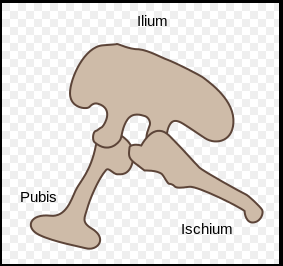

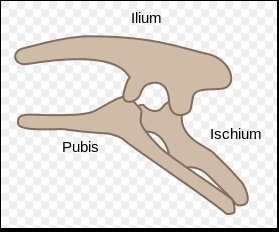

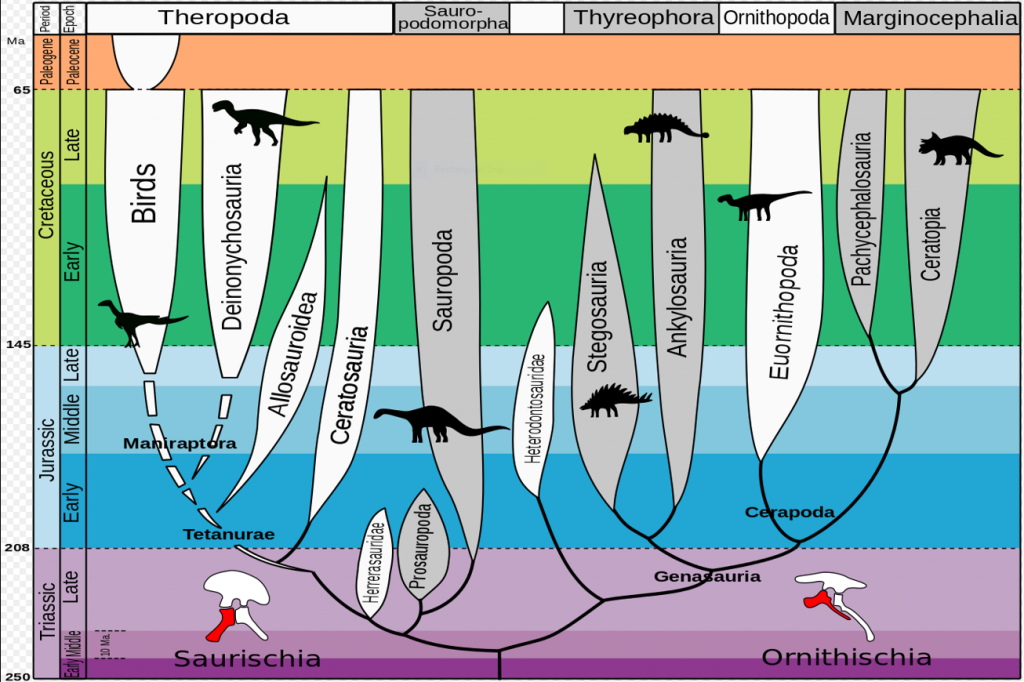

To kids, there are only two kinds of dinosaurs: meat-eaters and plant-eaters. But to paleontologists, those are just diet distinctions. Paleontologists divide dinos into two different groups based largely on pelvic structure: reptile-hipped saurischians, and bird-hipped ornithischians.

Those two categories are called ‘clades’, and they’re fundamental to the study of dinosaurs. But a new study is casting doubt on those two groups, as well as moving the infamous Tyrannosaurus Rex to a new spot on the dinosaur family tree.

The study, by Matthew G. Baron, David B. Norman & Paul M. Barrett, was published in the journal Nature. If the findings in this study are accepted by paleontologists, then it will upset our understanding of the family tree that was first established in Victorian times.

The T. Rex is the most famous member of the reptile-hipped saurischians. Many other carnivorous theropods are saurischians too, like Giganotosaurus and Spinosaurus. Other famous dinosaurs, like Stegosaurus, are bird-hipped ornithischians. The distinction between the saurischians and the ornithischians has been workable for a long time. But there were always problems with the two clades of dinosaurs.

