We humans have an insatiable hunger to understand the Universe. As Carl Sagan said, “Understanding is Ecstasy.” But to understand the Universe, we need better and better ways to observe it. And that means one thing: big, huge, enormous telescopes.

In this series we’ll look at the world’s upcoming Super Telescopes:

- The Giant Magellan Telescope

- The Overwhelmingly Large Telescope

- The 30 Meter Telescope

- The European Extremely Large Telescope

- The Large Synoptic Survey Telescope

- The James Webb Space Telescope

- The Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope

- The Large UV Optical Infrared Surveyor (LUVOIR)

The Large UV Optical Infrared Surveyor Telescope (LUVOIR)

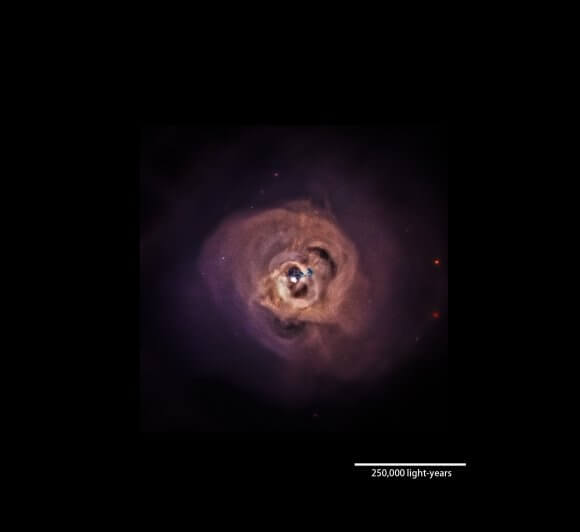

There’s a whole generation of people who grew up with images from the Hubble Space Telescope. Not just in magazines, but on the internet, and on YouTube. But within another generation or two, the Hubble itself will seem quaint, and watershed events of our times, like the Moon Landing, will be just black and white relics of an impossibly distant time. The next generations will be fed a steady diet of images and discoveries stemming from the Super Telescopes. And the LUVOIR will be front and centre among those ‘scopes.

If you haven’t yet heard of LUVOIR, it’s understandable; LUVOIR is in the early stages of being defined and designed. But LUVOIR represents the next generation of space telescopes, and its power will dwarf that of its predecessor, the Hubble.

