If you do your own stargazing or participate in our Sunday night Virtual Star Parties, you’ve probably noticed we’re starting to lose planetary targets in the night-time sky. August and September of this year sees Venus and Saturn to the west at dusk, with the planets Mars and Jupiter adorning the eastern dawn sky just hours before sunrise.

That means there is now a good span of the night that none of the classic naked eye planets are above the horizon. But the good news is, with a little persistence, YOU can spy the outermost planet in our solar system in the coming weeks: the elusive Neptune. (Sorry, Pluto!)

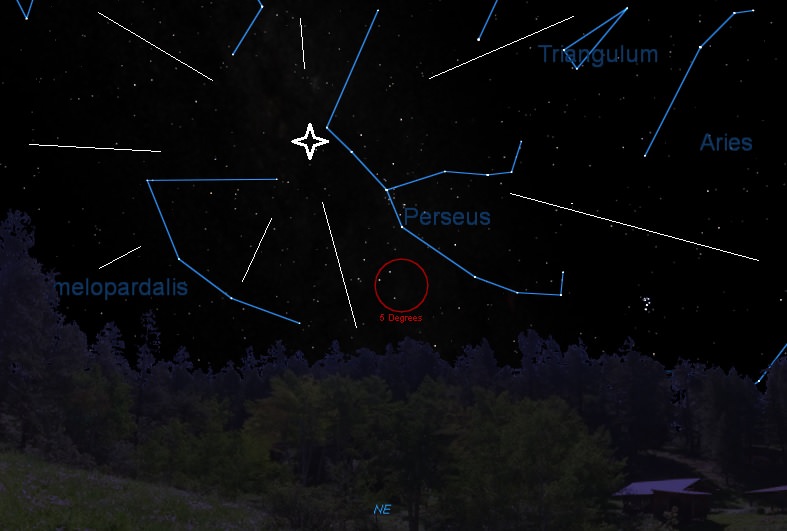

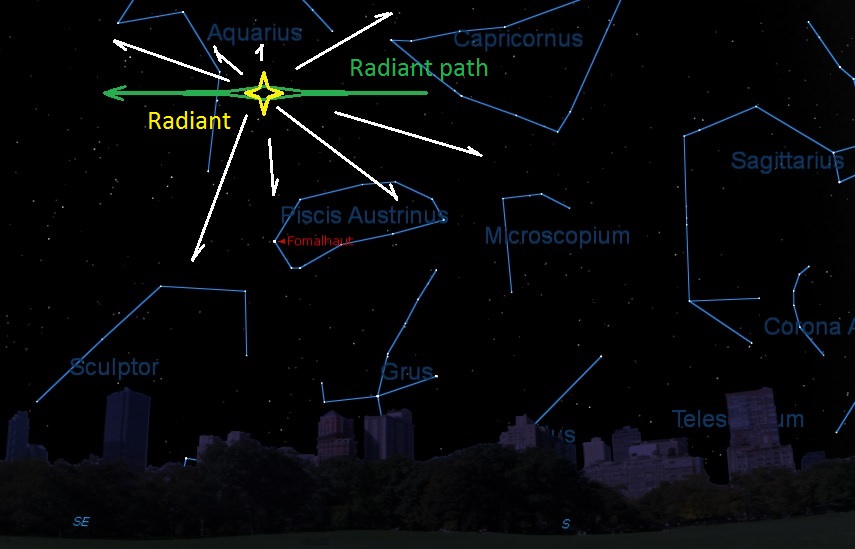

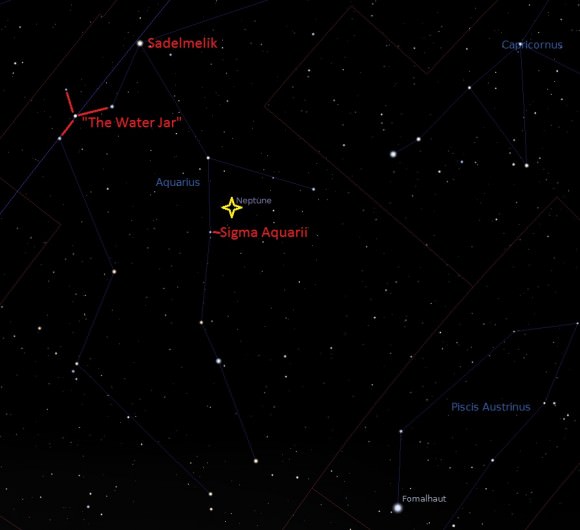

The planet Neptune reaches opposition late this month in the constellation Aquarius on August 27th at 01:00 UT (9:00 PM EDT on the 26th). This means that it will rise to the east as the Sun sets to the west and will remain above the local horizon for the entire night.