Some of the earliest ornithischian dinosaurs in the Triassic period had some theropod qualities: they were bipedal and probably meat-eaters. This clouded the separation between ornithischians and saurischians. There are also the herrerasaurids, small dinosaurs not larger than 4 meters long. They were some of the earliest dinosaurs, carnivores that look like both sauropods and theropods, and even though they appear early in the fossil record, they are not considered ancestors to any other group of dinosaurs. They show a mixture of both primitive and derived traits.

Huge plant-eating sauropods like the Brontosaurus and the Diplodocus are included in the reptile-hipped saurischians with the meat-eating theropods, even though there are some key skeletal differences between the two groups.

Another problem centers around birds. Believe it or not, birds have theropods as ancestors, even though theropods are in the reptile-hipped clade, rather than the bird-hipped clade.

Are You Confused Yet?

If this all seems kind of confusing, let’s back up for a minute.

When we think of dinosaurs, we tend to think of full-scale rebuilt skeletons of the type on display in museums around the world. But for paleontologists, the reality is much different. Many dinosaur species are known only by a few bones or teeth. These samples are studied in great detail. Any groove in a bone or slightly different shape in a tooth is analyzed, and out of this a dinosaur family tree is constructed.

It’s hard work, and our fossil record is spotty at best. Some new dinosaur taxa are proposed based only on the discovery of isolated teeth in the fossil record. With all of this in mind, you can see that the dinosaur family tree is an ongoing work in progress.

The authors of the study say that many ornithischian dinosaurs were overlooked in the past, because paleontologists didn’t really know what to do with them. Many of the ornithischians had weird traits like extra chin bones and molar-like teeth in their cheeks. These ornithischian dinos were thought of as oddities, early offshoots from other species.

New Clades

The authors studied 457 traits in 74 taxa, looking at details like the shapes of tiny eye-socket bones and grooves on femurs. They found that Theropods, even though they have reptile-like hips, don’t belong in the saurischian clade. They’re suggesting that Theropods are a sister clade to the ornithischians. The revised grouping of Ornithischia and Theropoda has been named the Ornithoscelida. The authors are also proposing that the herrerasaurids did not branch off as early as previously thought, and should form a sister clade with the sauropods.

But this study does even more. It’s been long understood by paleontologists that dinosaurs appeared in the southern hemisphere first. That’s where the herrerasaurids were found, dating back to 240 million years ago. The authors remind us that there are very few Herrerasaurus skeletons and bones, and there are uncertainties in the age of the Triassic fossil beds where herrerasaurids are found. A nearly complete skeleton was found in Argentina, and less complete ones have been found in North America.

But this shuffling of the family tree moves the herrerasaurids further away from the base of the tree. Remember, the herrerasaurids look like both sauropods and theropods, and they show both derived and primitive traits. If it’s accepted that the herrerasaurids did not appear as early as thought, that might mean that dinos did not appear first in the southern hemisphere. The authors say that some enigmatic fossils found in the northern hemisphere should be re-examined in case they are earlier than the ones found in the south.

Enter the Saltopus

A fossil of a cat-like creature found in Scotland, called the Saltopus, is a part of the shake-up of the dinosaur family tree. It was considered a pre-cursor to dinosaurs, rather than a true dinosaur. As part of their analysis, the Saltopus has been re-positioned in the earliest part of the dinosaur lineage, as the first true dinosaur. This supports the idea that dinosaurs appeared first in the northern hemisphere rather than the south.

If this new family tree for dinosaurs is accepted, it will change our understanding of the way dinosaurs evolved. We’ve relied on similarity in hip shape to ascertain ancestry, but that may be a little simplistic.

Our understanding of dinosaurs changes frequently. Remember when dinosaurs were slow, dim-witted creatures with tiny brains and huge bodies? Now we think of dinosaurs as feathered and fast, using cunning and perhaps teamwork to hunt in packs. Remember when the prevailing wisdom was that some dinosaurs got so large and spiny that they were doomed to extinction? That was proven false as well.

If it does stick, this new family tree will be a huge change in paleontology, a field where knowledge is overturned on a regular basis, sometimes by little more than a few teeth.