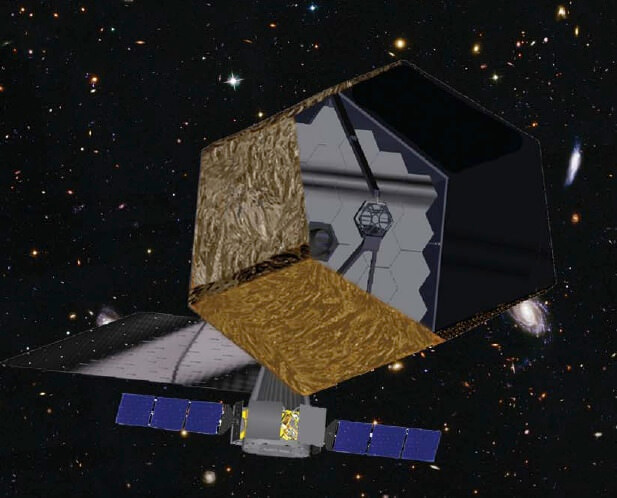

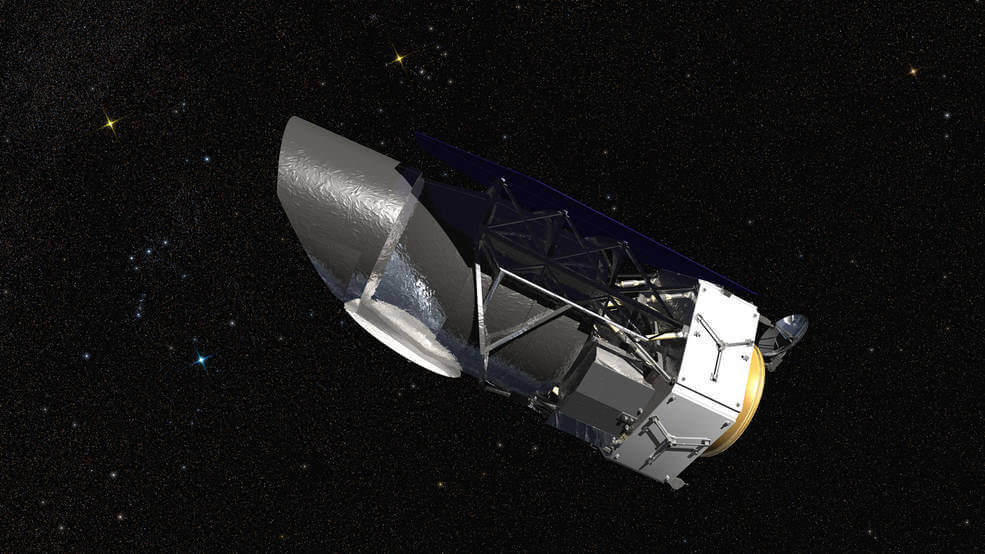

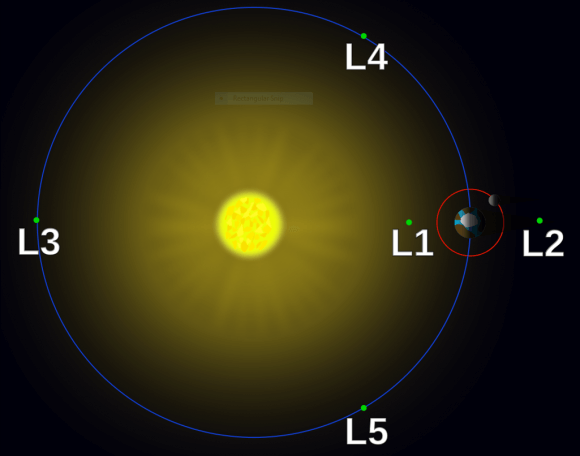

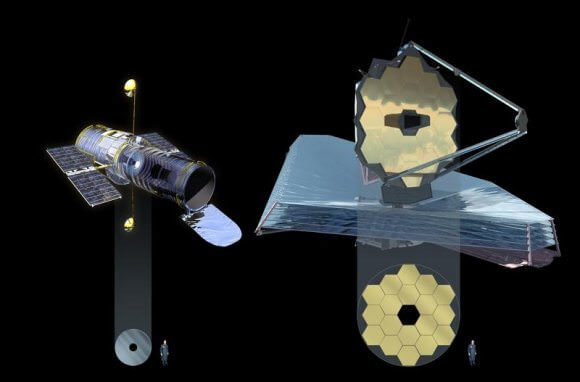

LUVOIR (its temporary name) will be a space telescope, and it will do its work at the LaGrange 2 point, the same place that JWST will be. L2 is a natural location for space telescopes. At the heart of LUVOIR will be a 15m segmented primary mirror, much larger than the Hubble’s mirror, which is a mere 2.4m in diameter. In fact, LUVOIR will be so large that the Hubble could drive right through the hole in the center of it.

