The universe is governed by four fundamental forces: gravity, electromagnetism, and the strong and weak nuclear forces. These forces drive the motion and behavior of everything we see around us. At least that’s what we think. But over the past several years there’s been increasing evidence of a fifth fundamental force. New research hasn’t discovered this fifth force, but it does show that we still don’t fully understand these cosmic forces.

Continue reading “A Fifth Fundamental Force Could Really Exist, But We Haven’t Found It Yet”How Large Can A Planet Be?

Jupiter is the largest planet in the solar system. In terms of mass, Jupiter towers over the other planets. If you were to gather all the other planets together into a single mass, Jupiter would still be 2.5 times more massive. It is hard to understate just how huge Jupiter is. But as we’ve discovered thousands of exoplanets in recent decades, it raises an interesting question about how Jupiter compares. Put another way, just how large can a planet be? The answer is more subtle than you might think.

Continue reading “How Large Can A Planet Be?”New Research Suggests that the Universe is a Sphere and Not Flat After All

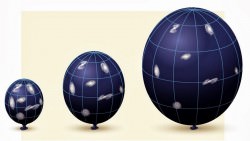

The universe is a seemingly endless sea filled with stars, galaxies, and nebulae. In it, we see patterns and constellations that have inspired stories throughout history. But there is one cosmic pattern we still don’t understand. A question that remains unanswered: What is the shape of the universe? We thought we knew, but new research suggests otherwise, and it could point to a crisis in cosmology.

Continue reading “New Research Suggests that the Universe is a Sphere and Not Flat After All”What Was The First Color In The Universe?

The universe bathes in a sea of light, from the blue-white flickering of young stars to the deep red glow of hydrogen clouds. Beyond the colors seen by human eyes, there are flashes of x-rays and gamma rays, powerful bursts of radio, and the faint, ever-present glow of the cosmic microwave background. The cosmos is filled with colors seen and unseen, ancient and new. But of all these, there was one color that appeared before all the others, the first color of the universe.

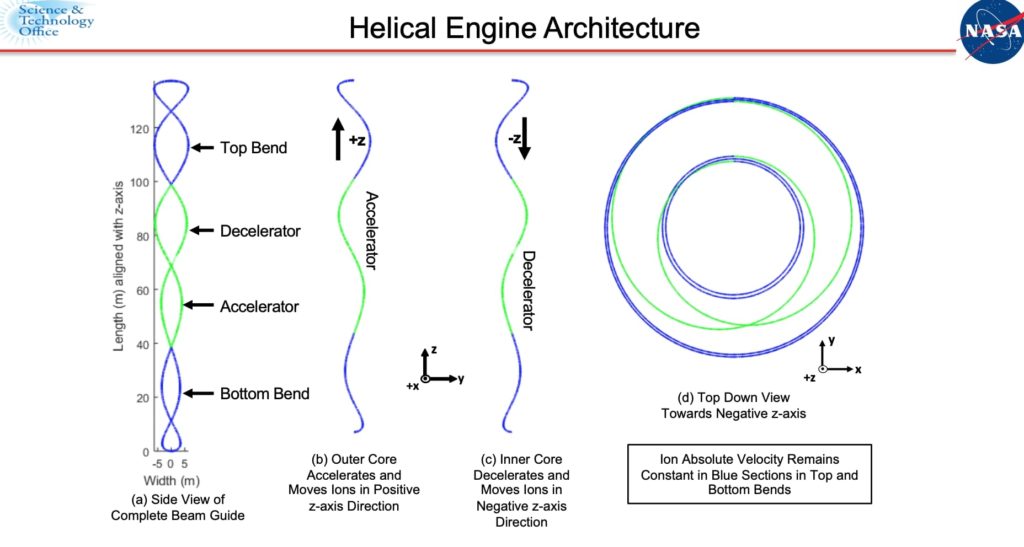

Continue reading “What Was The First Color In The Universe?”NASA Engineer Has A Great Idea for a High-Speed Spacedrive. Too Bad it Violates the Laws of Physics

When a NASA engineer announces a new and revolutionary engine that could take us to the stars, it’s easy to get excited. But the demons are in the details, and when you look at the actual article things look far less promising.

