It’s a dangerous universe out there, for a budding young space-faring species.

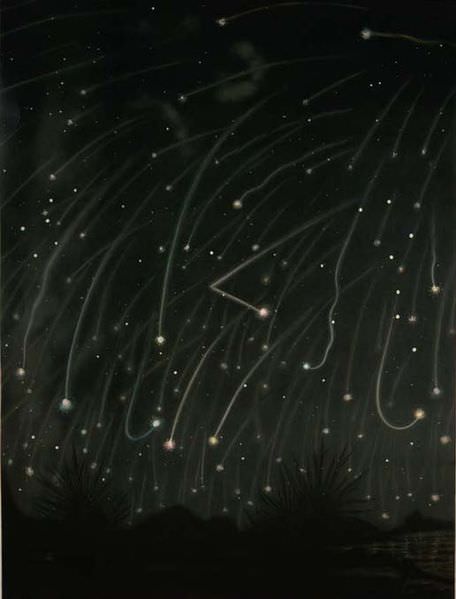

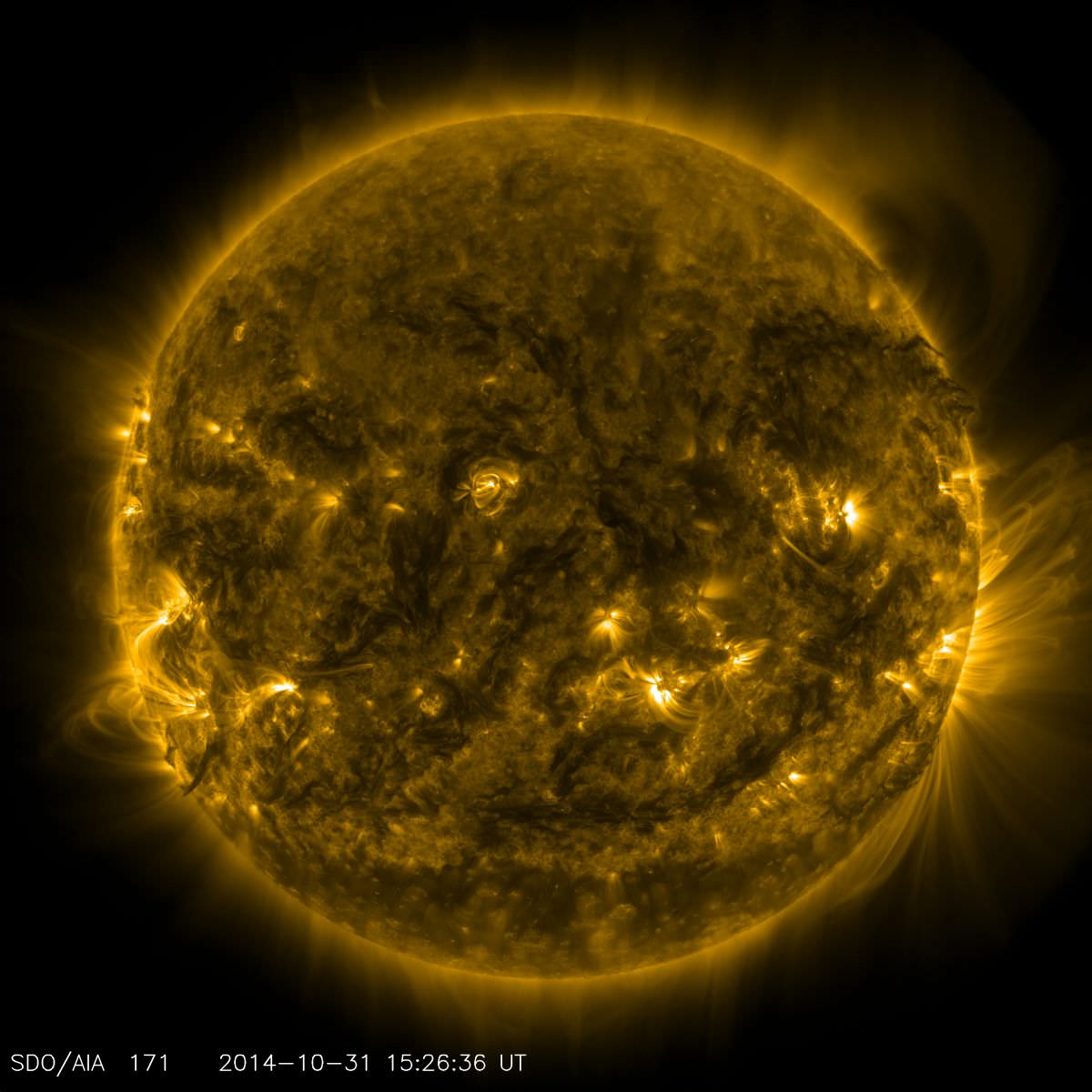

Killer comets, planet sterilizing gamma ray bursts, and death rocks from above are all potential hazards that an adolescent civilization has to watch out for.