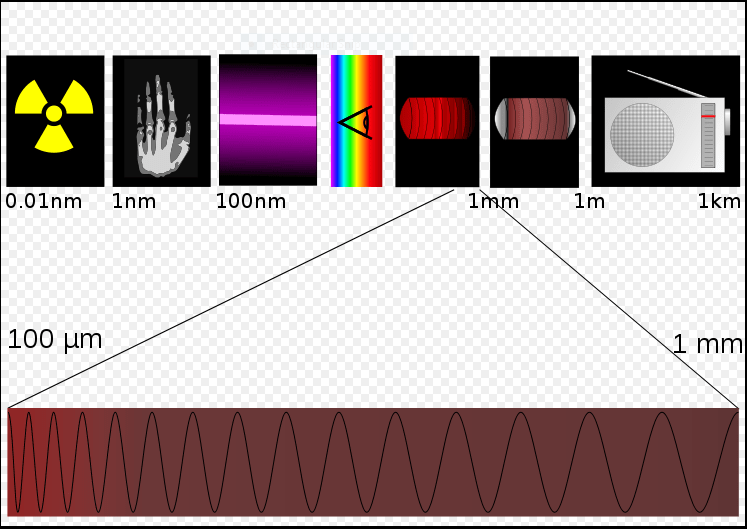

While the James Webb Space Telescope will be in operation much sooner than LUVOIR, and will also do amazing work, it will observe primarily in the infrared. LUVOIR, as its name makes clear, will have a wider range of observation more like Hubble’s. It will see in the Ultra-Violet spectrum, the Optical spectrum, and the Infrared spectrum.

Recently, Brad Peterson spoke with Fraser Cain on a weekly Space Hangout, where he outlined the plans for the LUVOIR. Brad is a recently retired Professor of Astronomy at the Ohio State University, where served as chair of the Astronomy Department for 9 years. He is currently the chair of the Science Committee at NASA’s Advisory Council. Peterson is also a Distinguished Visiting Astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute, and the chair of the astronomy section of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

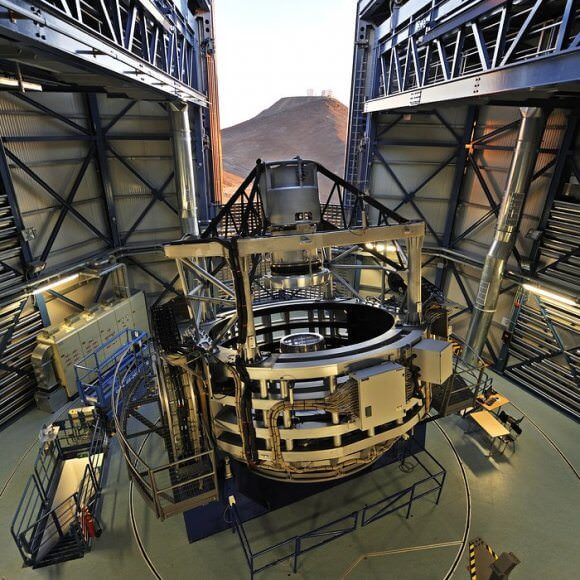

Different designs for LUVOIR have been discussed, but as Peterson points out in the interview above, the plan seems to have settled on a 15m segmented mirror. A 15m mirror is larger than any optical light telescope we have on Earth, though the Thirty Meter Telescope and others will soon be larger.

“Segmented telescopes are the technology of today when it comes to ground-based telescopes. The JWST has taken that technology into space, and the LUVOIR will take segmented design one step further,” Peterson said. But the segmented design of LUVOIR differs from the JWST in several ways.

“…the LUVOIR will take segmented design one step further.” – Brad Peterson

JWST’s mirrors are made of beryllium and coated with gold. LUVOIR doesn’t require the same exotic design. But it has other requirements that will push the envelope of segmented telescope design. LUVOIR will have a huge array of CCD sensors that will require an enormous amount of electrical power to operate.

LUVOIR will not be cryogenically cooled like the JWST is, because it’s not primarily an Infrared observatory. LUVOIR will also be designed to be serviceable. In fact, the US Congress now requires all space telescopes to be serviceable.

“Congress has mandated that all future large space telescopes must be serviceable if practicable.” – Brad Peterson

LUVOIR is designed to have a long life. It’s multiple instruments will be replaceable, and the hope is that it will last in space for 50 years. Whether it will be serviced by robots, or by astronauts, has not been determined. It may even be designed so that it could be brought back from L2 for servicing.