Continue reading “NASA Engineer Has A Great Idea for a High-Speed Spacedrive. Too Bad it Violates the Laws of Physics”A Different Kind Of Science Show

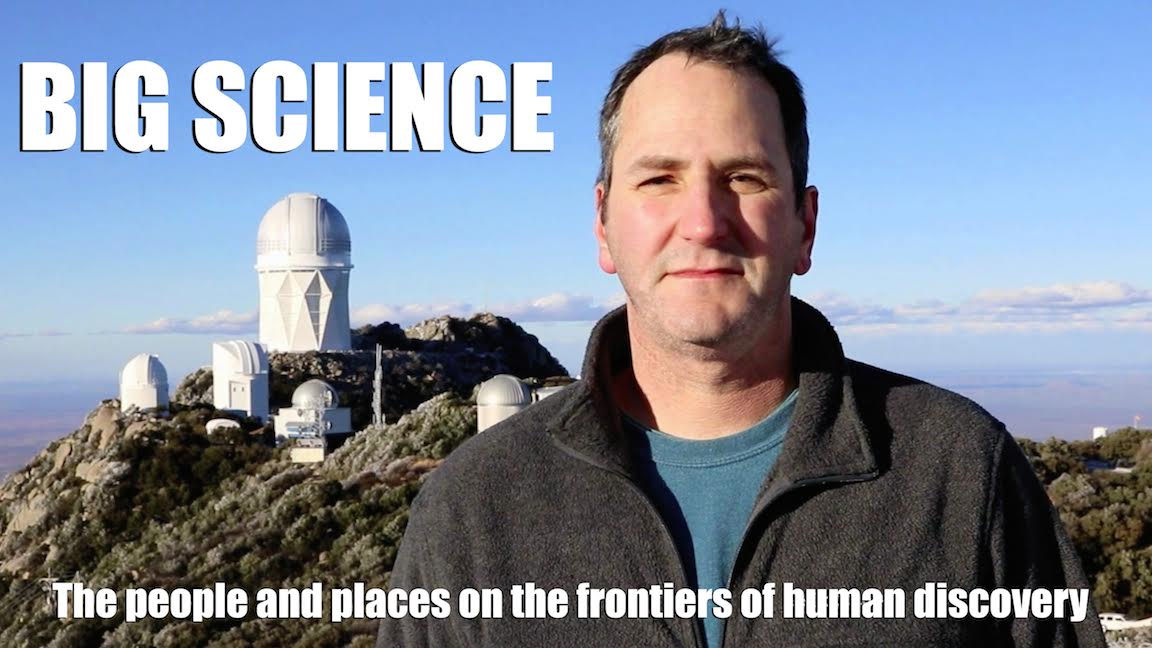

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/64470060/big-science

When I visited the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory a few years ago, the facility lost power. The observatory is in a remote area of northern Chile, so you can’t just call the power company to complain. Fortunately there’s a skilled team of technicians on the job. Their first priority was to maintain the cooling system of the large Blanco telescope. It contains an array of 62 CCDs known as the Dark Energy Camera, which must be kept cold. Discussing the matter in a mix of English and Spanish, the team worked through the challenge of rigging generators to the telescope. Meanwhile the CTIO kitchen staff had to figure out how to feed dozens of people without electricity. With portable gas cookers they prepare baked fish and steamed rice, with ample hot water for tea and coffee. Meanwhile, facility administrators were coordinating with the Chilean electrical grid to restore power to the observatory. By the end of the day everything was back up and running.

Whenever CTIO or other large science facilities make a breakthrough discovery, we hear about it all over the web. What we don’t hear about is the work done behind the scenes. We don’t hear about the technicians who saved a million dollar camera, or the staff who ensure that everyone is safe and fed, or the machinists who build and maintain these facilities. We also don’t hear about how these remote facilities interact with neighboring communities. How they face the challenge of being good neighbors while pursuing their scientific goals. These are stories worth telling, which is why I’ve been working on a new television project.

