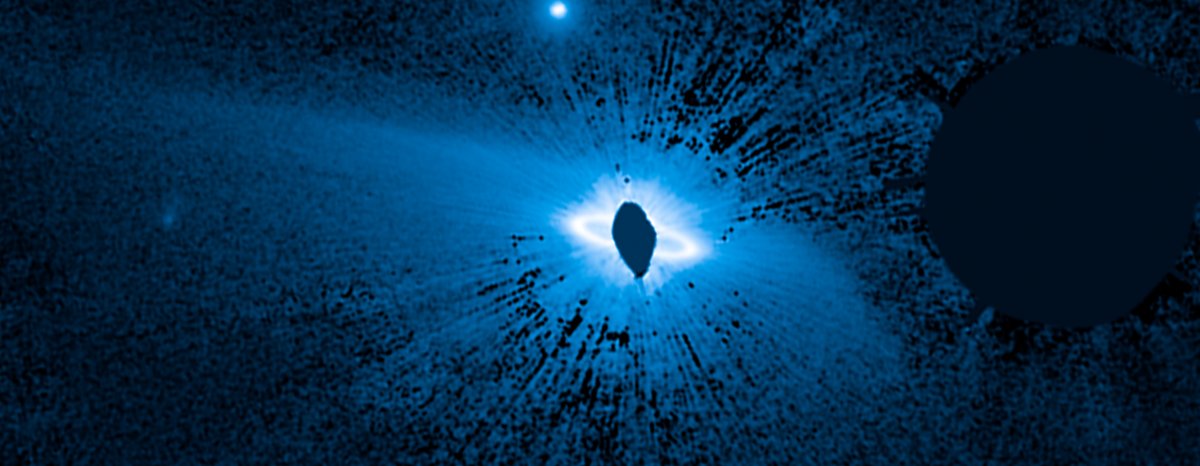

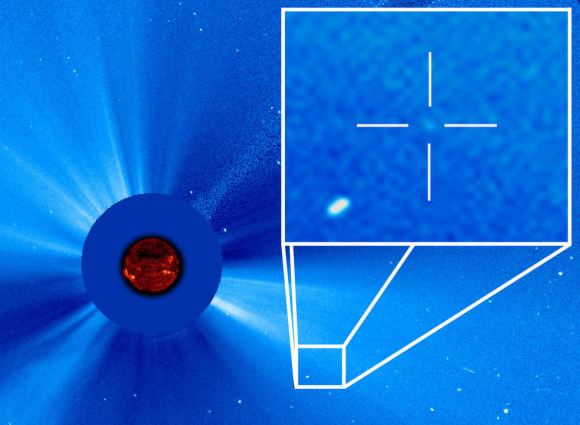

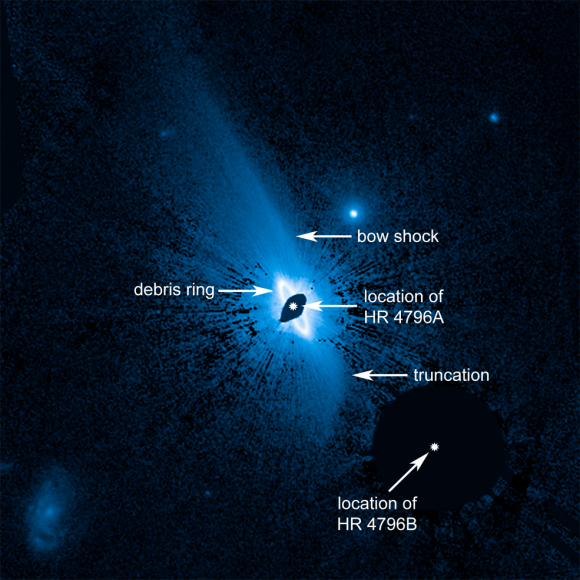

Younger stars have a cloud of dusty debris encircling them, called a circumstellar disk. This disk is material left over from the star’s formation, and it’s out of this material that planets form. But scientists using the Hubble have been studying an enormous dust structure some 150 billion miles across. Called an exo-ring, this newly imaged structure is much larger than a circumstellar disk, and the vast structure envelops the young star HR 4796A and its inner circumstellar disk.

Discovering a dust structure around a young star is not new, and the star in this new paper from Glenn Schneider of the University of Arizona is probably our most (and best) studied exoplanetary debris system. But Schneider’s paper, along with capturing this new enormous dust structure, seems to have uncovered some of the interplay between the bodies in the system that has previously been hidden.