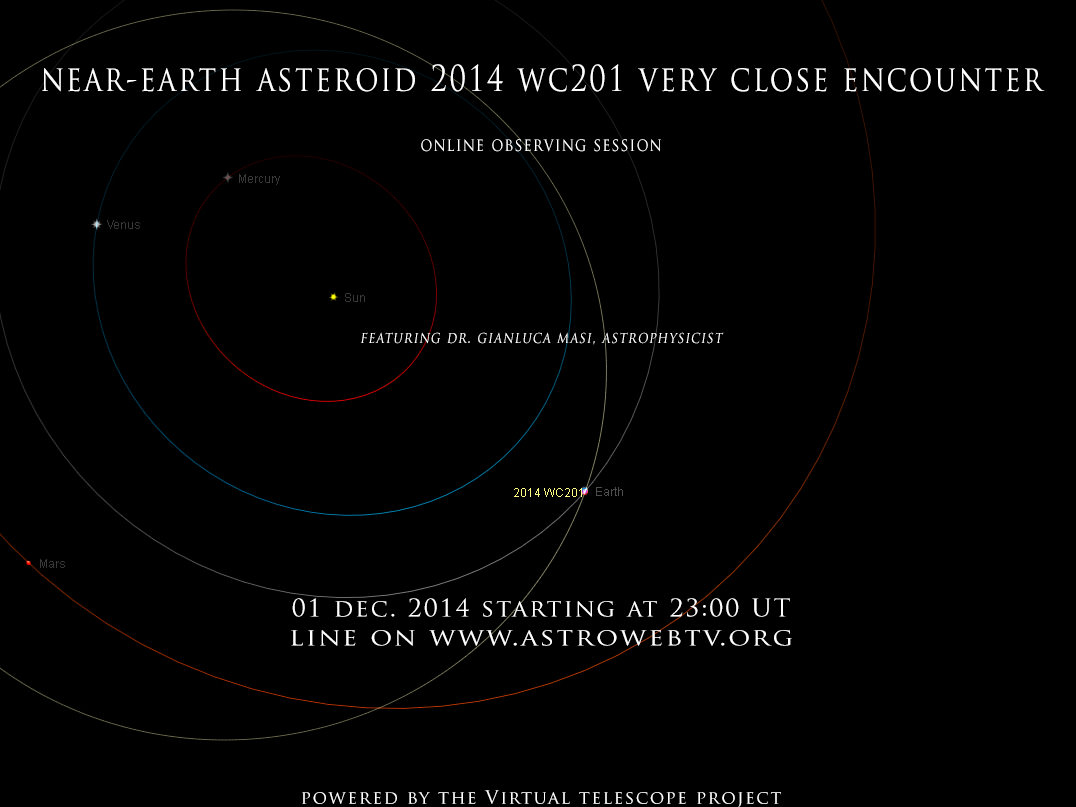

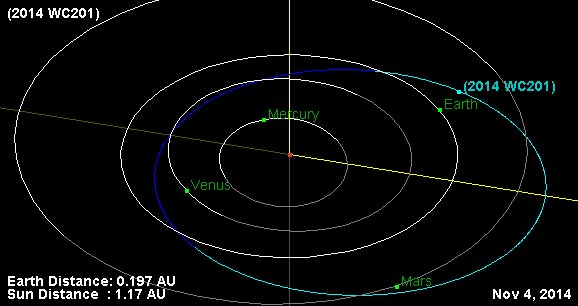

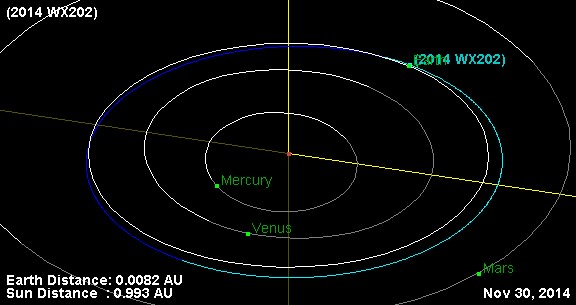

This week offers two close shaves, as newly discovered Near Earth Asteroids (NEAs) 2014 WC201 and 2014 WX202 pass by the Earth-Moon system.

The passage of 2014 WC201 is coming right up tonight, as the 27-metre space rock passes about 570,000 kilometres from the Earth. That’s 1.4 times farther than the distance from the Earth to the Moon.

And the good news is, the Virtual Telescope Project will be bringing the passage of 2014 WC201 live tonight starting at 23:00 Universal Time/6:00 PM EST.