For about a year I’ve been working with journalist Mark Gillespie, and Canadian TV producers Steven Mitchell and Al Magee to develop a new kind of science show. One that will tell the stories behind the science headlines. Steven and Al have decades of experience in television storytelling, and have won several awards for their outstanding work. They also share my desire to present science honestly and without hype. Mark has worked in some of the most remote areas of the world, and knows how bring out stories that are meaningful and powerful.

We’ve already developed relations with many big science facilities, and we know several stories we want to tell. But in order for the project to succeed we need to film a “sizzle reel” demonstrating the show to the networks. It will be filmed on location at Green Bank Observatory. But it’s going to take some funding, so we’ve launched a Kickstarter campaign. You can find the project at https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/64470060/big-science.

Science is not just about breakthrough discoveries. It’s about people coming together to do extraordinary things. I hope you’ll help us tell this story.

How Fast is the Universe Expanding?

The Universe is expanding, but how quickly is it expanding? How far away is everything getting from everything else? And how do we know any of this anyway?

When astronomers talk about the expansion of the Universe, they usually express it in terms of the Hubble parameter. First introduced by Edwin Hubble when he demonstrated that more distant galaxies are moving away from us faster than closer ones.The best measurements for this parameter gives a value of about 68 km/s per megaparsec.

Let’s recap. Hubble. Universe. Galaxies. Leaving. Further means faster. And then I said something that sounded like “blah blah Lando blah blah Kessel Run 68 km/s per megaparsec”. Which translates to if you have a galaxy 1 megaparsec away, that’s 3.3 million light years for those of you who haven’t seen Star Wars, it would be expanding away from us at a speed of 68 km/s. So, 1 megaparsec in distance means it’s racing away at 68 km/s.

This is all because space is expanding everywhere in all places, and as a result distant galaxies appear to be expanding away from us faster than closer ones. There’s just more “space” to expand between us and them in the first place. Even better, our Universe was much more dense in the past, as a result the Hubble parameter hasn’t always had the same value.

There are two things affecting the Hubble parameter: dark energy, working to drive the Universe outwards, and matter, dark and regular flavor trying to hold it together. Pro tip: The matter side of this fight is currently losing.

Earlier in the Universe, when the Hubble parameter was smaller, matter had a stronger influence due to its higher overall density. Today dark energy is dominant, thus the Hubble parameter is larger, and this is why we talk about the Universe not only expanding but accelerating.

Our cosmos expands at about the rate at which space is expanding, and the speed at which objects expand away from us depends upon their distance. If you go far enough out, there is a distance at which objects are speeding away from us faster than the speed of light. As a result, it’s suspected that receding galaxies will cross a type of cosmological event horizon, where any evidence of their existence, not even light, would ever be able to reach us, no matter how far into the future you went.

What do you think? Is there anything out there past that cosmological event horizon line waiting to surprise us?

