Turns out it’s all a big cosmic blame game.

Over the centuries, humans have attempted to link the phases of the Moon—especially the onset of the Full Moon—with terrestrial affairs. Heck, terms such as lunacy have even entered into the common lexicon, citing a supposed connection between insanity brought on by the Moon. And we’ve long heard anecdotal tales from police and late shift delivery room workers, who swear that everything, from crime rates to delivery room admissions increase around a Full Moon.

A 2004 study published in a nursing journal looking at admissions in a hospital in Barcelona, Spain cited a similar phenomenon.

So, what is this lunacy?

A recent study out of the UCLA caught our eye addressing this same issue. UCLA professor of planetary astronomy Jean-Luc Margot took a fresh look at the data from the 2004 study and found not only flaws in the correlation and data analysis in the 2004 study, but no link between the onset of the Full Moon and a spike in hospital admissions. We agree that looking at one hospital unit in Barcelona hardly constitutes a large data set. This also backs up a larger 40 year-old UCLA meta-study which found no correlation between the timing of births and the lunar cycle.

“The Moon is innocent,” Margot said, exonerating our celestial companion in a UCLA press release.

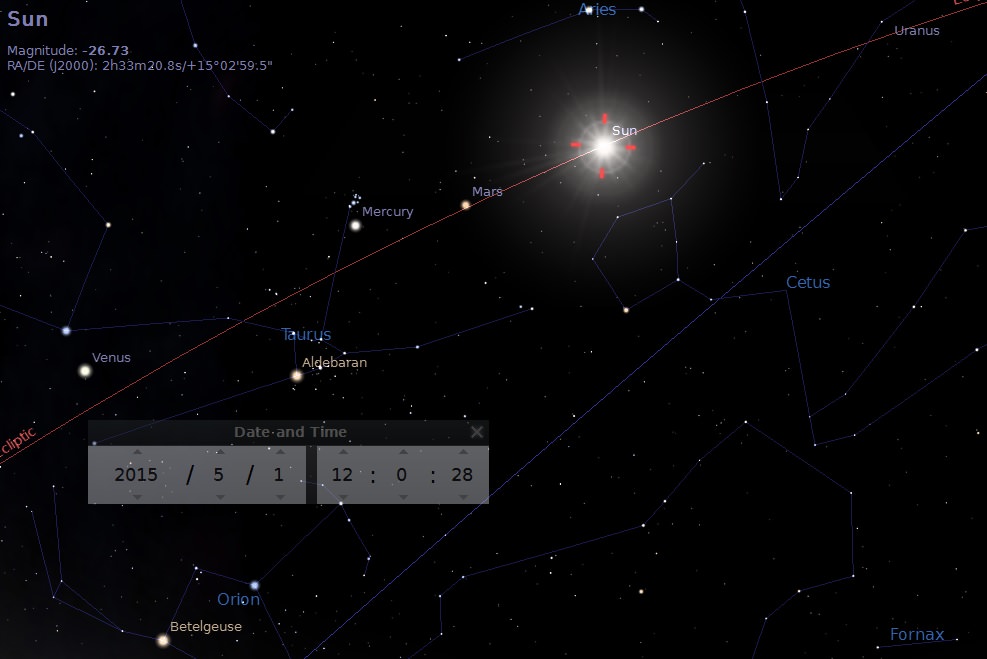

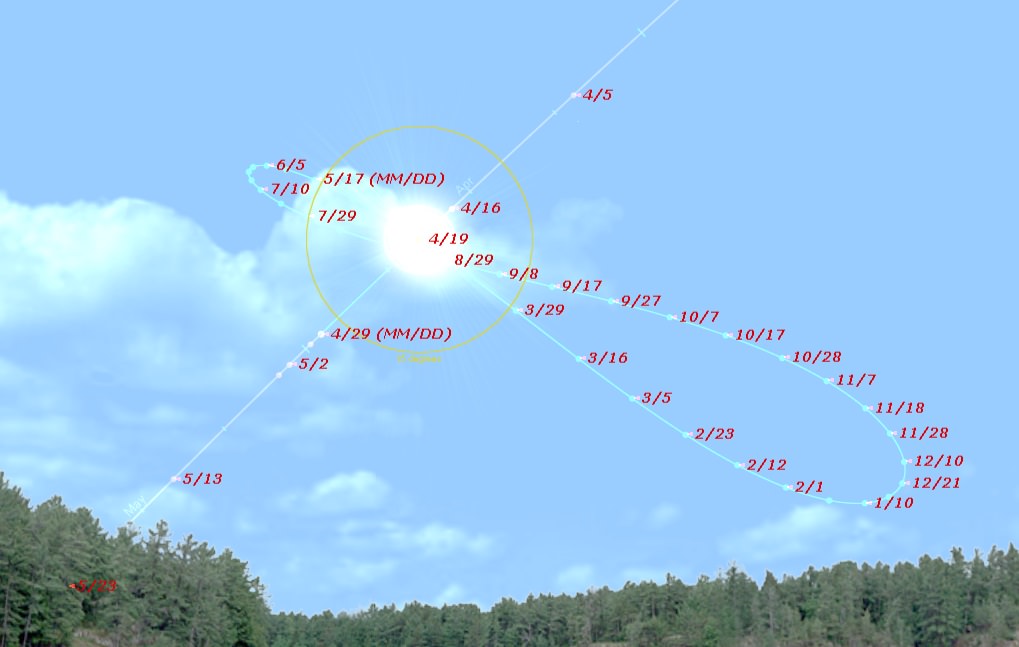

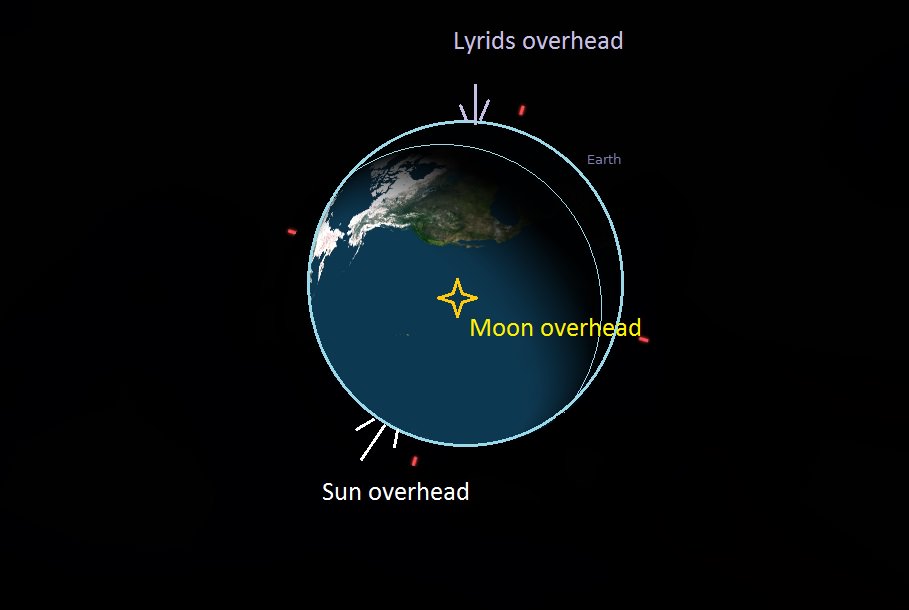

Blame our good friend and logical fallacy confirmation bias. Also known as the gambler’s fallacy, this occurs when we tend to count the hits but not the misses. When a topic such as a link between the Full Moon and a given activity comes up, we search back in our memory—which in and of itself is much more frangible than we’d like to think—and selectively remember all of the times that a Full Moon occurred when (pick your stated bias) occurred. And keep in mind, a Full Moon is only the technical instant when the Moon is opposite to the Sun and merely appears fully illuminated as seen from our Earthly perspective. That’s 180 degrees solar elongation, if you want to be precise. Of course, the orbit of the Moon is tilted about 5 degrees relative to the ecliptic, meaning that it’s only precisely opposite to the Sun during a central total lunar eclipse, when it’s immersed in the shadow of the Earth. Though the Moon approaches it, it never really reaches 100% illumination as seen from the Earth!