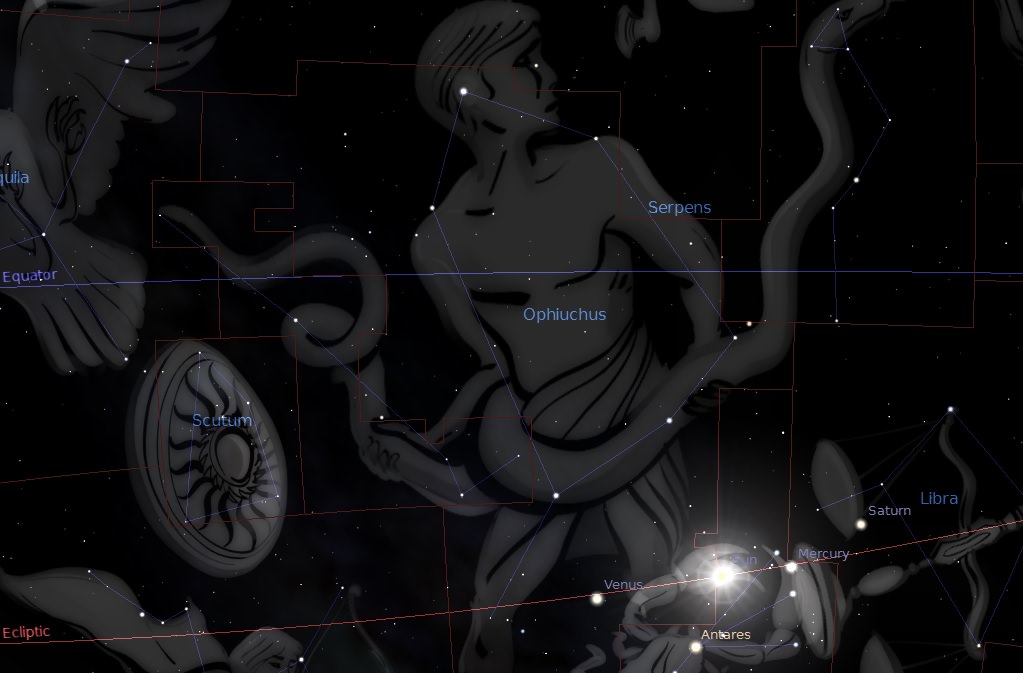

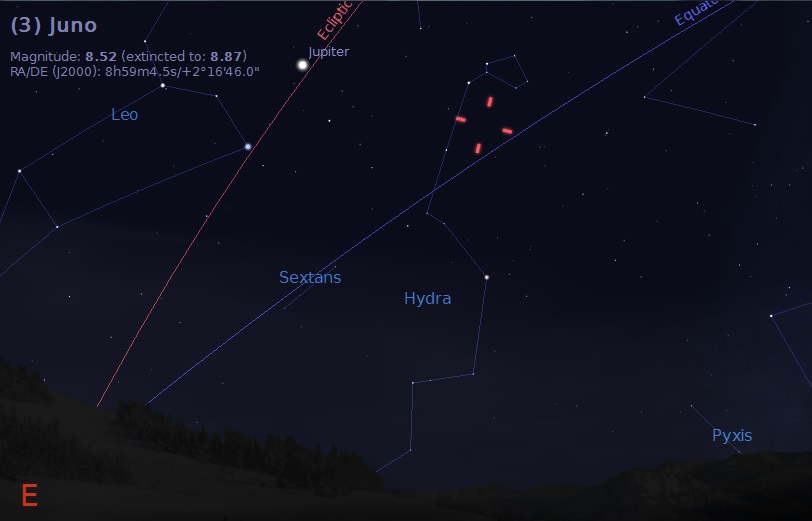

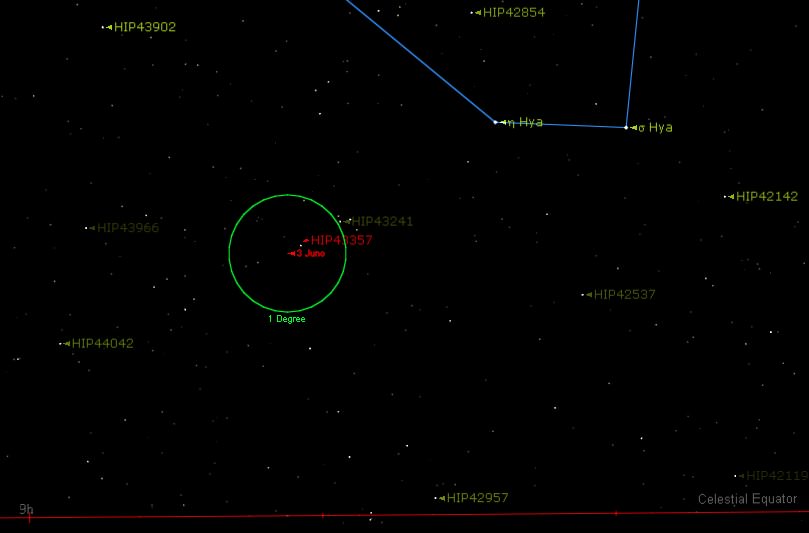

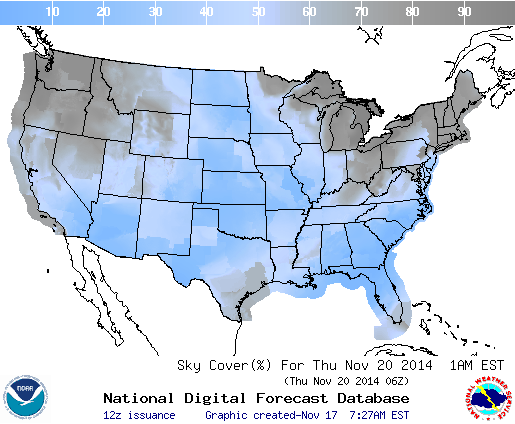

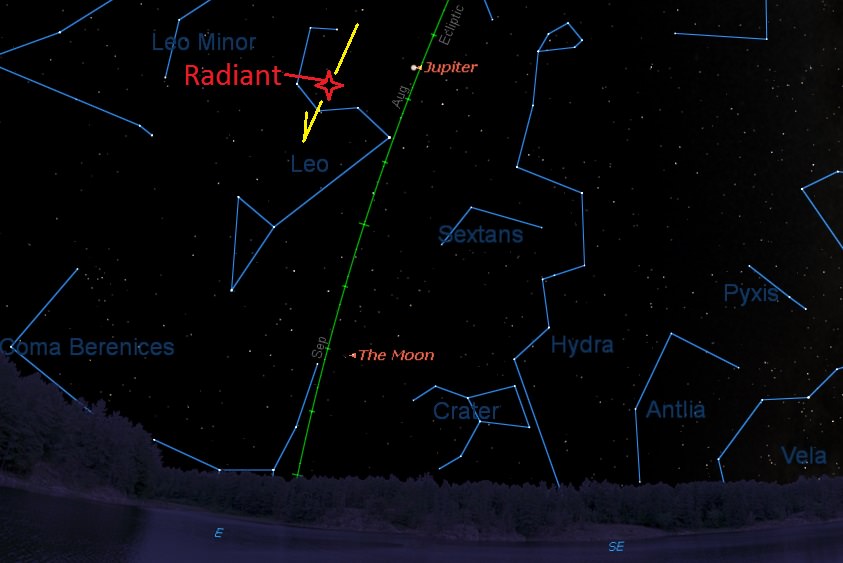

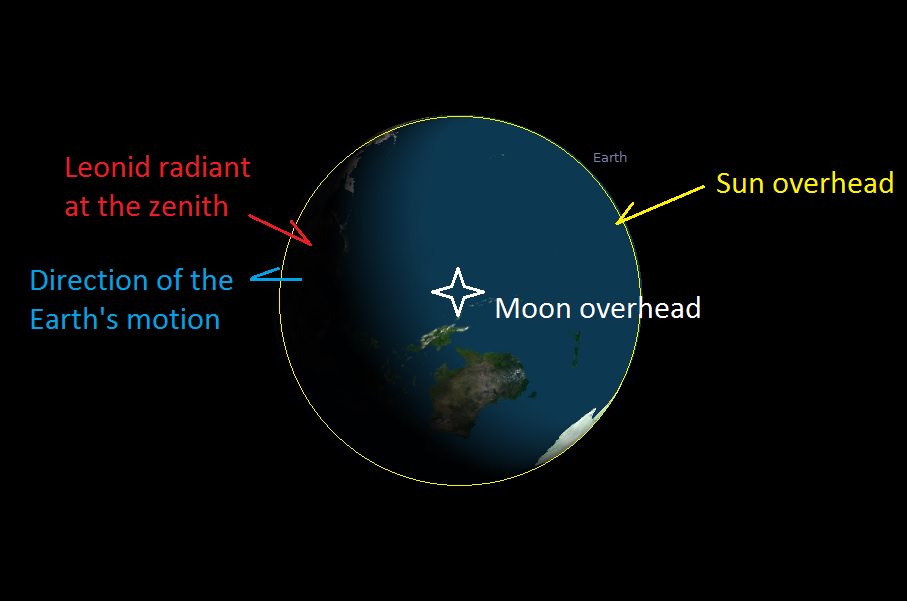