If you’ve never caught sight of Neptune, these next few weeks are a great time to try. The Moon passes 6° north of the planet’s location this week on August 21st, just 10 hours after reaching Full.

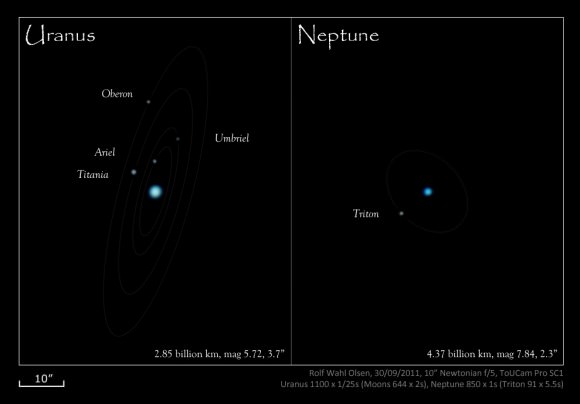

Shining at magnitude +7.8, Neptune is an easy catch with binoculars from a dark sky site. Even in a large telescope, Neptune appears as a tiny blue dot, almost looking like a dim planetary nebula that refuses to come to a sharp focus. Visually, Neptune is only 2.3” across at opposition; you could stack 782 Neptunes across the breadth of the Full Moon!

It’s sobering to think that Neptune only just returned in 2011 to the position of its original discovery back in 1846. The calculation of Neptune’s position by Urbain Le Verrier was a triumph for Newtonian mechanics, a moment where the science of astronomy began to demonstrate its predictive power.

Astronomers knew of the existence of an unseen body due to the perturbations of the planet Uranus, which was discovered surreptitiously by William Herschel 65 years earlier. Using Le Verrier’s calculations, Johann Galle and Heinrich d’Arrest spied the planet on the night of September 23rd, 1846 using the Berlin observatory’s 9.6” refractor. Neptune was within a degree of the position described in Le Verrier’s prediction.

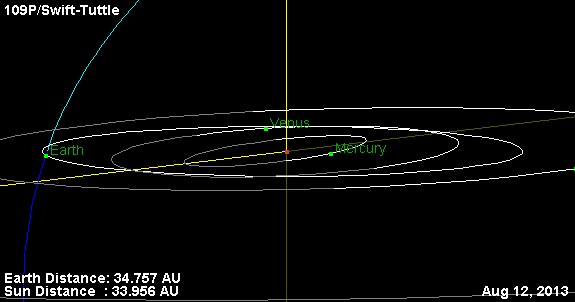

Neptune orbits the Sun once every 164.8 years, and comes back into opposition once every successive calendar year about 2 days later than the last. Those observers of yore were lucky that Neptune and Uranus experienced a close and undocumented conjunction in 1821; otherwise, Neptune may have gone undetected for a much longer span of time. And ironically, Galileo sketched the motion of Neptune near Jupiter in 1612 and 1613, but failed to identify it as a planet!