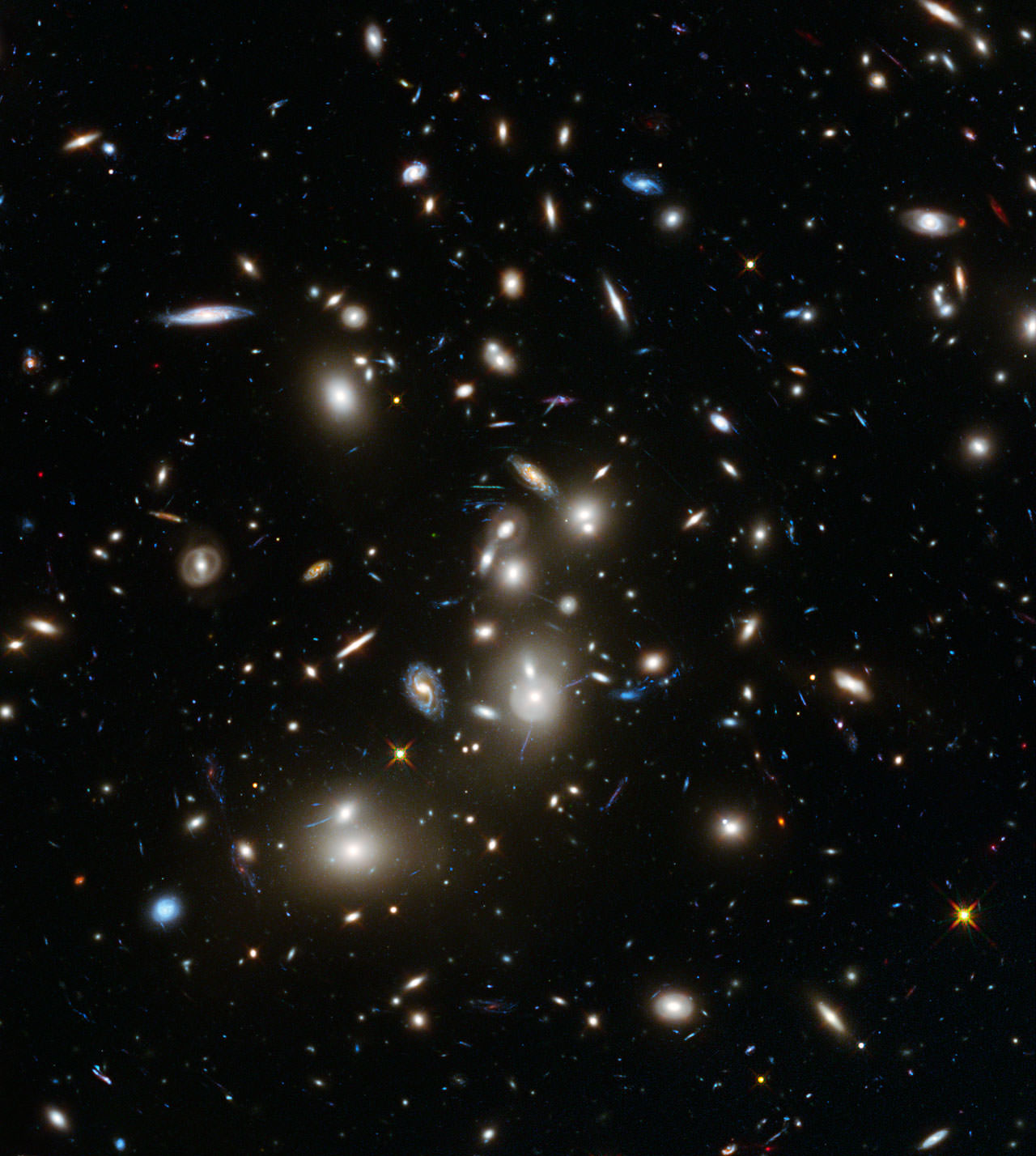

What is Gravitational Lensing?

Gravity’s a funny thing. Not only does it tug away at you, me, planets, moons and stars, but it can even bend light itself. And once you’re bending light, well, you’ve got yourself a telescope.

Everyone here is familiar with the practical applications of gravity. If not just from exposure to Loony Tunes, with an abundance of scenes with an anthropomorphized coyote being hurled at the ground from gravitational acceleration, giant rocks plummeting to a spot inevitably marked with an X, previously occupied by a member of the “accelerati incredibilus” family and soon to be a big squish mark containing the bodily remains of the previously mentioned Wile E. Coyote.

Despite having a very limited understanding of it, Gravity is a pretty amazing force, not just for decimating a infinitely resurrecting coyote, but for keeping our feet on the ground and our planet in just the right spot around our Sun. The force due to gravity has got a whole bag of tricks, and reaches across Universal distances. But one of its best tricks is how it acts like a lens, magnifying distant objects for astronomy.

Continue reading “What is Gravitational Lensing?”What Came Before the Big Bang?

