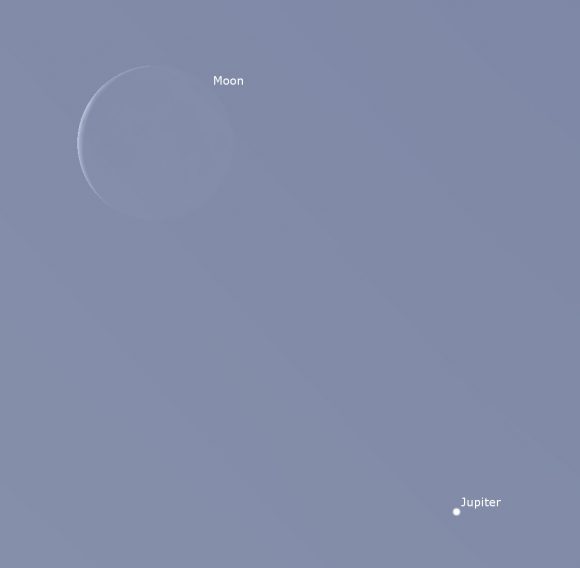

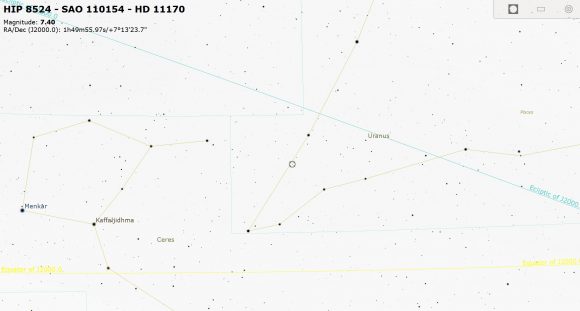

How about that Hunter’s Supermoon this past weekend, huh? Follow that Moon, as it’s meeting up with the Hyades again this week, and occults (passes in front of) Aldebaran Tuesday night into Wednesday morning.

Here’s the lowdown on the event:

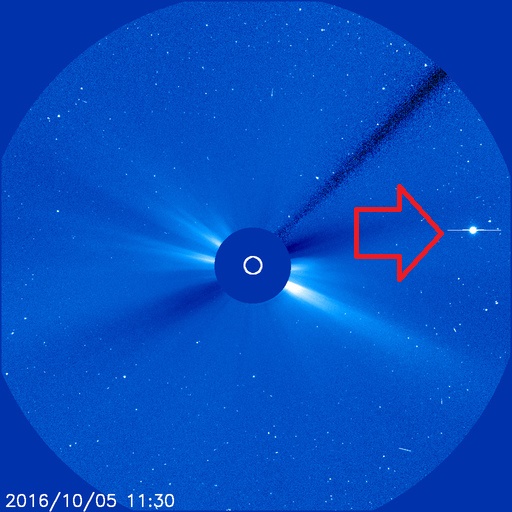

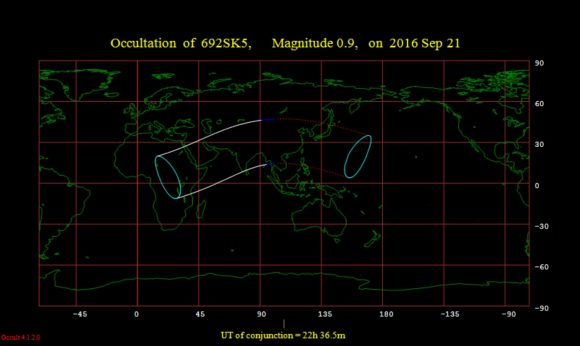

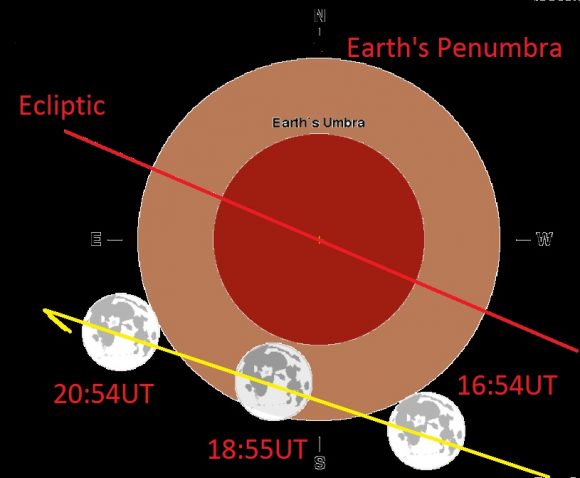

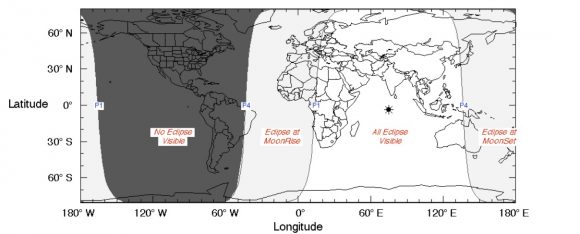

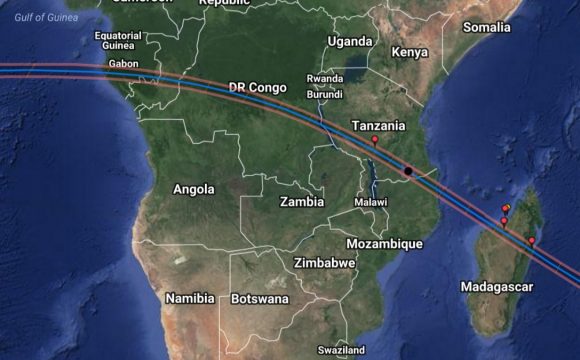

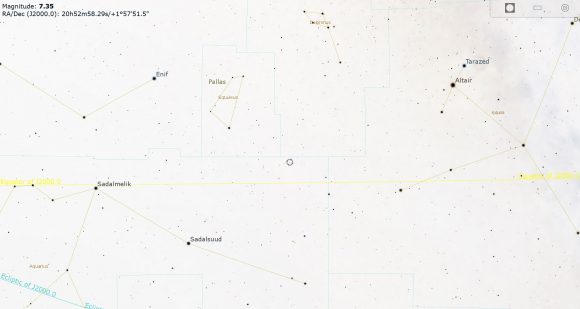

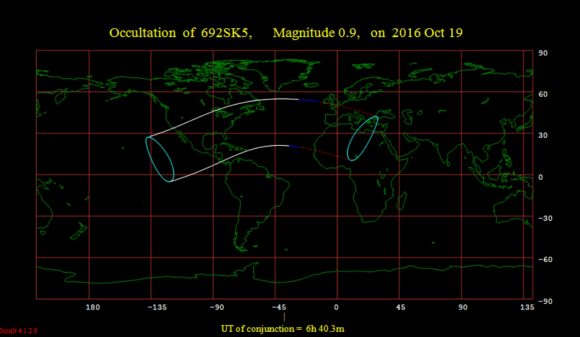

The 86% illuminated waning gibbous Moon occults the +0.9 magnitude star Aldebaran across North America, the Northern Atlantic and Europe. The Moon is three days past Full during the event. Both are located 136 degrees west of the Sun at the time of the event. The central time of conjunction is ~6:40 Universal Time (UT). The event occurs during the daylight hours over western Europe and northwestern Africa and under darkness for southeastern North America, including the eastern United States and Mexico. The Moon will next occult Aldebaran on November 15th, 2016. This is occultation 24 in the current series of 49 running from January 29th, 2015 to September 3rd 2018.