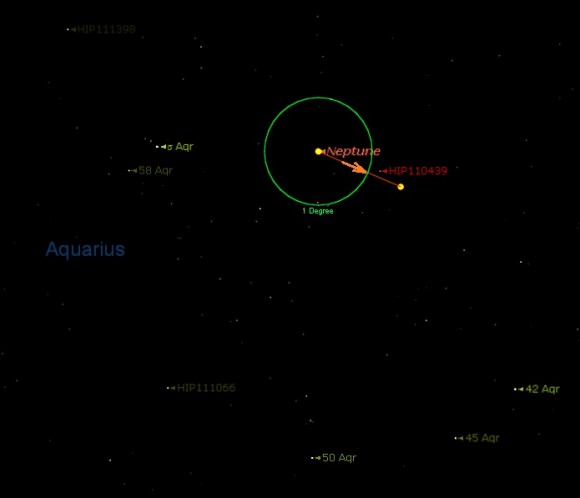

Neptune descended through the ecliptic in 2003 and won’t reach its southernmost point below it until 2045. This month, Neptune lies 1.5 degrees west of the +4.8 magnitude double star Sigma Aquarii. Neptune passes less than 4’ from +7.5 magnitude star HIP 110439 on September 9th as it continues towards eastern quadrature on November 24th.

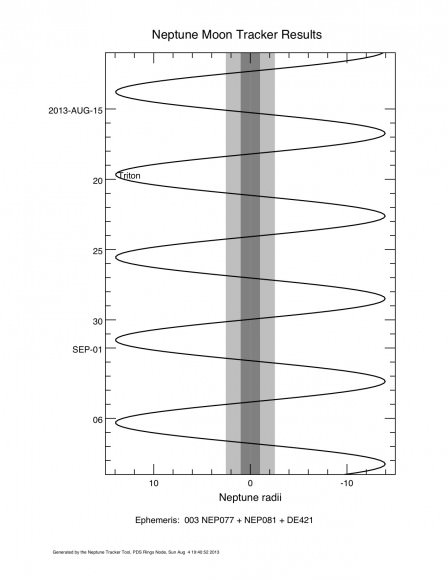

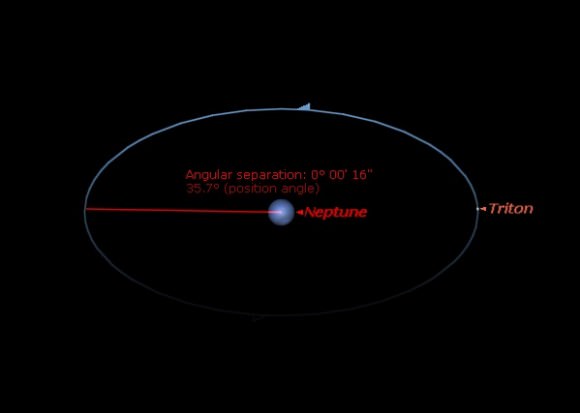

Up for a challenge? Neptune also has a large moon named Triton that is just within range of a moderate (8” in aperture or larger) telescope. Shining at magnitude +13.4, Triton is similar in brightness to Pluto and is 100 times fainter than Neptune. In fact, there’s some thought that Pluto may turn out to be similar to Triton in appearance when New Horizons gets a close-up look at it in July 2015.

Triton never strays more than 18” from Neptune during eastern or western elongations. This presents the best time to cross the moon off your astronomical “life list…” experienced amateurs have even managed to image Triton!

Triton was discovered just 17 days after Neptune by William Lassell using a 24” reflector. Triton is also an oddball among large moons in the solar system in that it’s in a retrograde orbit.

A second moon named Nereid was discovered by Gerard Kuiper in 1949. To date, Neptune has 14 moons, including the recently discovered S/2004 N1 unearthed in Hubble archival data.

To date, Voyager 2 is the only spacecraft that has studied Neptune and its moons up close. Voyager 2 conducted a flyby of the planet in 1989. A future mission to Neptune would face the same dilemma as New Horizons: a speedy journey would still take nearly a decade to complete, which would rule out an orbital insertion around the planet. (Darn you, orbital mechanics!) In fact, New Horizons just crosses the orbit of Neptune at a distance of 30 astronomical units from the Earth in 2014.

Neptune is about four light hours away from the Earth, a distance that varies less than 20 minutes in light travel time from solar conjunction to opposition. And while Neptune and Triton may not appear like much more than dim dots through a telescope, what you’re seeing is an ice giant 3.8 times the diameter of the Earth, with a large moon 78% the size of our own.

Make sure to cross Neptune and Triton off of your bucket list… and next month, we’ll be able to do the same for the upcoming opposition of Uranus!