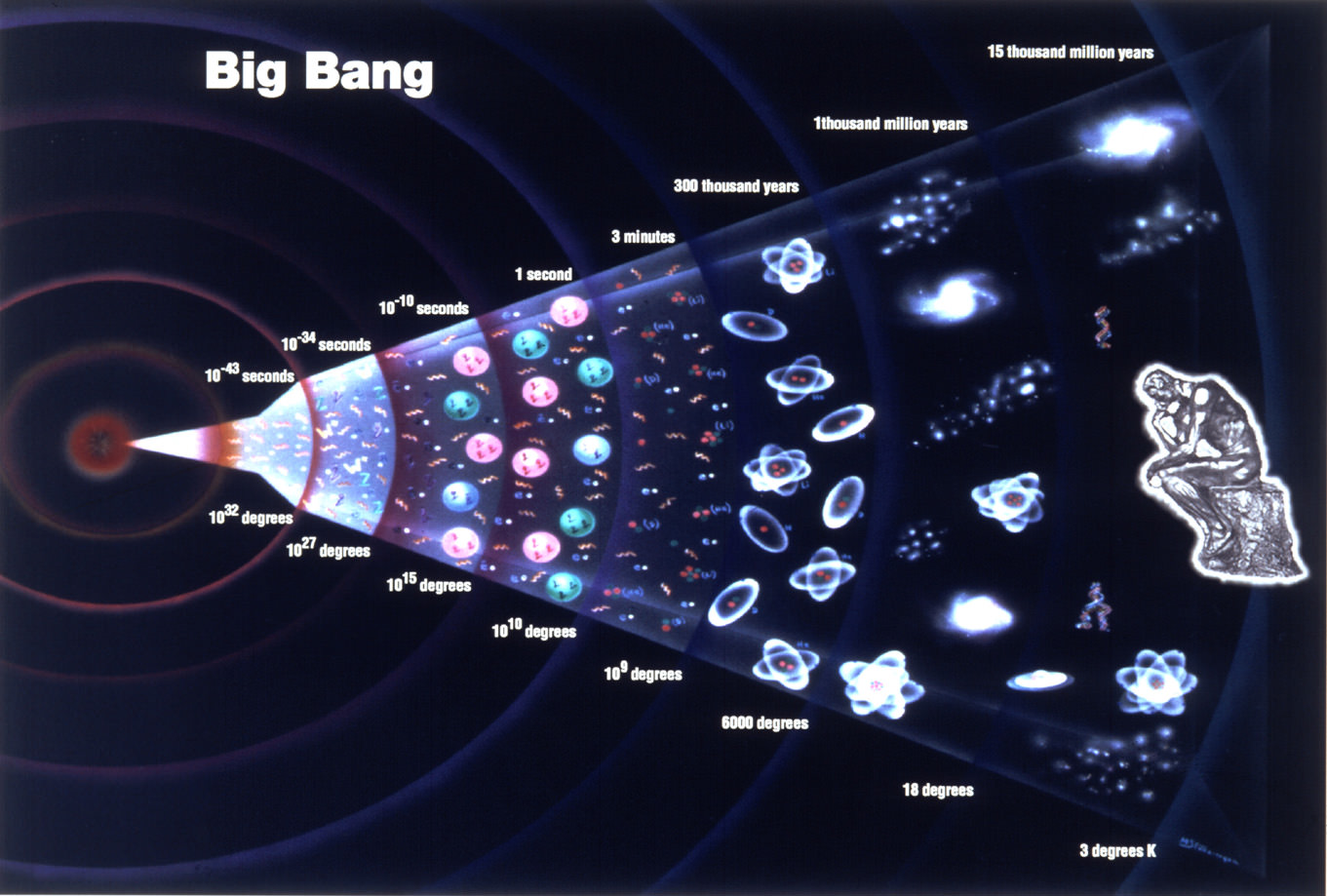

Astronomers are pretty sure what happened after the Big Bang, but what came before? What are the leading theories for the causes of the Big Bang?

About 13.8 billion years ago the Universe started with a bang, kicked the doors in, brought fancy cheeses and a bag of ice, spiked the punch bowl and invited the new neighbors over for all-nighter to encompass all all-nighters from that point forward.

But what happened before that?

What was going on before the Big Bang? Usually, we tell the story of the Universe by starting at the Big Bang and then talking about what happened after. Similarly and completely opposite to how astronomers view the Universe… by standing in the present and looking backwards. From here, the furthest we can look back is to the cosmic microwave background, which is about 380,000 years after the big bang.