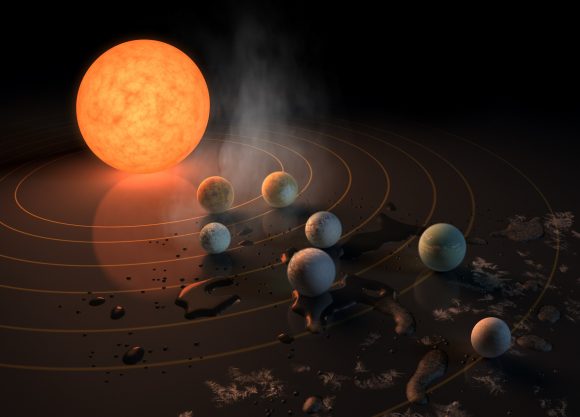

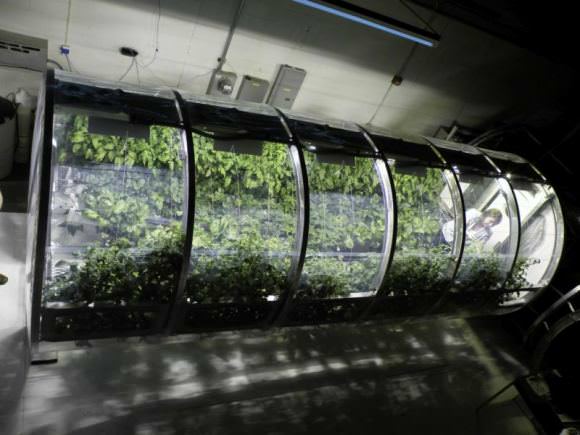

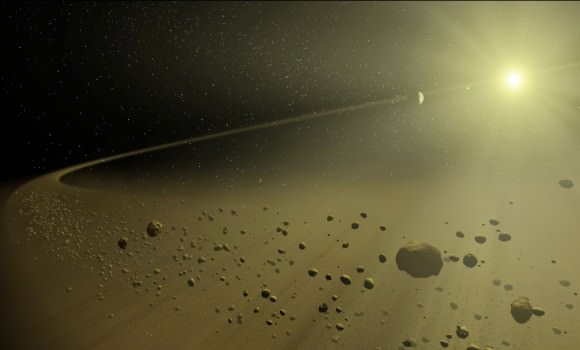

LUVOIR will contribute to the search for life on other worlds. A key requirement for LUVOIR is that it do spectroscopy on the atmospheres of distant planets. If you can do spectroscopy, then you can determine habitability, and, potentially, even if a planet is inhabited. This is the first main technological challenge for LUVOIR. This spectroscopy requires a powerful coronagraph to suppress the light of the stars that exoplanets orbit. LUVOIR’s coronagraph will excel at this, with a ratio of starlight suppression of 10 billion to 1. With this capability, LUVOIR should be able to do spectroscopy on the atmospheres of small, terrestrial exoplanets, rather than just larger gas giants.

“This telescope is going to be remarkable. The key science that it’s going to do be able to do is spectroscopy of planets in the habitable zone around nearby stars.” – Brad Peterson

This video from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center talks about the search for life, and how telescopes like LUVOIR will contribute to the search. At the 15:00 mark, Dr. Aki Roberge talks about how spectroscopy is key to finding signs of life on exoplanets, and how LUVOIR will take that search one step further.

Using spectroscopy to search for signs of life on exoplanets is just one of LUVOIR’s science goals.

