Time to dust off those ‘what is a perigee Full Moon’ explainer posts… the supermoon once again cometh this weekend to a sky near you.

Yes. One. More. Time.

We’ve written many, many times — as have many astronomy writers — about the meme that just won’t die. The supermoon really brings ‘em out, just like werewolves of yore… some will groan, some will bemoan the use of a modernized term inserted into the common astronomical vernacular that was wrought by an astrologer, while others will exclaim that this will indeed be the largest Full Moon EVER…

But hey, it’s a great chance to explain the weird and wonderful motion of our nearest natural neighbor in space. Thanks to the Moon, those astronomers of yore had some great lessons in celestial mechanics 101. Without the Moon, it would’ve been much tougher to unravel the rules of gravity that we take for granted when we fling a probe spaceward.

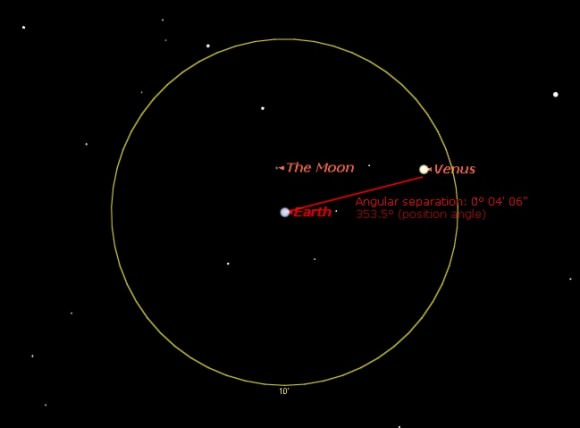

The Moon reaches Full on Tuesday, September 9th at 1:38 Universal Time (UT), which is 9:38 PM EDT on the evening of the 8th. The Moon reaches perigee at less than 24 hours prior on September 8th at 3:30 UT — 22 hours and 8 minutes earlier, to be precise — at a distance 358,387 kilometres distant. This is less than 2,000 kilometres from the closest perigee than can occur, and 1,491 kilometres farther away than last month’s closest perigee of the year, which occurred 27 minutes prior to Full Moon.

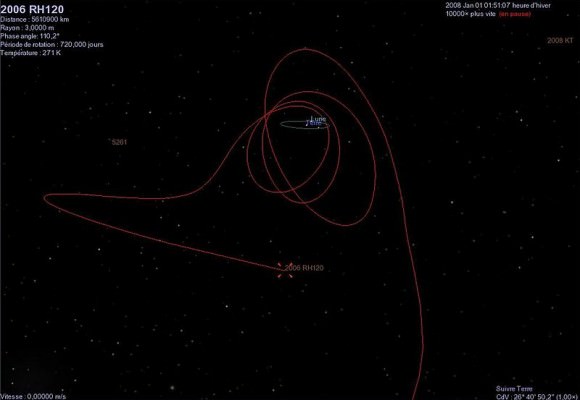

A Proxigean or Perigee Full “Supermoon” as reckoned by our preferred handy definition of “a Full Moon occurring within 24 hours of perigee” generally occurs annually in a cycle of three over two lunar synodic periods, and moves slowly forward by just shy of a month through the Gregorian calendar per year. The next cycle of “supermoons” starts on August 30th, 2015, and you can see our entire list of cycles out through 2020 here.

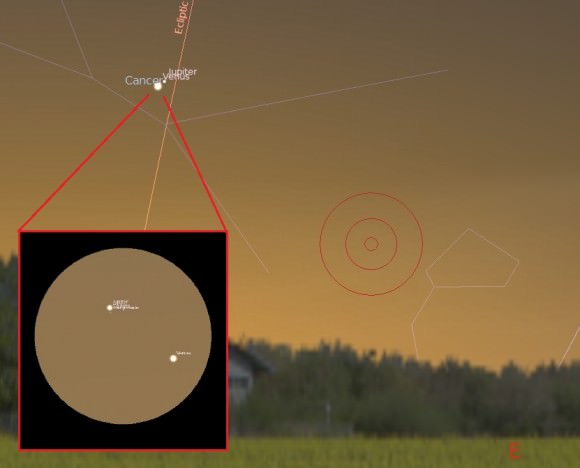

What’s the upshot of all this? Well, aside from cluttering inboxes and social media with tales of the impending supermoon this weekend, the rising Moon will appear 33.5’ arc minutes in diameter as opposed to its usually quoted average of 30’ in size. And remember, that’s in apparent size as seen from our Earthly vantage point… can you spy a difference from one Full Moon to the next? Fun fact: the rising Moon is actually farther away from you to the tune of about one Earth radius than when it’s directly overhead at the zenith.

