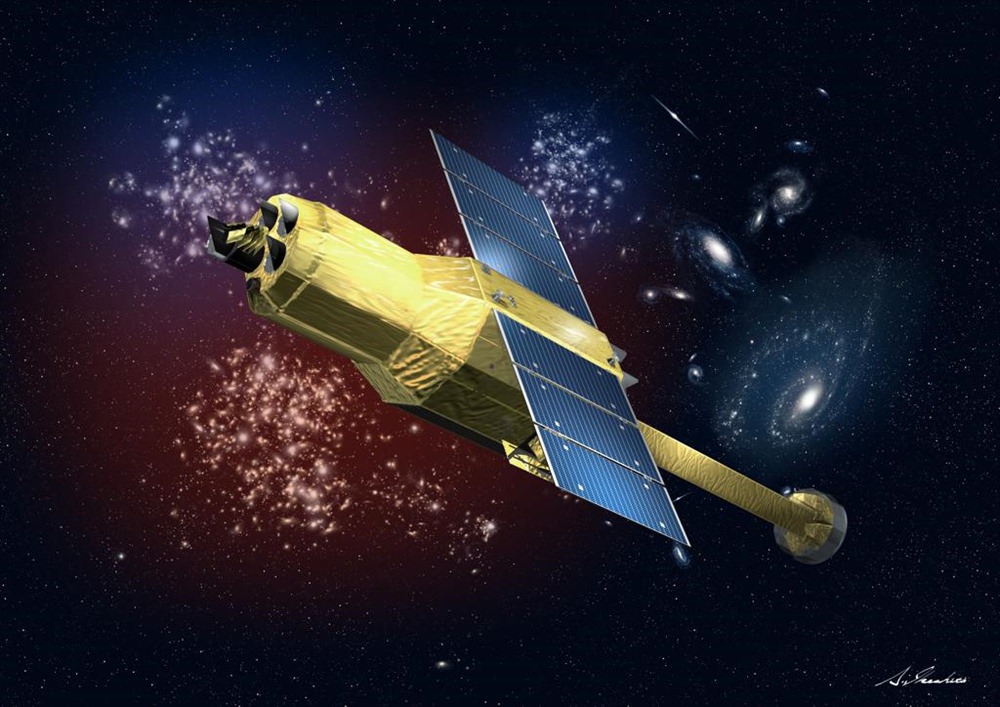

The Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) has lost contact with its X-ray Astronomy Satellite Hitomi (ASTRO-H.) Hitomi was launched on February 17th, for a 3-year mission to study black holes. But now that mission appears to be in jeopardy.

Hitomi is a collaboration between JAXA and NASA. Its mission was to investigate how galaxy clusters were formed and influenced by dark matter and dark energy, and to understand how super-massive black holes form and evolve at the center of galaxies. Hitomi was also to “unearth the physical laws governing extreme conditions in neutron stars and black holes,” according to JAXA.

Japan has managed two very short communications with Hitomi, but they were very brief, and JAXA has not been able to determine the nature of the problem. Now, JSpOC, the US Joint Space Operations Center, say they have detected debris in the vicinity of Hitomi, and in a press release this morning (March 29th), JAXA says “it is estimated that Hitomi separated to five pieces at about 10:42 a.m.”

Hitomi was going to be an important contribution to the fleet of space telescopes used by astrophysicists and cosmologists. It has a cutting edge instrument called the X-ray micro-calorimeter, which would have observed X-rays from space with the greatest sensitivity of any instrument so far. If all that is lost, it will be quite a blow.

There’s no definitive word yet on what exactly has happened to Hitomi. Japan is using ground stations in different parts of the world to try to communicate with their observatory. It’s important to note that there is no agreement that the craft has broken apart. The press releases are translations from Japanese to English, so the exact meaning of “separated to five pieces” is unclear.

It’s possible that there was a small explosion of some sort, and that some debris from that explosion is in the vicinity of Hitomi. It’s also possible that JAXA will re-establish communications with the craft as time goes on.

Other observatories have suffered serious problems, and have eventually been brought back under control and completed their missions. The ESA/NASA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) suffered serious problems at the beginning of its mission in 1995, entering emergency mode 3 times before all contact was lost. Eventually, SOHO was brought under control, and what was supposed to be a 2-year mission has lasted 20.

Universe Today will be following this story to see if Hitomi can be made operational. For readers wanting to know more about Hitomi’s mission, read JAXA’s excellent Hitomi press kit.