LUVOIR is tasked with other challenges as well, including:

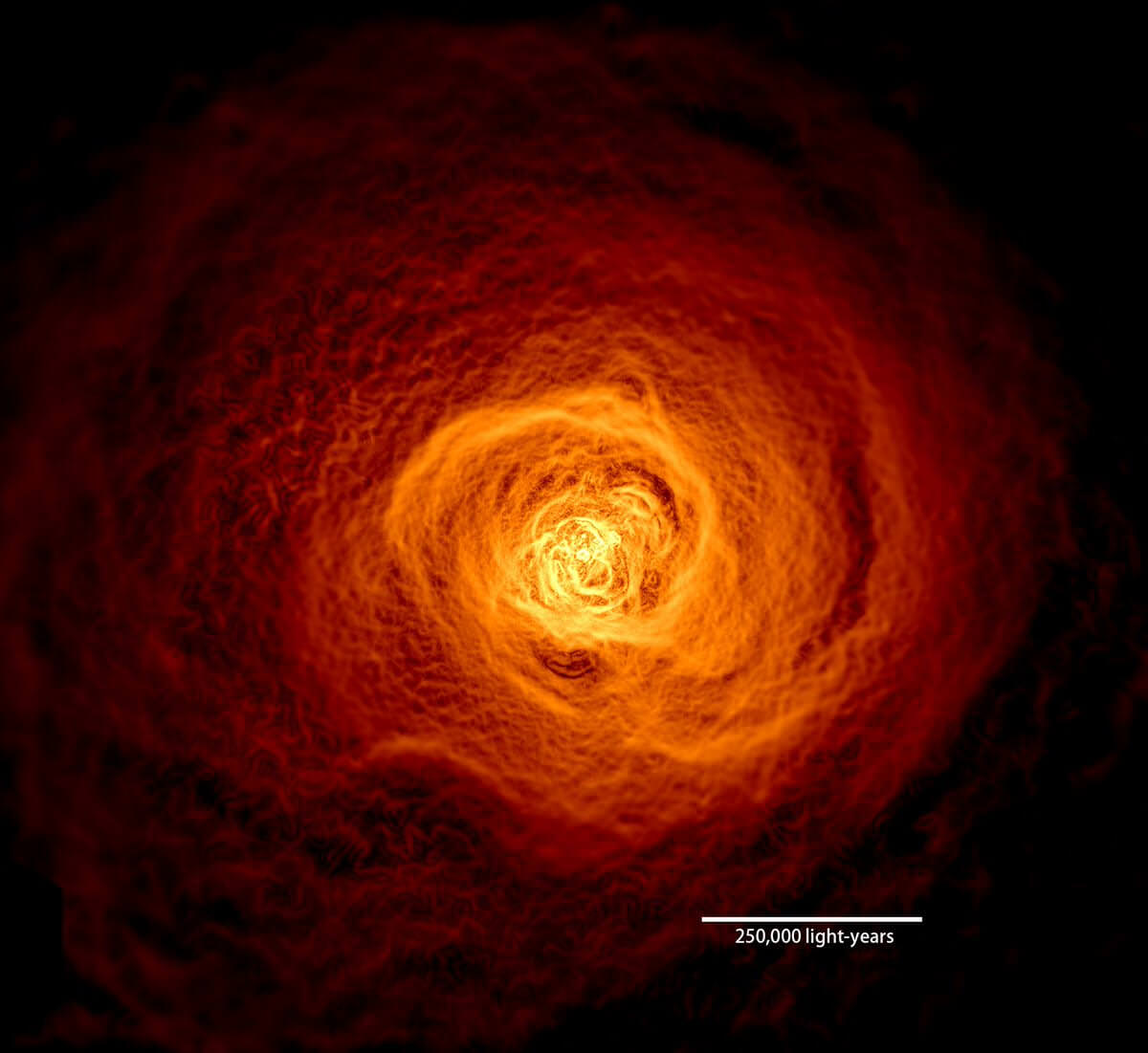

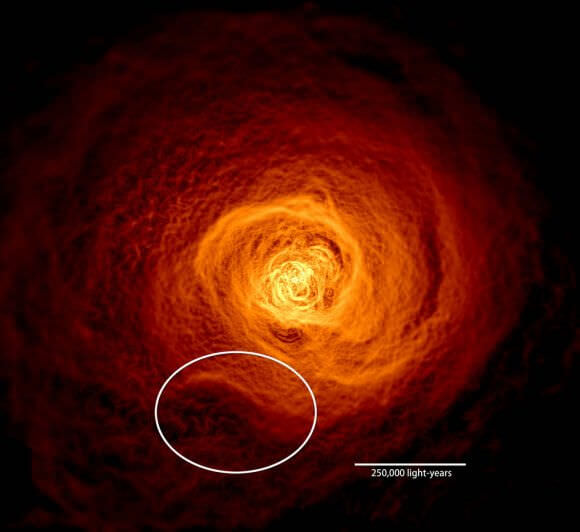

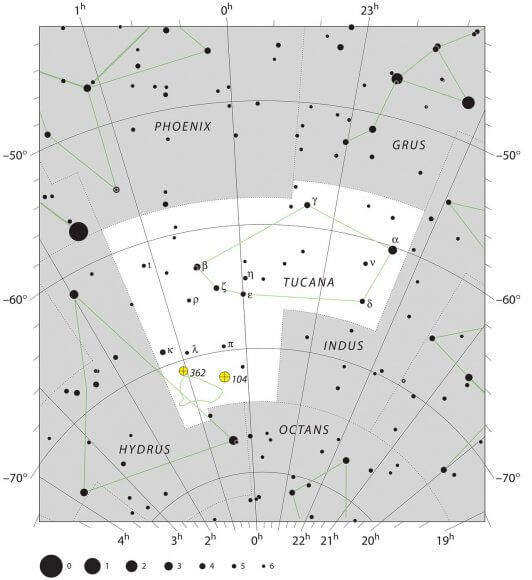

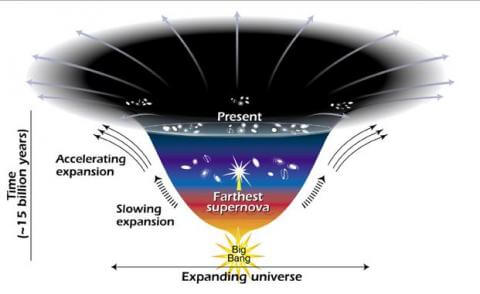

