[/caption]

Compared to Earth, Mercury doesn’t have much of an atmosphere. The smallest rocky planet has weak surface gravity, only 38% that of Earth. And the scorching-hot daytime surface temperatures of 800 degrees Fahrenheit (approximately 450 degrees Celsius) should have boiled away any trace of Mercury’s atmosphere long ago. Yet recent flybys of the MESSENGER spacecraft clearly revealed Mercury somehow retains a thin layer of gas near its surface. Where does this atmosphere come from?

“Mercury’s atmosphere is so thin, it would have vanished long ago unless something was replenishing it,” says Dr. James A. Slavin of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md., a co-investigator on NASA’s MESSENGER mission to Mercury.

The solar wind may well be the culprit. A thin gas of electrically charged particles called a plasma, the solar wind blows constantly from the surface of the sun at some 250 to 370 miles per second (about 400 to 600 kilometers/second). According to Slavin, that’s fast enough to blast off the surface of Mercury through a process called “sputtering”, according to Slavin. Some sputtered atoms stay close enough to the surface to serve as a tenuous yet measurable atmosphere.

But there’s a catch – Mercury’s magnetic field gets in the way. MESSENGER’s first flyby on January 14, 2008, confirmed that the planet has a global magnetic field, as first discovered by the Mariner 10 spacecraft during its flybys of the planet in 1974 and 1975. Just as on Earth, the magnetic field should deflect charged particles away from the planet’s surface. However, global magnetic fields are leaky shields and, under the right conditions, they are known to develop holes through which the solar wind can hit the surface.

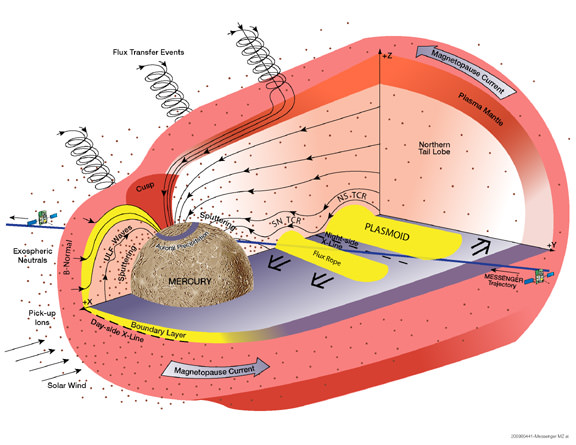

During its second flyby of the planet on October 6, 2008, MESSENGER discovered that Mercury’s magnetic field can be extremely leaky indeed. The spacecraft encountered magnetic “tornadoes” – twisted bundles of magnetic fields connecting the planetary magnetic field to interplanetary space – that were up to 500 miles wide or a third of the radius of the planet.

“These ‘tornadoes’ form when magnetic fields carried by the solar wind connect to Mercury’s magnetic field,” said Slavin. “As the solar wind blows past Mercury’s field, these joined magnetic fields are carried with it and twist up into vortex-like structures. These twisted magnetic flux tubes, technically known as flux transfer events, form open windows in the planet’s magnetic shield through which the solar wind may enter and directly impact Mercury’s surface.”

Venus, Earth, and even Mars have thick atmospheres compared to Mercury, so the solar wind never makes it to the surface of these planets, even if there is no global magnetic field in the way, as is the case for Venus and Mars. Instead, it hits the upper atmosphere of these worlds, where it has the opposite effect to that on Mercury, gradually stripping away atmospheric gas as it blows by.

The process of linking interplanetary and planetary magnetic fields, called magnetic reconnection, is common throughout the cosmos. It occurs in Earth’s magnetic field, where it generates magnetic tornadoes as well. However, the MESSENGER observations show the reconnection rate is ten times higher at Mercury.

“Mercury’s proximity to the sun only accounts for about a third of the reconnection rate we see,” said Slavin. “It will be exciting to see what’s special about Mercury to explain the rest. We’ll get more clues from MESSENGER’s third flyby on September 29, 2009, and when we get into orbit in March 2011.”

Slavin’s MESSENGER research was funded by NASA and is the subject of a paper that appeared in the journal Science on May 1, 2009.

MESSENGER (MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging) is a NASA-sponsored scientific investigation of the planet Mercury and the first space mission designed to orbit the planet closest to the Sun. The MESSENGER spacecraft launched on August 3, 2004, and after flybys of Earth, Venus, and Mercury will start a yearlong study of its target planet in March 2011. Dr. Sean C. Solomon, of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, leads the mission as Principal Investigator. The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, Laurel, Md., built and operates the MESSENGER spacecraft and manages this Discovery-class mission for NASA.

Source: NASA