Fed up with supermoon-mania? The September Full Moon also has a more pedestrian name: The Harvest Moon. Actually, this is the Full Moon that falls nearest to the September Equinox, marking the start of the astronomical season of Fall in the northern hemisphere and Spring in the southern. In the current first half of the 21st century, the September Equinox falls on the 22nd or 23rd, meaning that the closest Full Moon (and thus the Harvest Moon) can sometimes fall in October, as last happened in 2009 and will occur again in 2017. In this instance, the September Full Moon would then be referred to as the Corn Moon as reckoned by the Algonquins, and is occasionally referred to as the Drying Grass Moon by Sioux tribes. In 2014, the Harvest Full Moon “misses” falling in October by about 32 hours!

So, why is it known as the Harvest Moon? Well, in the age before artificial lighting (and artificial light pollution) the rising of the Full Moon as the Sun sets allowed for a few hours of extra illumination to bring in crops. In October, the same phenomenon gave hunters a few extra hours to track game by the light of the Full Hunters Moon, both essential survival activities before the onset of the long winter.

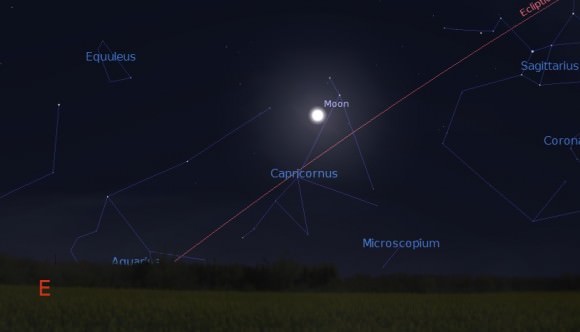

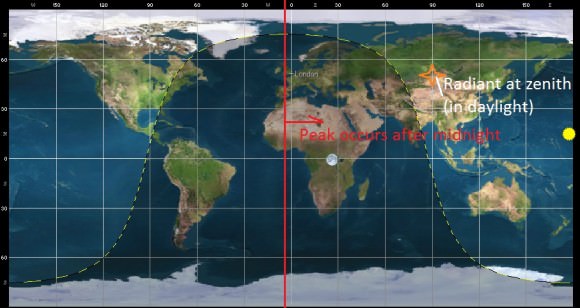

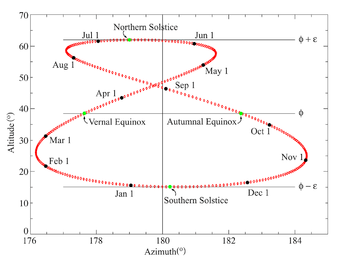

And that Full Harvest Moon seems to “stick around” on successive evenings. This is due to the relatively shallow angle of the evening ecliptic to the eastern horizon as seen from mid-northern latitudes in September.

Here’s a sample of rising times for the Moon this month as seen from Baltimore, Maryland at 39.3 degrees north latitude:

Saturday, September 6th: 5:43 PM EDT

Sunday, September 7th: 6:23 PM EDT

Monday, September 8th: 7:05 PM EDT

Tuesday, September 9th: 7:44 PM EDT

Wednesday, September 10th: 8:22 PM EDT

Note the Moon rises only ~40 minutes later on each successive evening.

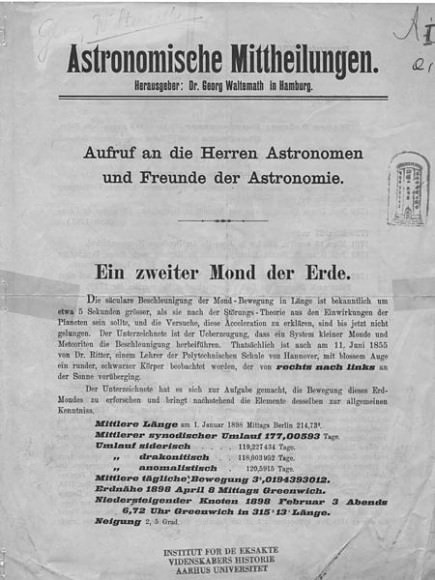

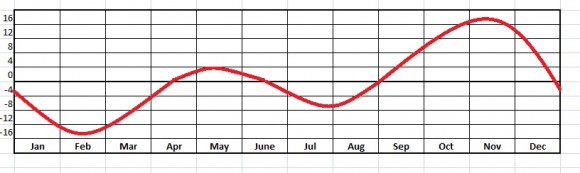

We’re also headed towards a “shallow year” in 2015, as the Moon bottoms out relative to the ecliptic and only ventures 18 degrees 20’ north and south of the celestial equator at shallow minimum. This is due to what’s known as the Precession of the Line of Apsides as the gravitational pull of the Sun slowly drags the orbit of the Moon round the earth once every 8.85 years. The nodes where the ecliptic and path of the Moon meet — and solar and lunar eclipses occur — also move slowly in an opposite direction of the Moon’s motion, taking just over twice as long as the Precession of the Line of Apsides to complete one revolution around the ecliptic at 18.6 years. This is one of the more bizarre facts about the motion of the Moon: its orbital tilt of 5.1 degrees is actually fixed with respect to the ecliptic as traced out by the Earth’s orbit about the Sun, not our rotational axis. Native American and ancient Northern European knew of this, and the next “Long Night’s Moon” also called a “Lunar Standstill” when the Moon rides high in the northern hemisphere sky is due through 2024-2025.