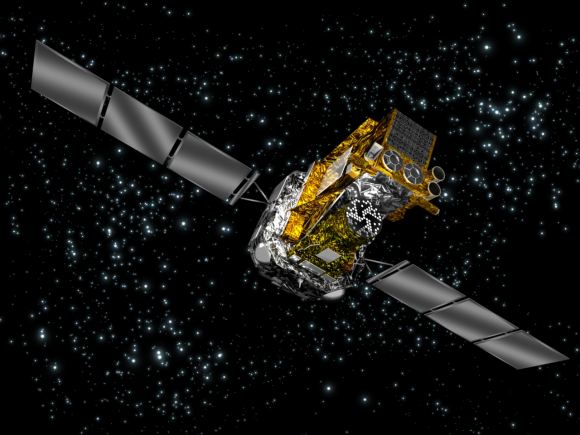

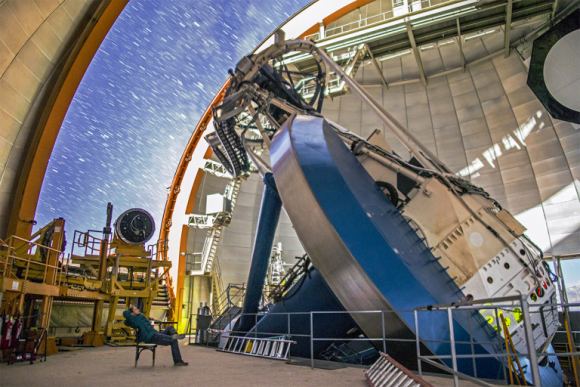

Schneider used the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) on the Hubble to study the system. The system’s inner disk was already well-known, but studying the larger structure has revealed more complexity.

The origin of this vast structure of dusty debris is likely collisions between newly forming planets within the smaller inner ring. Outward pressure from the star HR 4769A then propelled the dust outward into space. The star is 23 times more luminous than our Sun, so it has the necessary energy to send the dust such a great distance.

A press release from NASA describes this vast exo-ring structure as a “donut-shaped inner tube that got hit by a truck.” It extends much further in one direction than the other, and looks squashed on one side. The paper presents a couple possible causes for this asymmetric extension.

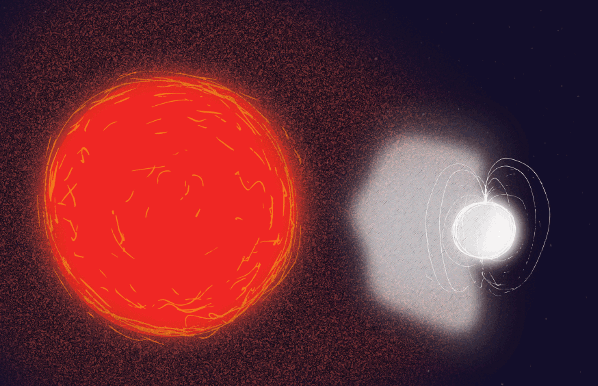

It could be a bow wave caused by the host star travelling through the interstellar medium. Or it could be under the gravitational influence of the star’s binary companion (HR 4796B), a red dwarf star located 54 billion miles from the primary star.

“The dust distribution is a telltale sign of how dynamically interactive the inner system containing the ring is'” – Glenn Schneider, University of Arizona, Tucson.

The asymmetrical nature of the vast exo-structure points to complex interactions between all of the stars and planets in the system. We’re accustomed to seeing the radiation pressure from the host star shape the gas and dust in a circumstellar disk, but this study presents us with a new level of complexity to account for. And studying this system may open a new window into how solar systems form over time.

“We cannot treat exoplanetary debris systems as simply being in isolation. Environmental effects, such as interactions with the interstellar medium and forces due to stellar companions, may have long-term implications for the evolution of such systems. The gross asymmetries of the outer dust field are telling us there are a lot of forces in play (beyond just host-star radiation pressure) that are moving the material around. We’ve seen effects like this in a few other systems, but here’s a case where we see a bunch of things going on at once,” Schneider further explained.

The paper suggests that the location and brightness of smaller rings within the larger dust structure places constraints on the masses and orbits of planets within the system, even when the planets themselves can’t be seen. But that will require more work to determine with any specificity.

This paper represents a refinement and advancement of the Hubble’s imaging capabilities. The paper’s author is hopeful that the same methods using in this study can be used on other similar systems to better understand these larger dust structures, how they form, and what role they play.

As he says in the paper’s conclusion, “With many, if not most, technical challenges now understood and addressed, this capability should be used to its fullest, prior to the end of the HST mission, to establish a legacy of the most robust images of high-priority exoplanetary debris systems as an enabling foundation for future investigations in exoplanetary systems science.”