[/caption]

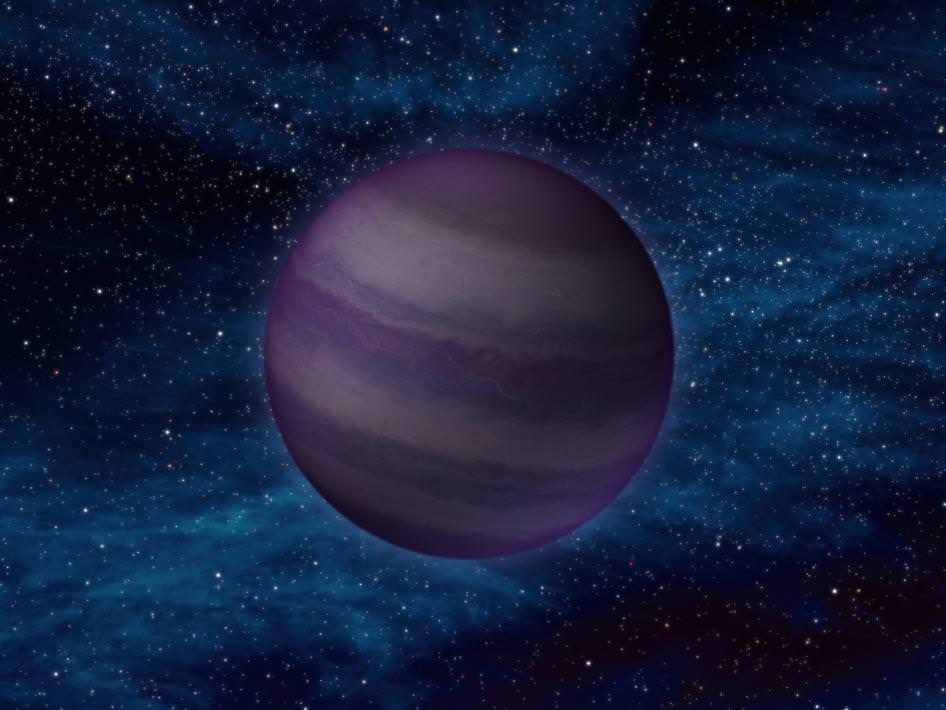

Sometimes called failed stars, brown dwarfs straddle the line between star and planet. Too massive to be “just” a planet, but lacking enough material to start fusion and become a full-fledged star, brown dwarfs are sort of the middle child of cosmic objects. Only first detected in the 1990s, their origins have been a mystery for astronomers. But a researchers from Canada and Austria now think they have an answer for the question: where do brown dwarfs come from?

If there’s enough mass in a cloud of cosmic material to start falling in upon itself, gradually spinning and collapsing under its own gravity to compress and form a star, why are there brown dwarfs? They’re not merely oversized planets — they aren’t in orbit around a star. They’re not stars that “cooled off” — those are white dwarfs (and are something else entirely.) The material that makes up a brown dwarf probably shouldn’t have even had enough mass and angular momentum to start the whole process off to begin with, yet they’re out there… and, as astronomers are finding out now that they know how to look for them, there’s quite a lot.

So how did they form?