So much for werewolves…

The Moon also appears pretty darned close to Full on days it isn’t on the dates surrounding this instant in time. We say the Moon is then either waxing gibbous (headed towards Full) or waning gibbous (after Full).

Here’s what the Full Moon doesn’t do, though we’ve heard ‘em all over the years: Increase birth rates, criminal activity, cause an increase in car accidents, cause a spike in earthquake activity, or affect fishing expedition outcomes. Well, OK, you might have more success finding your way back to shore using the moonlight as a guide if you stay out after dark…

A 2013 Swiss study in the journal of Current Biology has suggested a possible link between lunar and human sleep cycles, though again, this is very tentative. (thanks to K.E.M Lindblom @the_egghunter on Twitter for bringing this one to our attention.)

Update: Astronomer Jean-Luc Margot has brought it the attention of Universe Today that said lunar sleep study has been debunked last year.

So, what does the Moon do? Well, for one, it does a great job stabilizing the Earth’s rotational axis over the long term. One only has the look at moonless Mars (for the sake of this discussion, the tiny captured asteroids Phobos and Deimos do not count) to see what variations in the axial tilt of our world would be like without the Moon. And certain species of sea turtles along the Florida Gulf Coast do, in fact, hatch right around the time on the spring Full Moon. The Moon also provides us with a nifty celestial timekeeper: a good example is the Muslim calendar, which is based solely on the cycle of the Moon. The Full Moon also provided the human species with a fine study of celestial mechanics 101. Newton would’ve had a much tougher prospect figuring out his laws of gravity in its absence.

And finally, the Full Moon does affect the migratory patterns of deep sky astrophotographers, as they ‘pack it in’ in the weeks around the light polluting Full Moon, perchance to process and clean up images.. .

All thoughts to ponder on the next Full Moon, which occurs on June 2nd… at 16:22 UT/12:22 AM EDT, to be precise.

So, as with all things that arc towards the astrological, we’ll defer to Shakespeare, who said, “The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars… but in ourselves. “

What other wacky lunar tie-ins have you heard of?