An astrophotographer in California has captured images of Elon Musk’s Tesla Roadster on its journey around our Sun. In the early morning of February 9th, Rogelio Bernal Andreo captured images of the Roadster as it appeared just above the horizon. To get the images, Andreo made use of an impressive arsenal of technological tools.

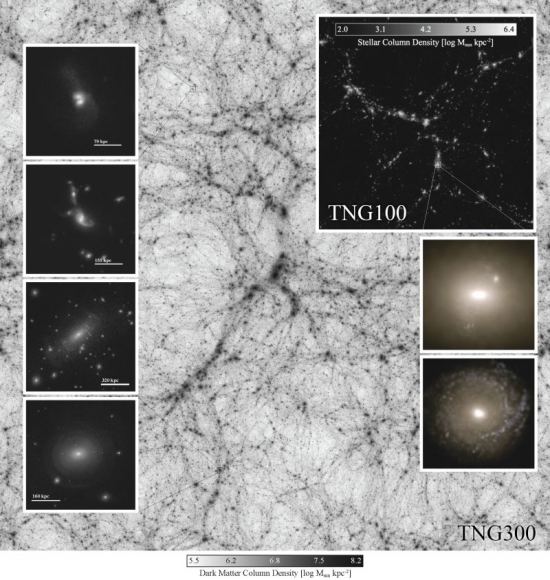

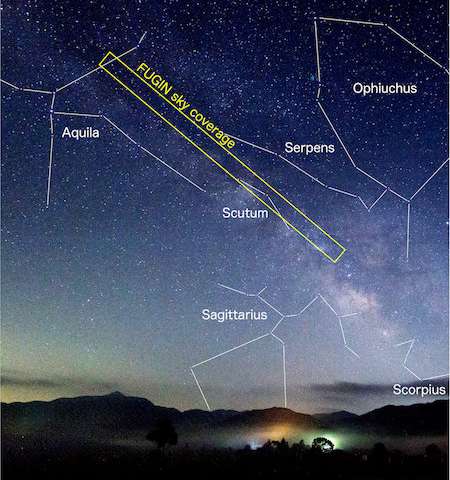

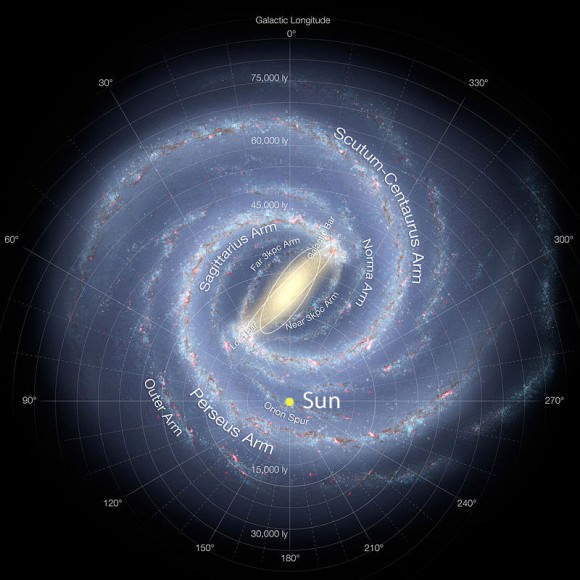

Andreo knew that photographing the Roadster would be a challenge, since it was over a million miles away at the time. But he has the experience and equipment to pull it off. The first task was to determine where the Tesla would be in the sky. Luckily, NASA’s JPL creates lists of coordinates for objects in the sky, called ephemerides. Andreo found the ephemeris for Starman and the Roadster, and it showed that the pair would be in the Hydra constellation, and that they would be only about 20 degrees above the horizon. That’s a challenge, because it means photographing through more atmospheric density.

However, the Roadster and its driver would be bright enough to do it. As Andreo says in his blog, “The ephemeris from the JPL also indicated that the Roadster’s brightness would be at magnitude 17.5, and I knew that’s perfectly achievable.” So he gathered his gear, hopped in his vehicle, and went for it.

Andreo’s destination was the Monte Bello Open Space Preserve, a controlled-access area for which he has a night-time use permit. This area is kind of close to the San Francisco Bay Area, so the sky is a little bright for astrophotography, but since the Roadster has a magnitude of 17.5, he thought it was doable. Plus, it’s a short drive from his home.