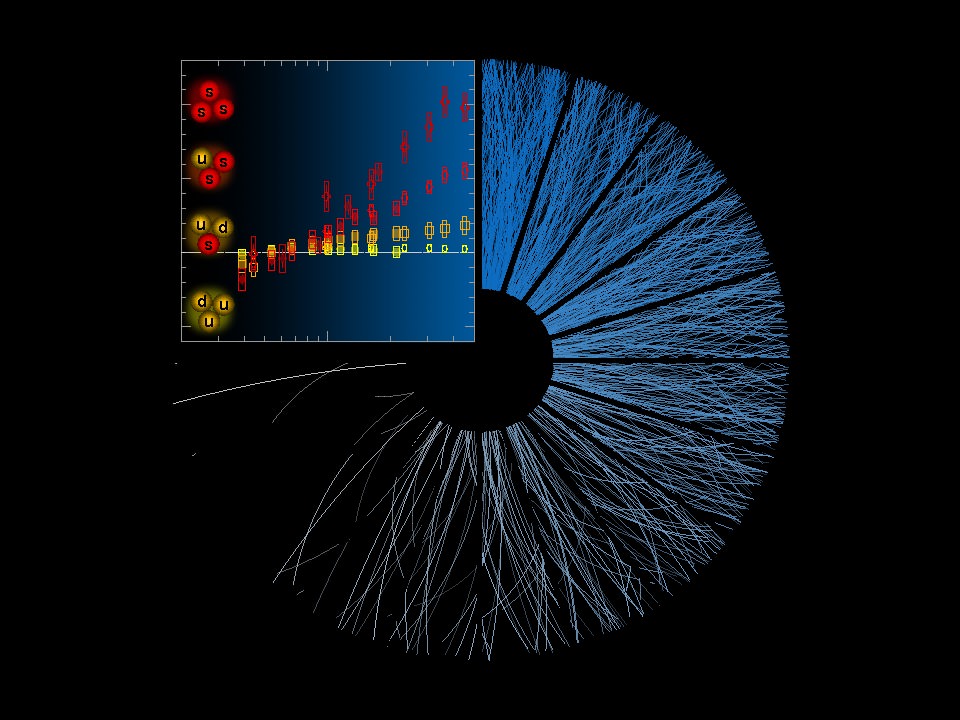

- Mapping the distribution of dark matter in the Universe.

- Isolating the source of gravitational waves.

- Imaging circumstellar disks to see how planets form.