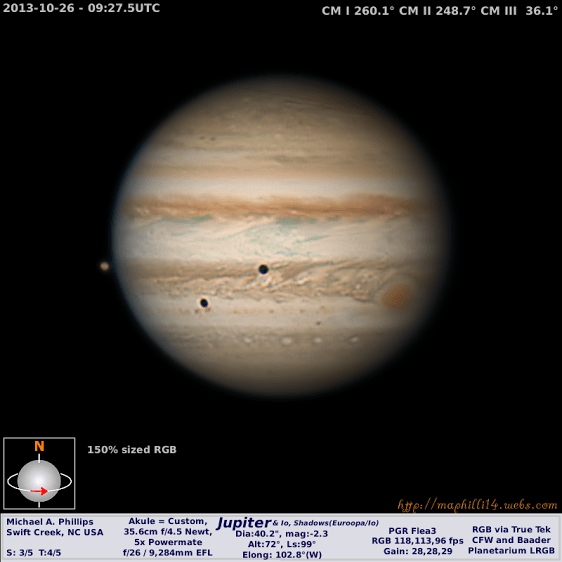

Shining at an absolute magnitude of +26, 2014 WC201 will be visible as a +13 apparent magnitude “star” at closest approach at 4:51 UT (December 2nd)/11:51 PM EST (December 1st) moving through the constellation Ursa Major. This puts it within range of a large backyard telescope, though the 80% illuminated waxing gibbous Moon will definitely be a mitigating factor for observation.

The JPL Horizons ephemerides generator is an excellent place to start for crafting accurate coordinates for the asteroid for your location.