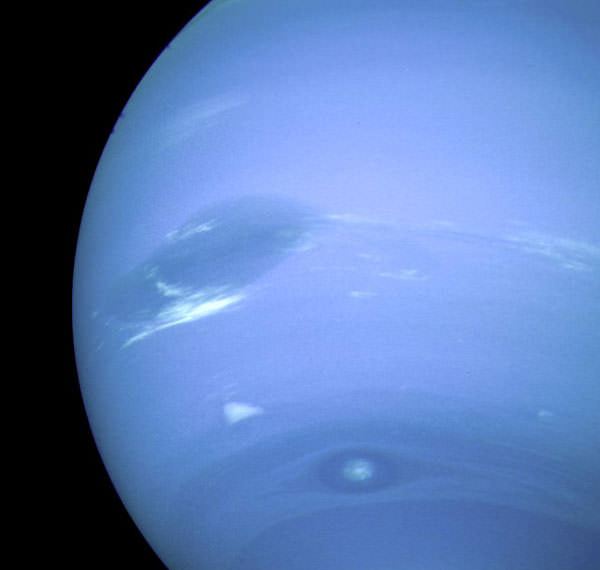

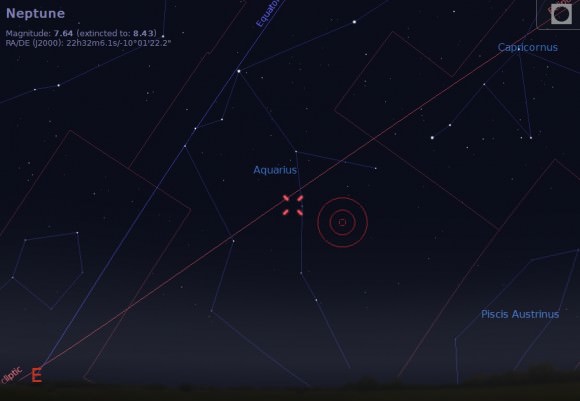

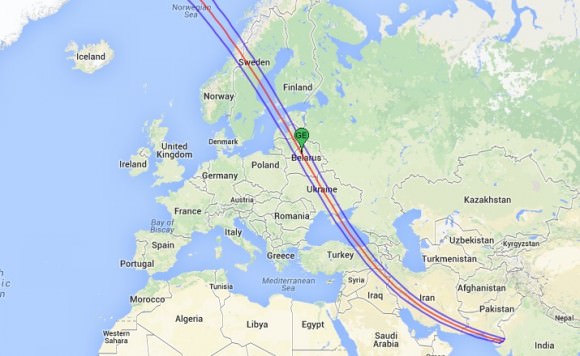

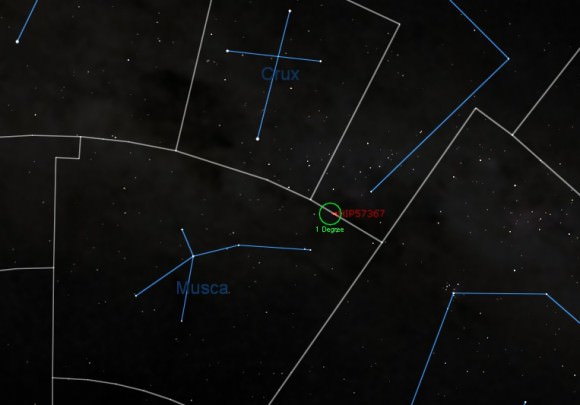

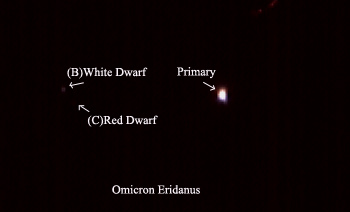

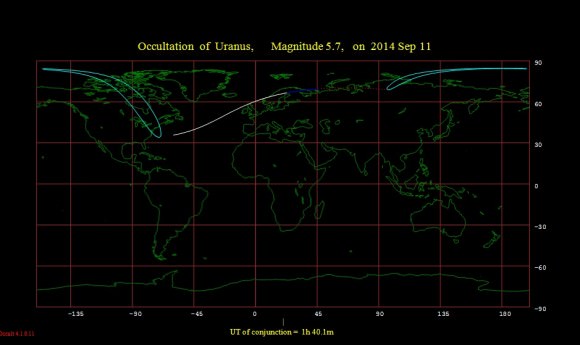

And to top it off, the Moon occults Uranus just two days after Full on September 11th as seen from northeastern North America, Greenland, Iceland and northern Scandinavia. We’re in a cycle of occultations of Uranus by the Moon from late 2014 through 2015, and this will set the ice giant up for a spectacular close pass, and a rare occultation of the planet for a remote region in the Arctic during the October 8th total lunar eclipse…

More to come!