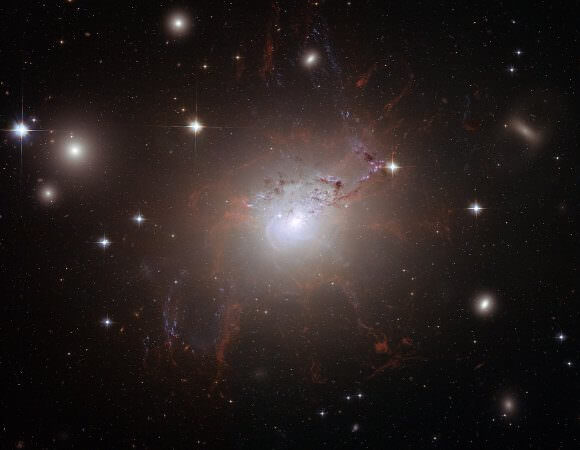

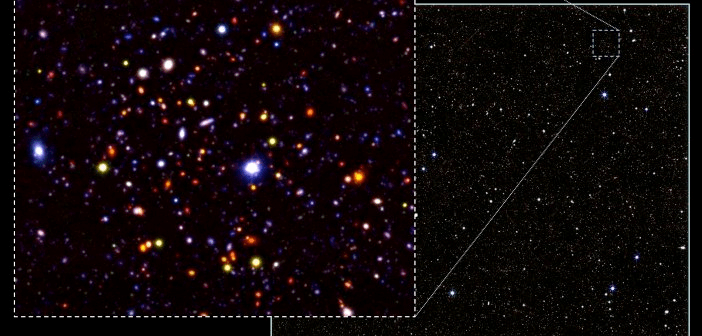

- Identifying the first starlight in the Universe, studying early galaxies and finding the first black holes.