At an estimated 27 metres/81 feet in size, 2014 WC201 will no doubt draw “house-sized” or “building-sized” comparisons in the press. Larger than an F-15 jet fighter, asteroids such as WC201 cry out for some fresh new descriptive comparisons. Perhaps, as we near a “Star Wars year” in 2015, we could refer to 2014 WC201 as X-wing sized?

Another Apollo NEO also makes a close pass by the Earth this week, as 6-metre 2014 WX202 passes 400,000 kilometres (about the same average distance as the Earth to the Moon) from us at 19:56 UT/2:56 PM EST on December 7th. Though closer than WC201, WX202 is much smaller and won’t be a good target for backyard scopes. Gianluca Masi over at the Virtual Telescope Project also notes that WX202 will also be a difficult target due to the nearly Full Moon later this week.

The last Full Moon of 2014 occurs on December 6th at 6:26 AM EST/11:26 Universal Time.

2014 WX202 has also generated some interest in the minor planet community due to its low velocity approach relative to the Earth. This, coupled with its Earth-like orbit, is suggestive of something that may have escaped the Earth-Moon system. Could WX202 be returning space junk or lunar ejecta? It’s happened before, as old Apollo hardware and boosters from China’s Chang’e missions have been initially identified as Near Earth Asteroids.

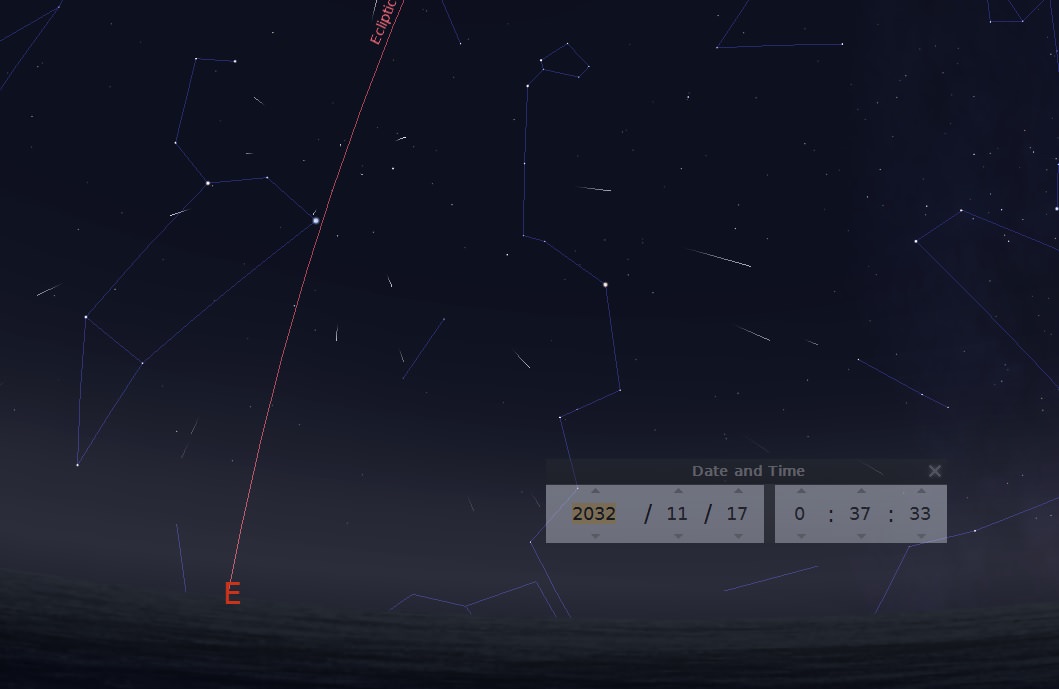

The Earth also occasionally hosts a temporary “quasi-moon,” as last occurred in 2006 with the capture of RH120. 2014 WX202 makes a series of more distant passes in the 2030s, and perhaps it will make the short list of near Earth asteroids for humans to explore in the coming decades.

And speaking of which, humanity is making two steps in this direction this week, with two high profile space launches.