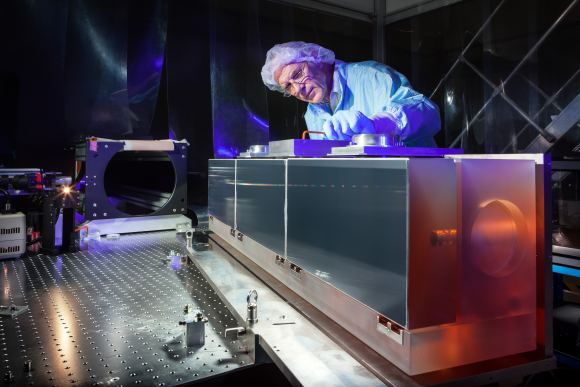

Once he arrived there, he set up his impressive array of gear: dual telescopes and cameras, along with a tracking telescope and computers running specialized software. Andreo explains it best:

“Let me give you a brief description of my gear – also the one I use for most of my deep-sky images. I have a dual telescope system: two identical telescopes and cameras in parallel, shooting simultaneously at the very same area of the sky – same FOV, save a few pixels. The telescopes are Takahashi FSQ106EDX. Their aperture is 106mm (about 4″) and they give you a native 530mm focal length at f/5. The cameras are SBIG STL11k monochrome CCD cameras, one of the most legendary full-frame CCD cameras for astronomy (not the best one today, mind you, but still pretty decent). All this gear sits on a Takahashi EM-400 mount, the beast that will move it at hair-thin precision during the long exposures. I brought the temperature of the CCD sensors to -20C degrees (-4F) using the CCD’s internal cooling system.”

CCD’s with internal cooling systems. Very impressive!

Andreo uses a specialized focusing system to get his images. He uses focusers from Robofocus and precision focusing software called FocusMax. He also uses a third, smaller telescope called an autoguider. It focuses on a single star in the Field of View and follows it religiously. When that star moves, the whole rig moves. As Andreo says on his blog, “Autoguiding provides a much better mount movement than tracking, which is leaving up to the mount to blindly “follow” the sky. By actually “following” a star, we can make sure there’ll be no trails whether our exposures are 2 or 30 minutes long.”

Once he was all set up, there was time pressure. The Roadster would only be above the horizon for a short time and the Moon was coming up and threatening to wash out the sky. Andreo got going, but his first shots showed nothing.

Andreo felt that once he got home and could process the images properly, the Tesla Roadster and its driver would be somewhere in his images. He kept taking pictures until about 5 AM. Cold and tired, he finally packed up his gear and went home.

“…no matter what I did, I could not find the Roadster.” Astrophotographer Rogelio Bernal Andreo

After some sleep, he began working with his images. “After a few hours of sleep, I started playing with the data and no matter what I did, I could not find the Roadster. I kept checking the coordinates, nothing made sense. So I decided to try again. The only difference would be that this time the Moon would rise around 3:30am, so I could try star imaging at 2:30am and get one hour of Moon-free skies, maybe that would help.”

So Andreo set out to capture the Roadster again. The next night, at the same location, he set up his gear again. But this time, some clouds rolled in, and Andreo got discouraged. He stayed to wait for the sky to improve, but it didn’t. By about 4 AM he packed up and headed home.

After a nap, he went over his photos, but still couldn’t find the Roadster. It was a puzzle, because he knew the Roadster’s coordinates. Andreo is no rookie, his photos have been published many times in Astronomy Magazine, Sky and Telescope, National Geographic, and other places. His work has also been chosen as NASA’s APOD (Astronomy Picture of the Day) more than 50 times. So when he can’t find something in his images that should be there, it’s puzzling.

Then he had an A-HA! moment:

“Then it hit me!! When I created the ephemeris from the JPL’s website, I did not enter my coordinates!! I went with the default, whatever that might be! Since the Roadster is still fairly close to us, parallax is significant, meaning, different locations on Earth will see Starman at slightly different coordinates. I quickly recalculate, get the new coordinates, go to my images and thanks to the wide field captured by my telescopes… boom!! There it was!! Impossible to miss!! It had been right there all along, I just never noticed!”

Andreo is clearly a dedicated astrophotographer, and this is a neat victory for him. He deserves a tip of the hat from space fans. Why not check out his website—his gallery is amazing!—and share a comment with him.

Rogelio Bernal Andreo’s website: DeepSkyColors.com

His gallery: http://www.deepskycolors.com/rba_collections.html

Also, check out his Flickr page: https://www.flickr.com/photos/deepskycolors/

Andreo explained how he got the Roadster images in this post on his blog: Capturing Starman from 1 Million Miles