Before that we couldn’t hope to see a thing, the Universe was just too hot and dense to be transparent. Like pea soup. Soup made of delicious face burning high energy everything.

In traditional stupid earth-bound no-Tardis life unsatisfactory fashion, we can’t actually observe the origin of the Universe from our place in time and space.

Damn you… place in time and space.

Fortunately, the thinky types have come up with some ideas, and they’re all one part crazy, one part mind bendy, and 100% bananas. The first idea is that it all began as a kind of quantum fluctuation that inflated to our present universe.

Something very, very subtle expanding over time resulting in, as an accidental byproduct, our existence. The alternate idea is that our universe began within a black hole of an older universe.

I’m gonna let you think about that one. Just let your brain simmer there.

There was universe “here”, that isn’t our universe, then that universe became a black hole… and from that black hole formed us and EVERYTHING around us. Literally, everything around us. In every direction we look, and even the stuff we just assume to be out there.

Here’s another one. We see particles popping into existence here in our Universe. What if, after an immense amount of time, a whole Universe’s worth of particles all popped into existence at the same time. Seriously… an immense amount of time, with lots and lots of “almost” universes that didn’t make the cut.

More recently, the BICEP2 team observed what may be evidence of inflation in the early Universe.

Like any claim of this gravity, the result is hotly debated. If the idea of inflation is correct, it is possible that our universe is part of a much larger multiverse. And the most popular form would produce a kind of eternal inflation, where universes are springing up all the time. Ours would just happen to be one of them.

It is also possible that asking what came before the big bang is much like asking what is north of the North Pole. What looks like a beginning in need of a cause may just be due to our own perspective. We like to think of effects always having a cause, but the Universe might be an exception. The Universe might simply be. Because.

You tell us. What was going on before the party started? Let us know in the comments below.

And if you like what you see, come check out our Patreon page and find out how you can get these videos early while helping us bring you more great content!

How are Energy and Matter the Same?

As Einstein showed us, light and matter and just aspects of the same thing. Matter is just frozen light. And light is matter on the move. How does one become the other?

Albert Einstein’s most famous equation says that energy and matter are two sides of the same coin.

But what does that really mean? And how are equations famous? I like to believe equations can be famous in the way a work of art, or a philosophy can be famous. People can have awareness of the thing, and yet never have interacted with it. They can understand that it is important, and yet not understand why it’s so significant. Which is a little too bad, as this is really a lovely mind bending idea.

The origin of E=mc2 lies in special relativity. Light has the same speed no matter what frame of reference you are in. No matter where you are, or how fast you’re going. If you were standing still at the side of the road, and observed a car traveling at ¾ light speed, you would see the light from their headlights traveling away from them at ¼ the speed of light.

But the driver of the car would still see that the light moving ahead of them at the speed of light. This is only possible if their time appears to slow down relative to you, and you and the people in the car can no longer agree on how long a second would take to pass.

So the light appears to be moving away from them more slowly, but as they experience things more slowly it all evens out. This also affects their apparent mass. If they step on the gas, they will speed up more slowly than you would expect. It’s as if the car has more mass than you expect. So relativity requires that the faster an object moves, the more mass it appears to have. This means that somehow part of the energy of the car’s motion appears to transform into mass. Hence the origin of Einstein’s equation. How does that happen? We don’t really know. We only know that it does.

The same effect occurs with quantum particles, and not just with light. A neutron, for example, can decay into a proton, electron and anti-neutrino. The mass of these three particles is less than the mass of a neutron, so they each get some energy as well. So energy and matter are really the same thing. Completely interchangeable. And finally, Although energy and mass are related through special relativity, mass and space are related through general relativity. You can define any mass by a distance known as its Schwarzschild radius, which is the radius of a black hole of that mass. So in a way, energy, matter, space and time are all aspects of the same thing.

What do you think? Like E=mc2, what’s the most famous idea you can think of in physics?

And if you like what you see, come check out our Patreon page and find out how you can get these videos early while helping us bring you more great content!