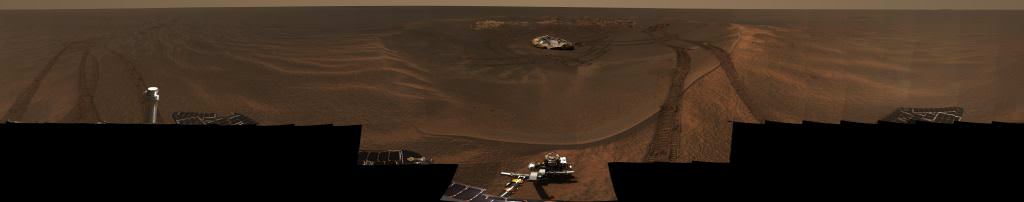

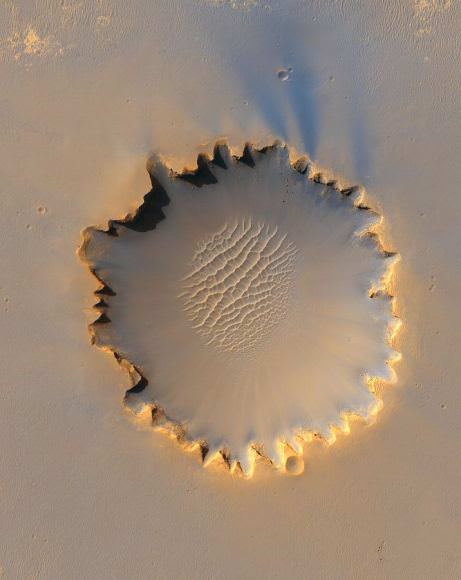

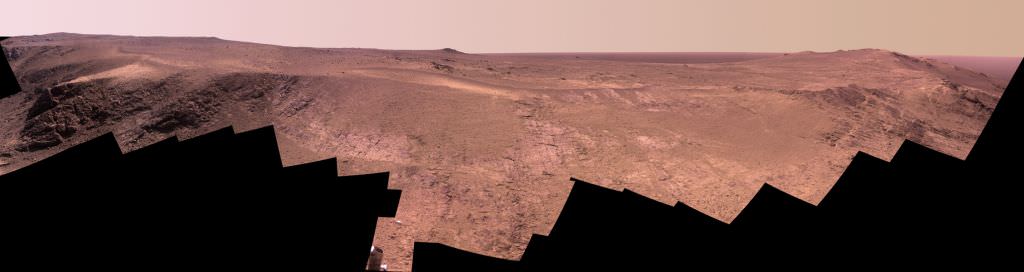

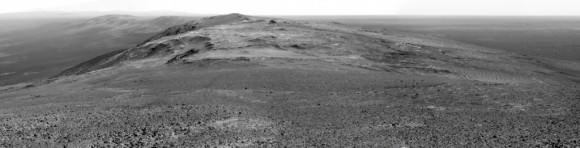

- Studying surface features of worlds in our Solar System.

To tackle all these challenges, LUVOIR will have to clear other technological hurdles. One of them is the requirement for long exposure times. This puts enormous constraints on the stability of the scope, since its mirror is so large. A system of active supports for the mirror segments will help with stability. This is a trait it shares with other terrestrial Super Telescopes like the Thirty Meter Telescope and the European Extremely Large Telescope. Each of those had hundreds of segments which have to be controlled precisely with computers.

Credit: NASA

LUVOIR’s construction, and how it will be placed in orbit are also significant considerations.

According to Peterson, LUVOIR could be launched on either of the heavy lift rockets being developed. The Falcon Heavy is being considered, as is the Space Launch System. The SLS Block 1B could do it, depending on the final size of LUVOIR.

“I’s going to require a heavy lift vehicle.” – Brad Peterson

Or, LUVOIR may never be launched into space. It could be assembled in space with pre-built components that are launched one at a time, just like the International Space Station. There are several advantages to that.

With assembly in space, the telescope doesn’t have to be built to withstand the tremendous force it takes to launch something into orbit. It also allows for testing when completed, before being sent to L2. Once the ‘scope was assembled and tested, a small ion propulsion engine could be used to power it to L2.

It’s possible that the infrastructure to construct LUVOIR in space will exist in a decade or two. NASA’s Deep Space Gateway in cis-lunar space is planned for the mid-20s. It would act as a staging point for deep-space missions, and for missions to the lunar surface.

LUVOIR is still in the early stages. The people behind it are designing it to meet as many of the science goals as they can, all within the technological constraints of our time. Planning has to start somewhere, and the plans presented by Brad Peterson represent the current thinking behind LUVOIR. But there’s still a lot of work to do.

“Typical time scale from selection to launch of a flagship mission is something like 20 years.” – Brad Peterson

As Peterson explains, LUVOIR will have to be chosen as NASA’s highest priority during the 2020 Decadal Survey. Once that occurs, then a couple more years are required to really flesh out the design of the mission. According to Peterson, “Typical time scale from selection to launch of a flagship mission is something like 20 years.” That gets us to a potential launch in the mid-2030s.

Along the way, LUVOIR will be given a more suitable name. James Webb, Hubble, Kepler and others have all had important missions named after them. Perhaps its Carl Sagan’s turn.

“The Carl Sagan Space Telescope” has a nice ring to it, doesn’t it?