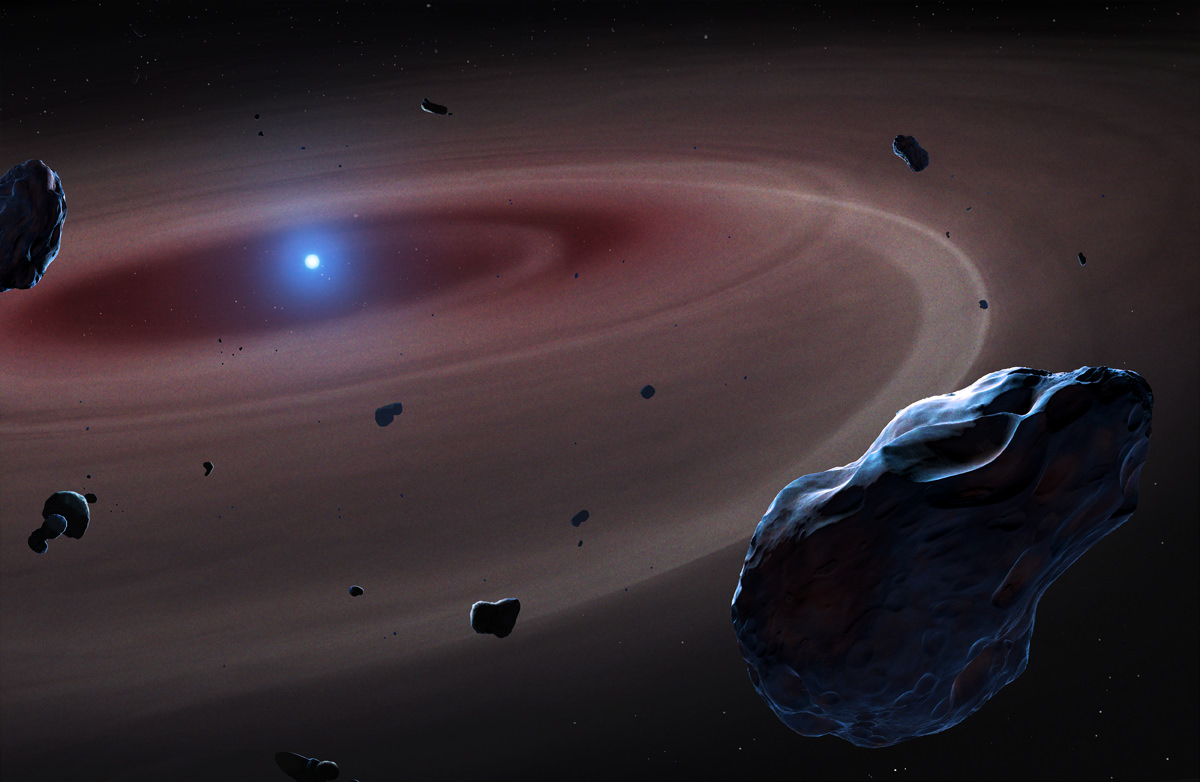

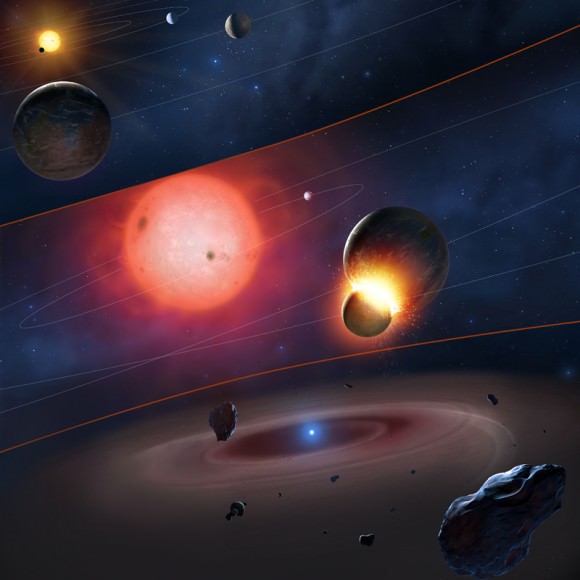

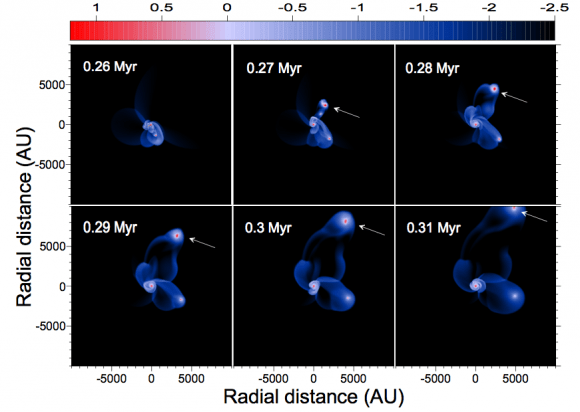

According to research by Shantanu Basu of the University of Western Ontario and Eduard I. Vorobyov from the University of Vienna in Austria and Russia’s Southern Federal University, brown dwarfs may have been flung out of other protostellar disks as they were forming, taking clumps of material with them to complete their development.

Basu and Vorobyov modeled the dynamics of protostellar disks, the clouds of gas and dust that form “real” stars. (Our own solar system formed from one such disk nearly five billion years ago.) What they found was that given enough angular momentum — that is, spin — the disk could easily eject larger clumps of material while still having enough left over to eventually form a star.

The ejected clumps would then continue condensing into a massive object, but never quite enough to begin hydrogen fusion. Rather than stars, they become brown dwarfs — still radiating heat but nothing like a true star. (And they’re not really brown, by the way… they’re probably more of a dull red.)

In fact a single protostellar disk could eject more than one clump during its development, Basu and Vorobyov found, leading to the creation of multiple brown dwarfs.

If this scenario is indeed the way brown dwarfs form, it stands to reason that the Universe may be full of them. Since they are not very luminous and difficult to detect at long distances, the researchers suggest that brown dwarfs may be part of the answer to the dark matter mystery.

“There could be significant mass in the universe that is locked up in brown dwarfs and contribute at least part of the budget for the universe’s missing dark matter,” Basu said. “And the common idea that the first stars in the early universe were only of very high mass may also need revision.”

Based on this hypothesis, with the potential number of brown dwarfs that could be in our galaxy alone we may find that these “failed stars” are actually quite successful after all.

The team’s research paper was accepted on March 1 into The Astrophysical Journal.

Read more on the University of Western Ontario’s news release here.