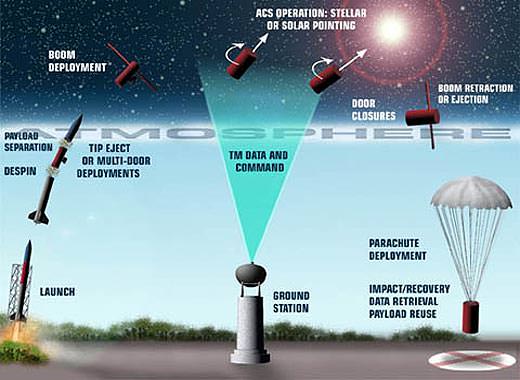

First up is the launch of JAXA’s Hayabusa 2 from the Tanegashima Space Center on December 3rd at 4:22 UT/11:22 PM EST. The follow up to the Hayabusa asteroid sample return mission, Hayabusa 2 will rendezvous with asteroid 1999 JU3 in 2018 and return samples to Earth in late 2020. The vidcast for the launch of Hayabusa 2 goes live at 3:00 UT/10:00 PM EST on Tuesday, December 2nd.

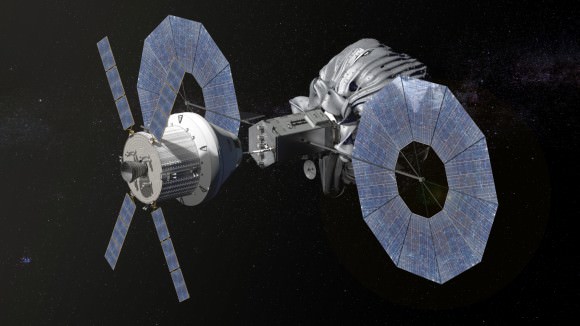

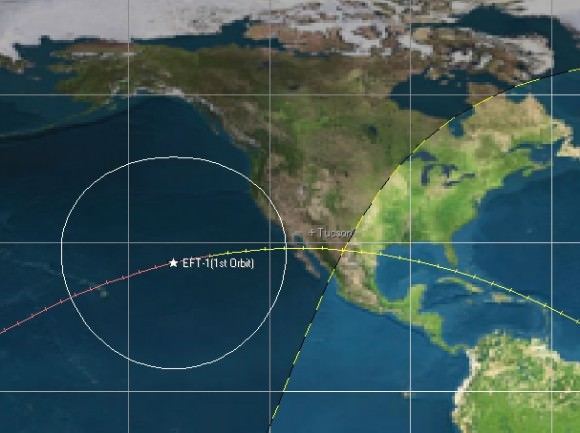

And the next mission paving the way towards first boot prints on an asteroid is the launch of a Delta 4 Heavy rocket with EFT-1 from Cape Canaveral this Thursday morning on December 4th near sunrise at 7:05 AM EST/12:05 UT. EFT-1 is uncrewed, and will test key technologies including reentry on its two orbit flight. Expect to see crewed missions of Orion to begin around 2020, with a mission to an Earth crossing asteroid sometime in the decade after that.

And there are some decent prospects to catch sight of EFT-1 on its first pass prior to its orbit raising burn over the Atlantic. Assuming EFT-1 lifts off at the beginning of its launch window, western Australia may see a good dusk pass 55 minutes after liftoff, and the southwestern U.S. may see a visible pass at dawn about 95 minutes after EFT-1 leaves the pad.

We’ll be tracking these prospects as the mission evolves on launch day via Twitter, and NASA TV will carry the launch live starting at 4:30 AM EST/9:30 UT.

The Orion capsule will come in hot on reentry at a blistering 32,000 kilometres per hour over four hours after liftoff in a reentry reminiscent of the early Apollo era.

Of course, if an asteroid the size of WC201 was on a collision course with the Earth it could spell a very bad day, at least in local terms. For comparison, the 2013 Chelyabinsk meteor was estimated to be 18 metres in size, and the 1908 Tunguska impactor was estimated to be 60 metres across. And about 50,000 years ago, a 50 metre in diameter space rock came blazing in over the ponderosa pine trees near what would one day be the city of Flagstaff, Arizona to create the 1,200 metre diameter Barringer Meteor Crater you can visit today.

All the more reason to study hazardous space rocks and the technology needed to reach one in the event that we one day need to move one out of the way!