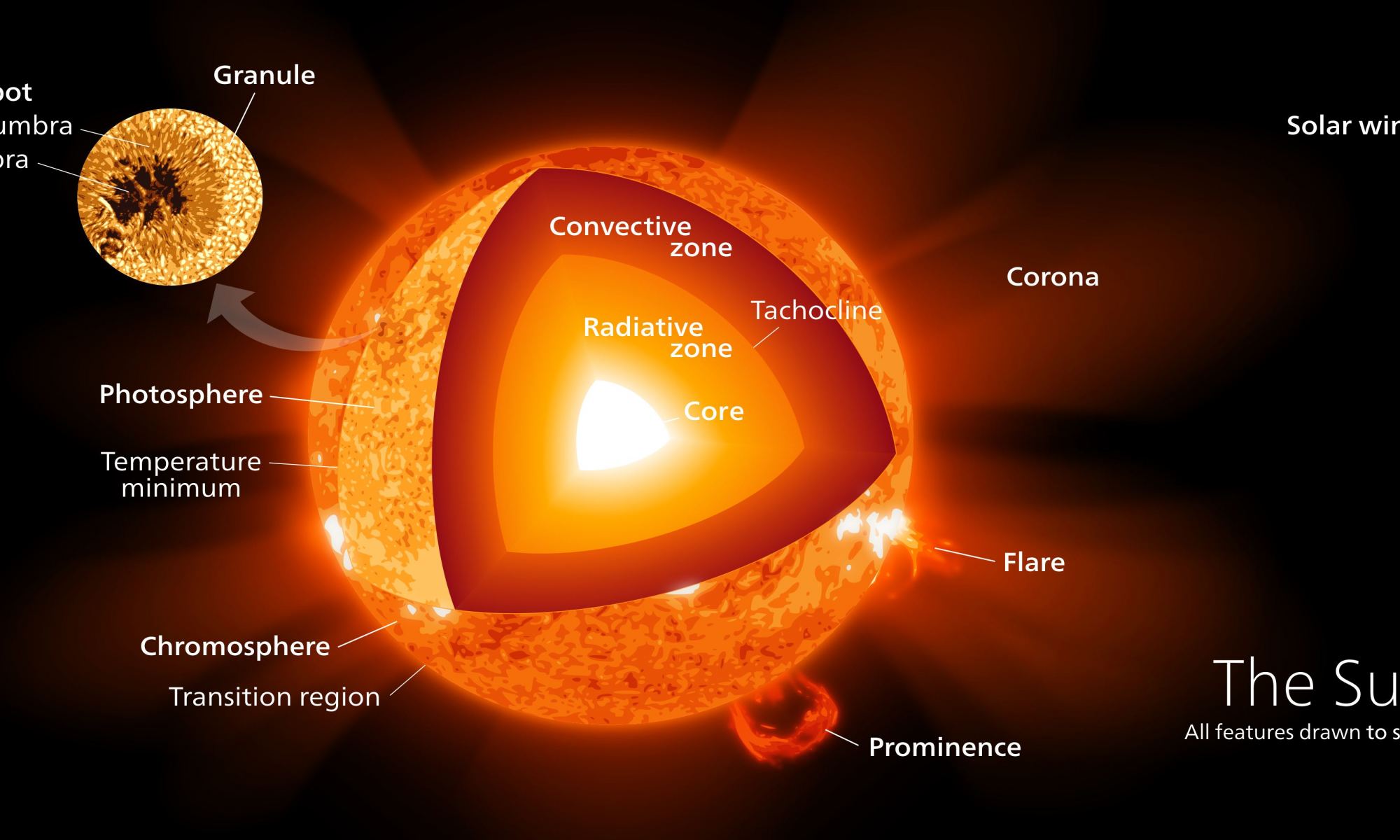

Nuclear fusion is at the center of stellar evolution. Most of a star’s life is a battle between gravity and nuclear power. While we understand this process on a broad scale, many of the details still elude us. We can’t dive into a star to see its nuclear furnace, so we rely on complex computer simulations. A recent study has made a big step forward by modeling the entire fusion cycle of a single element.

Continue reading “A New Simulation Reveals One Entire Stage of a Star's Life”We Might Be Able to Measure Dark Energy Through the Milky Way's Collision With Andromeda

The Universe is expanding, and it’s doing so at an ever-increasing pace. Whether due to a dark energy field throughout the cosmos or due to a fundamental of spacetime itself, the cosmos is stretching the space between distant galaxies. But nearby galaxies, those part of our local group, are moving closer together. And how they are falling toward each other could tell us about the nature of cosmic expansion.

Continue reading “We Might Be Able to Measure Dark Energy Through the Milky Way's Collision With Andromeda”