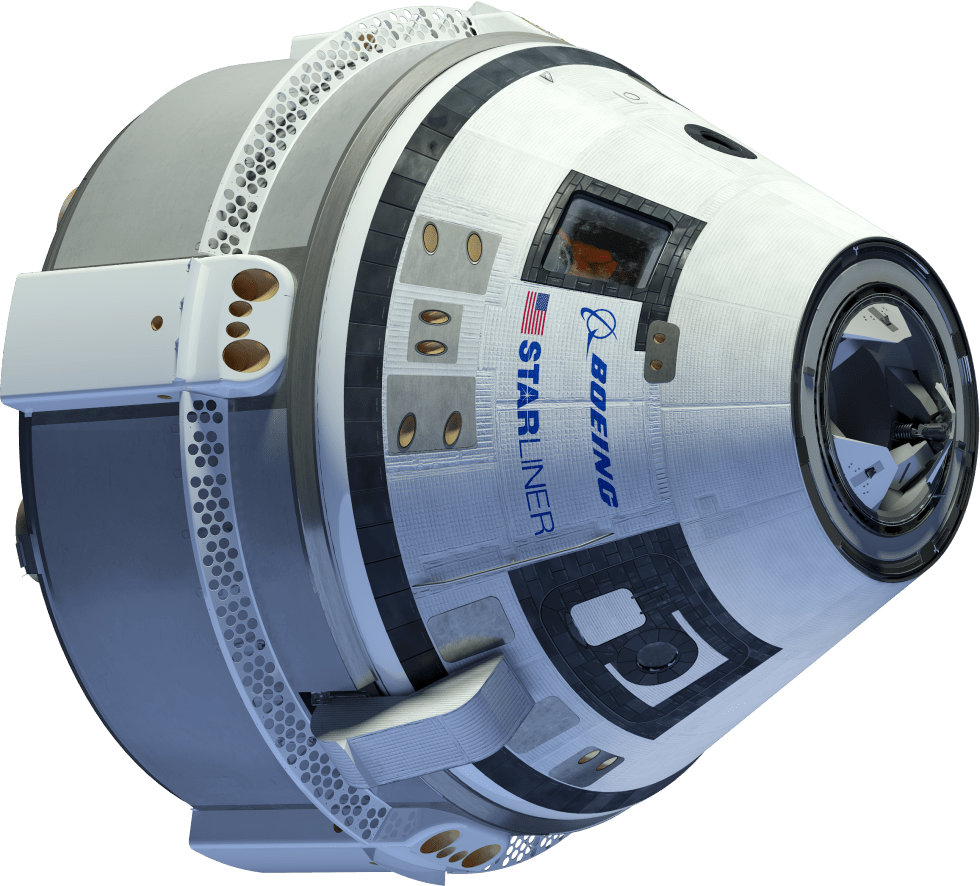

Boeing thinks it can have its Starliner spacecraft ready to fly crewed missions by February, 2018. This is 4 months later than the previous date of October 2017. It isn’t yet clear what this will mean in Boeing’s race against SpaceX to relieve NASA’s dependence on Russian transportation to the ISS.

Currently, astronauts travel to the ISS aboard the Russian workhorse Soyuz capsule. Ever since the end of the Space Shuttle program, NASA has relied on Russia to transport astronauts to the station. Both Boeing and SpaceX have received funds to develop a crewed capsule, and both companies are working at a feverish pace to be the first to do so.