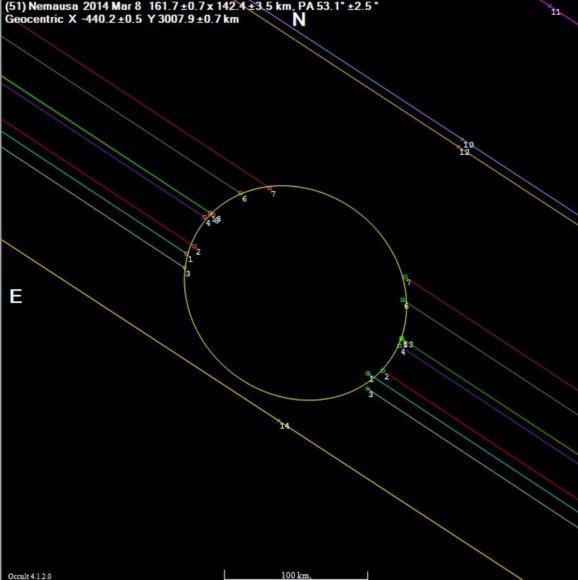

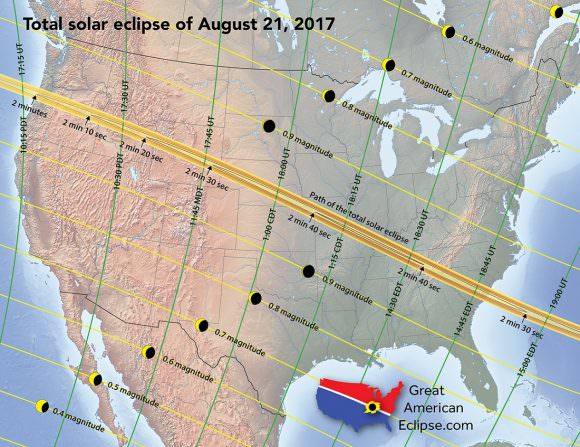

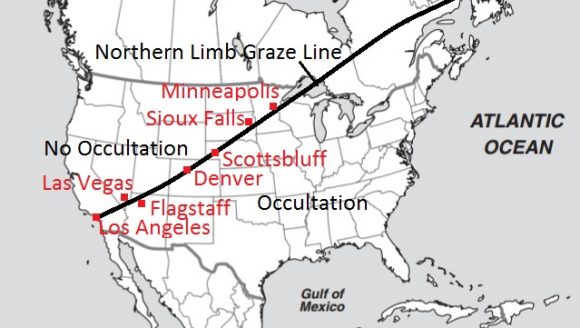

The graze line is of particular interest during this event. We’re talking about the very edge of the footprint of the Moon’s ‘shadow’ cast by Aldebaran, running through Canada and bisecting the United States. Observers based along this line could see a spectacular ‘grazing occultation’ of Aldebaran by the Moon. We usually think of the limb of the Moon as a smooth curve, but it’s actually jagged. What you may see is Aldebaran wink in and out as light shines down those lunar valleys and is alternately blocked out behind peaks and crater rims. This is an unforgettable sight, and makes for great video. A record of a grazing occultation by multiple observers can also be used to create a profile of the lunar limb. That light from Aldebaran took 65 years to get here, only to be blocked by our Moon at the very last second.

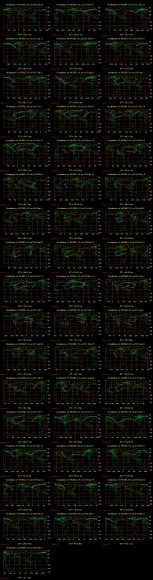

And observers (myself one of them) based in Europe shouldn’t count themselves out. Like brighter planets, you can spy a +1 magnitude star such as Aldebaran near the daytime Moon using binoculars or a telescope… if, of course, you have a high contrast deep blue sky and know exactly where to look for it. The International Occultation Timing Association has a page for the event with a complete list of ingress and egress times for key cities on three continents in the path. We’ll be watching the Wednesday event – clear skies willing — from our present basecamp in the Andalusian foothills just outside of Jimena de la Frontera, Spain.

During our current epoch, the Moon can only occult four +1st magnitude stars: Regulus, Spica, Antares and Aldebaran. The slow motion movement of the Moon, the Earth and the background stars make this prestigious A-list change over time: until about two millennia ago, you could also count the bright star Pollux in Gemini among them.

In the current century, (2001-2100 AD) the Moon occults Aldebaran 247 times, topped only by Antares (386 times) and barely beating out Spica (220 times).

Timing an occultation is fun and as easy as shooting video of the Moon through a telescope at the appointed time of ingress or egress. Practice on framing the dazzling Moon first well in advance — probably the toughest part is getting the exposure of the bright limb stopped down enough to still see and image the star. We find that shooting anywhere from 1/100th to 1/500th frame rate for a gibbous Moon is about right. Don’t be afraid to crank up the magnification a bit, so you can place the bulk of the Moon out of view. Also, catching occultations of stars and planets during waning Moon phases are more challenging than waxing, as the star will ingress behind the bright leading limb and later reappear behind the dark trailing limb (waxing is vice versa).

Observing: Running an audible time hack in the background such as WWV radio out of Fort Collins, Colorado can provide a precise record of the occultation.

But wait, there’s more. When the Moon occults Aldebaran, its also crossing the background V-shaped open star cluster known as the Hyades. Worldwide the waning gibbous Moon also occults Gamma, 51, and Theta^1 and Theta^2, SAO 93975, and 119 Tauri. Chances are, there’s an occultation for YOU to catch this week, regardless of your location.

Want more? Well, the Moon continues to occult Aldebaran every lunation through 2017, and will also start a cycle of passes in front of Regulus on December 18th. In fact, the next occultation of Aldebaran on November 15th favors central Asia, and the event two lunations from now on December 13th brings the path back around the North America.

A great close out for 2016, for sure. Don’t miss this week’s occultation!