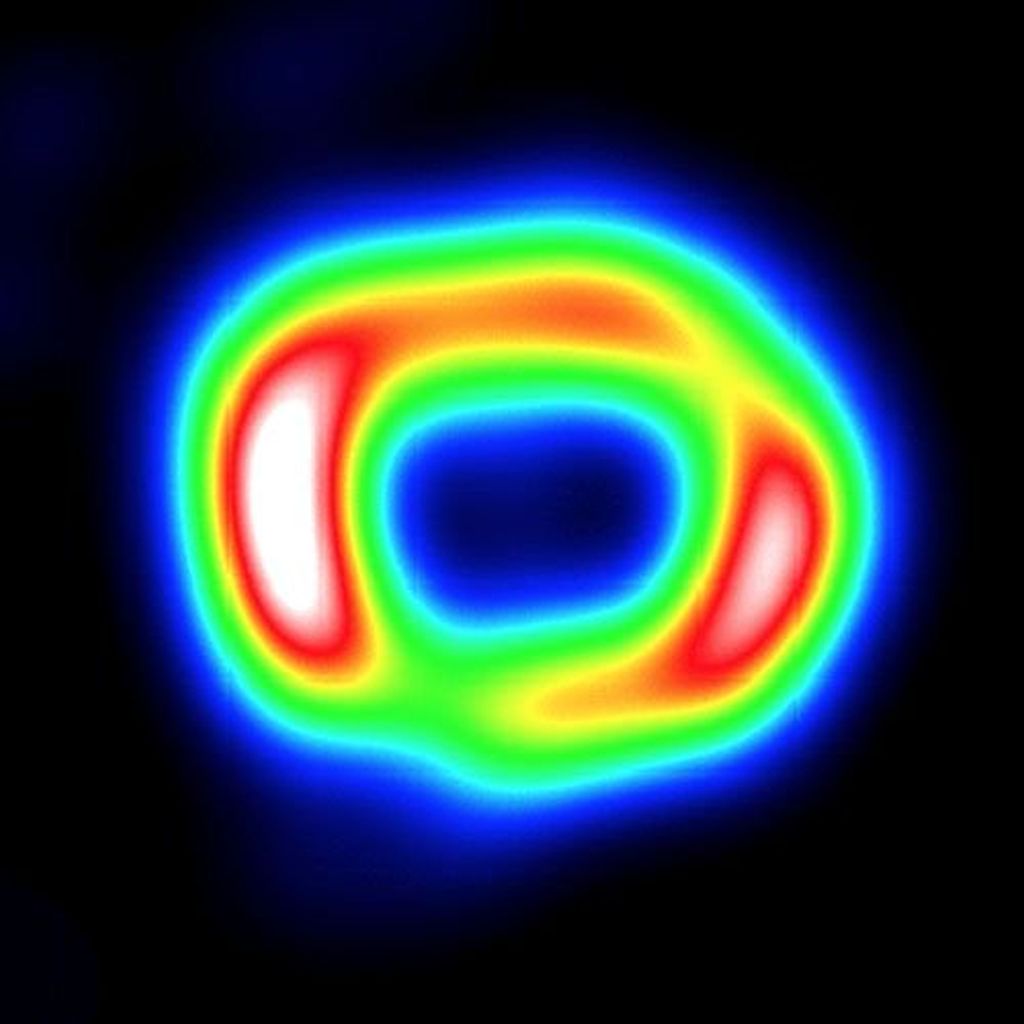

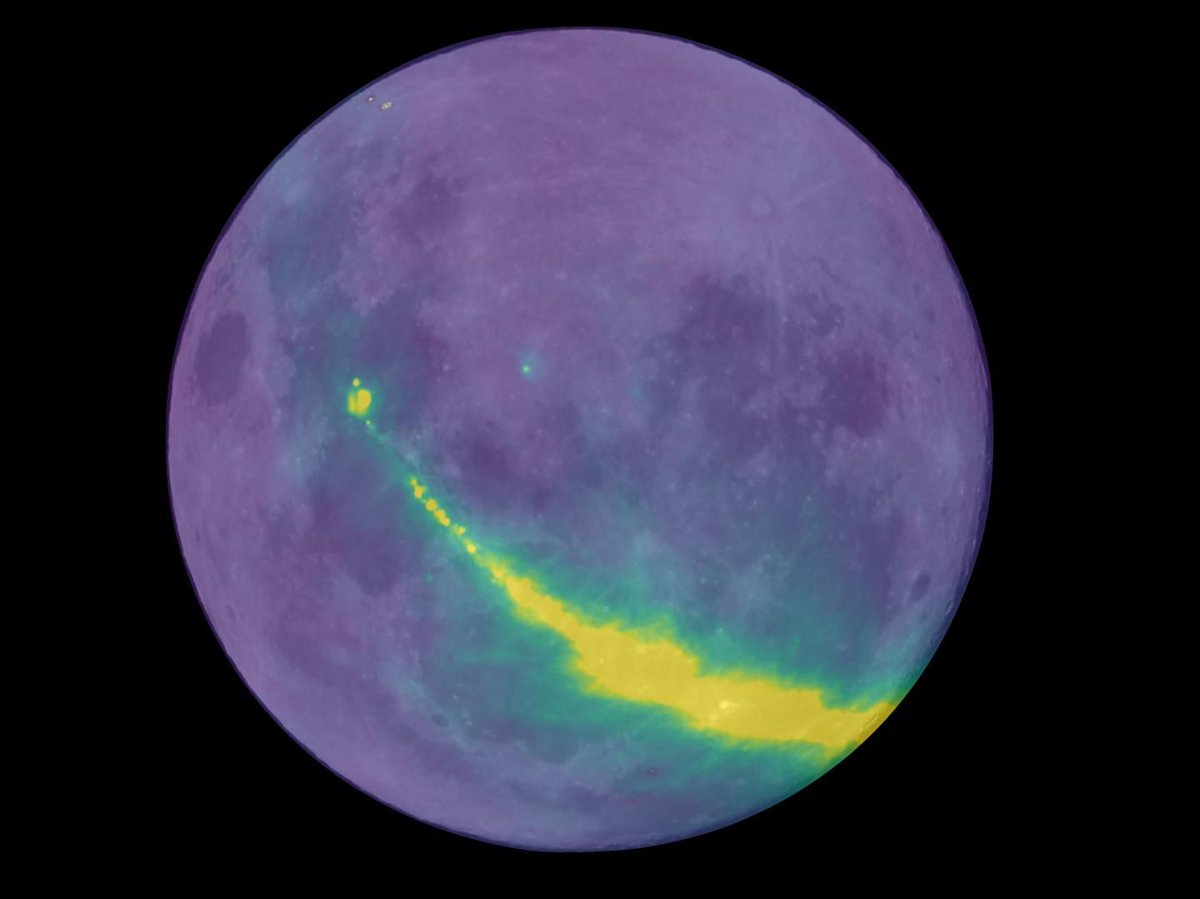

The ESA’s Mars Express orbiter has spotted a funny cloud on Mars, right near the Arsia Mons Volcano. At first glance it looks like a plume coming out of the volcano. But it’s formation is not related to any internal activity in this long-dead volcano. It’s a cloud of water ice known as an orographic or lee cloud.

The cloud isn’t linked to any volcanic activity, but its formation is associated with the form and altitude of Arsia Mons. Arsia Mons is a dormant volcano, with scientists putting its last eruptive activity at 10 mya. This isn’t the first time this type of cloud has been seen hovering around Arsia Mons.

Continue reading “There’s a Funny Cloud on Mars, Perched Right at the Arsia Mons Volcano. Don’t Get Too Excited, Though, it’s not an Eruption”