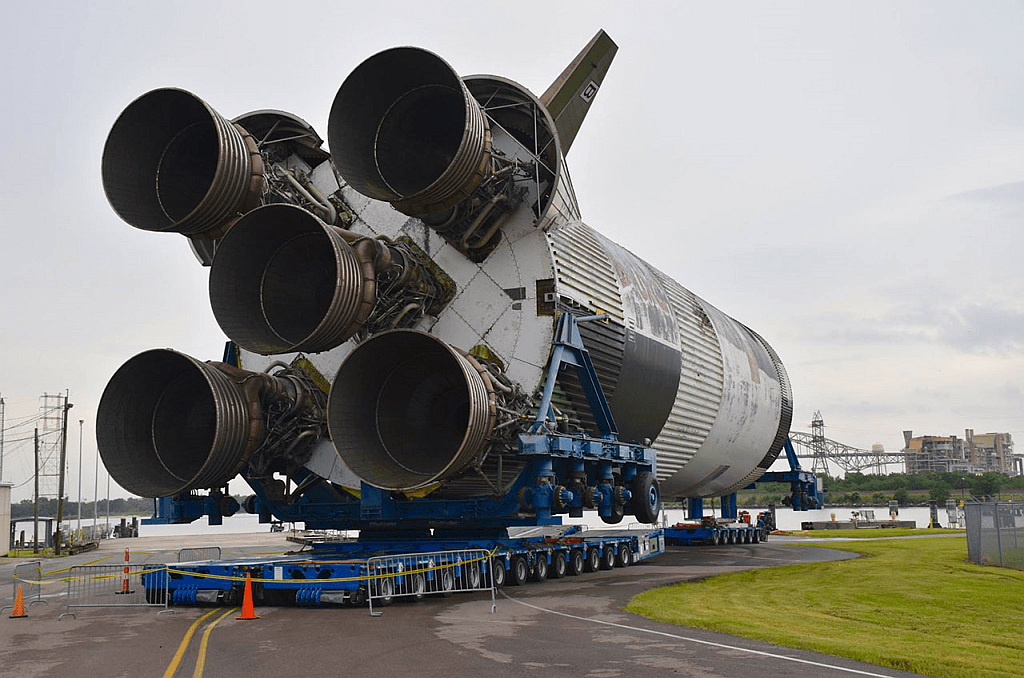

Boeing has a long history of involvement with NASA. It’s the prime contractor for ISS operations, and is also the prime contractor for NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS), which will be the most powerful rocket ever built and will power NASA’s exploration of deep space. So Boeing is no stranger to complex development cycles and the types of delays that can crop up.

In a recent interview, Boeing’s Chris Ferguson acknowledged that everything has to go well for the Starliner to meet its schedule. But things don’t always go well in such a complex engineering program, and that’s just the way things are.

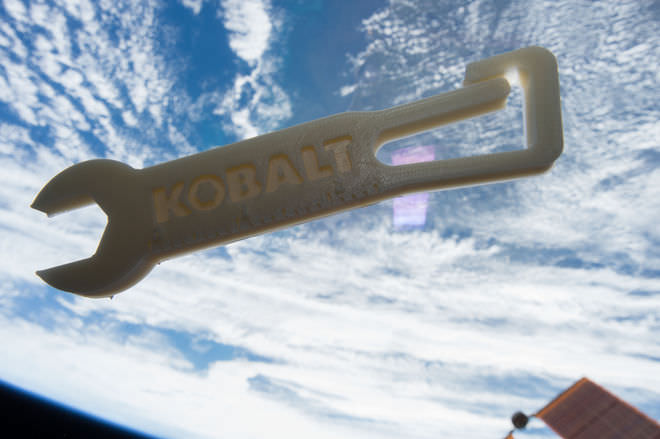

The Starliner, and every other spacecraft, has to undergo extensive testing of each component before any flight can be attempted. Various suppliers are responsible for over 200 pieces of equipment, just in avionics alone, and each one of those pieces has to assembled, integrated, and tested. Not just by Boeing, but by NASA as well. This takes an enormous amount of time, and requires great rigor to carry out. In some cases, a problem with one piece of equipment can delay testing of other pieces. It’s the nature of complex systems.

Another challenge that Boeing engineers face is limiting the mass of the spacecraft. Recent wind-tunnel testing of a Starliner model produced aero-acoustic issues when mated to a model of the Atlas 5, the rocket built by United Launch Alliance (ULA) which will carry the Starliner into space. Now Boeing is modifying the exterior lines of the vehicle to get the airflow just right.

The spacecraft also has to be tested for emergencies. Though the Starliner is designed to land on solid ground, it’s also being tested for emergency landings on water.

NASA blames the delays in the development of the Starliner, and the SpaceX Dragon, on funding cuts from Congress. Administrator Charles Bolden has criticized Congress for consistent under-funding since the retirement of the Space Shuttle fleet in 2011. According to NASA, this has caused a 2 year delay in development of the Dragon and the Starliner. This delay, in turn, has meant that NASA has had to keep paying Russia for trips to the ISS. And like everything else, that cost keeps rising.

But it looks like the end, or maybe the beginning, is in sight for the Starliner. Boeing has paid deposits to ULA for four flights with the Atlas 5. A 2017 un-crewed test flight, a 2018 crewed test flight, and two crewed flights to the ISS.

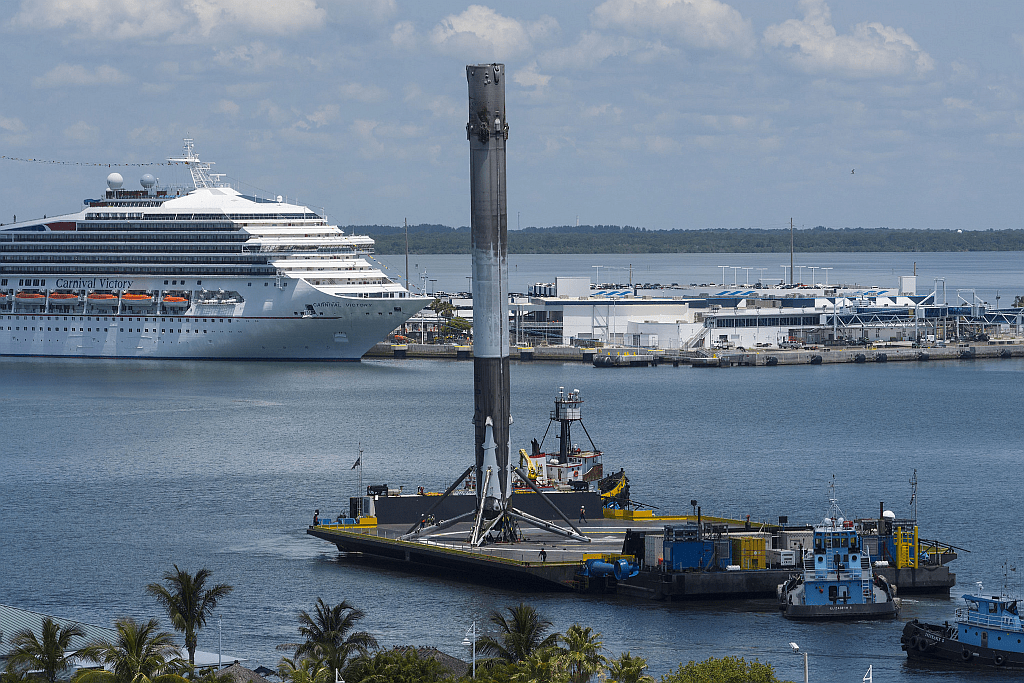

Beyond that, the future looks a little hard to predict for Boeing and the Starliner. With both SpaceX and Blue Origin developing re-usable rockets, the future viability of the Atlas 5 might be in jeopardy. Compounding the uncertainty is NASA’s stated plan to stop funding the ISS by 2024 or 2028.

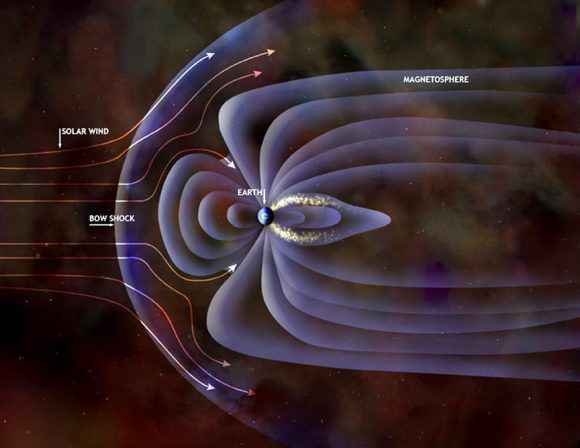

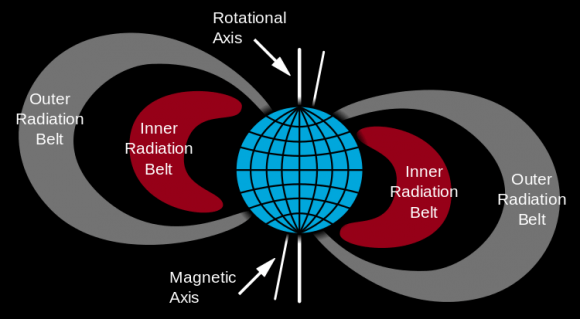

By that time, NASA should be focused on establishing a presence in cislunar space, which would require different spacecraft.

But you can’t wait forever to develop spacecraft. The only way to stay in the game is for Boeing to develop the spacecraft that are required right now, and let the knowledge and experience from that feed the development of the next spacecraft, whether for cislunar space or beyond.

In the big scheme of things, a four month delay for the first flight of the Starliner is not that big of a deal. If the Starliner is successful, and there’s no reason to think it won’t be, considering Boeing’s track record, the four month delay in the initial flight won’t even be remembered.

Whether its SpaceX or Boeing who get America back into space first, that moment will be celebrated, and all the delays and funding cuts will be left in the dust-bin of history.