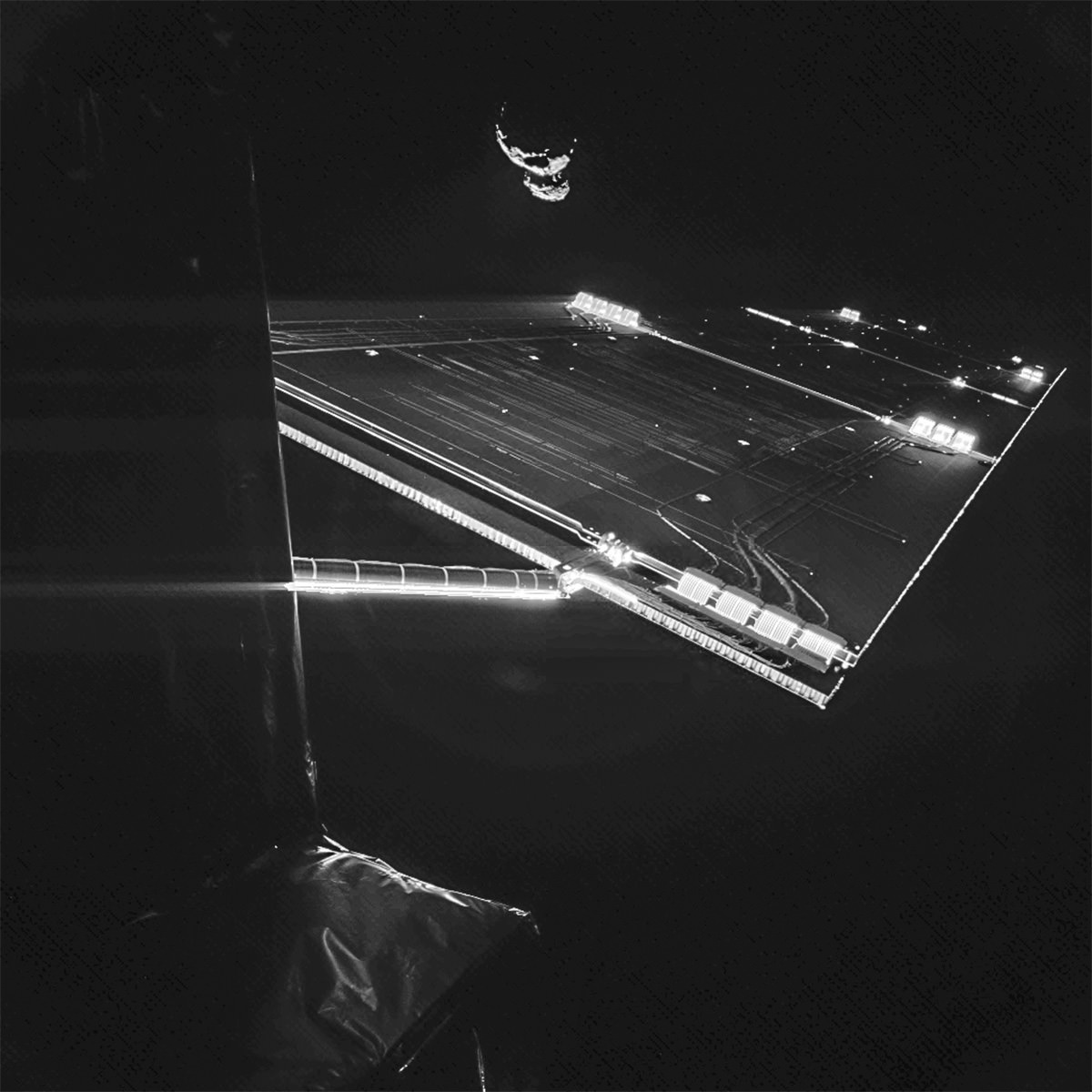

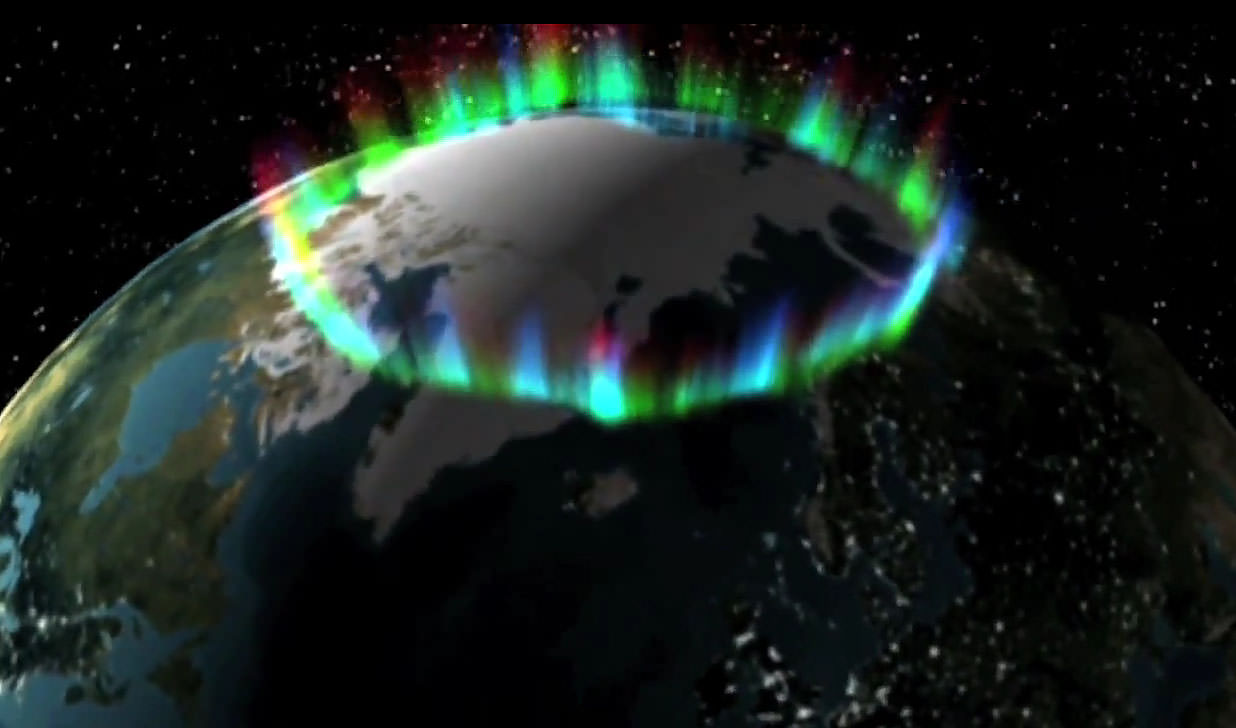

Yes, it’s another time-lapse of the October 8 lunar eclipse that was observed by skywatchers across half the Earth… except that these images weren’t captured from Earth at all; this was the view from Mercury!

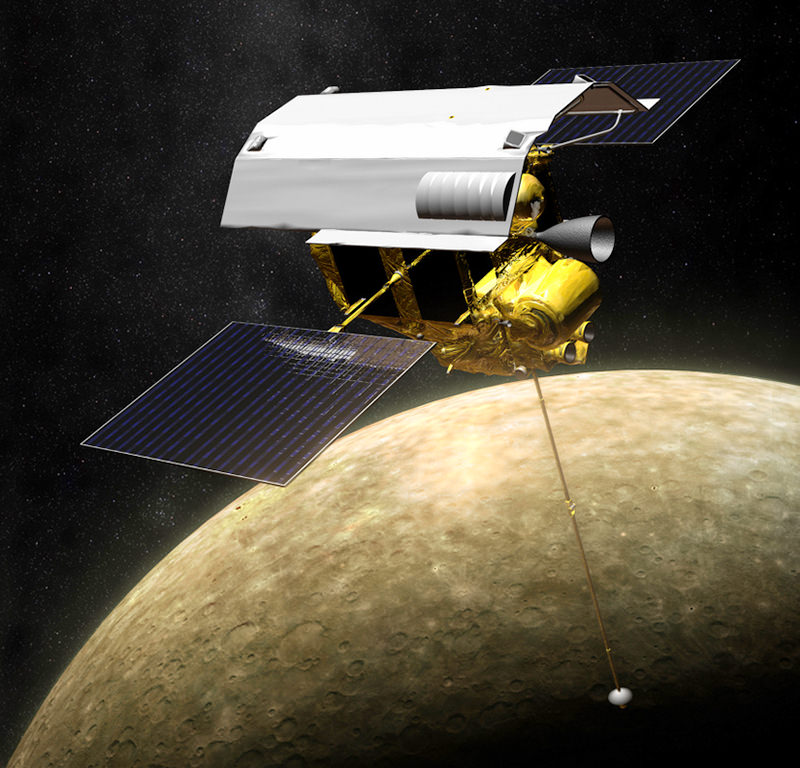

The animation above was constructed from 31 images taken two minutes apart by the MESSENGER spacecraft between 5:18 a.m. and 6:18 a.m. EDT on Oct. 8, 2014.

“From Mercury, the Earth and Moon normally appear as if they were two very bright stars,” said Hari Nair, a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, which developed and operates the MESSENGER mission for NASA. “During a lunar eclipse, the Moon seems to disappear during its passage through the Earth’s shadow, as shown in the movie.”

According to Nair the images have been zoomed by a factor of two and the Moon’s brightness has been increased by a factor of about 25 to enhance visibility. Captured by MESSENGER’s narrow-angle camera, Earth and the Moon were 0.713 AU (106.6 million km / 66.2 million miles) away from Mercury when the images were acquired.

Want to see some great photos of the eclipse shared by talented photographers around the world? Click here.

The Oct. 8 “Hunter’s Moon” eclipse was the second and last total lunar eclipse of 2014. The next will occur on April 4 of next year… but by that time MESSENGER won’t be around to witness it.

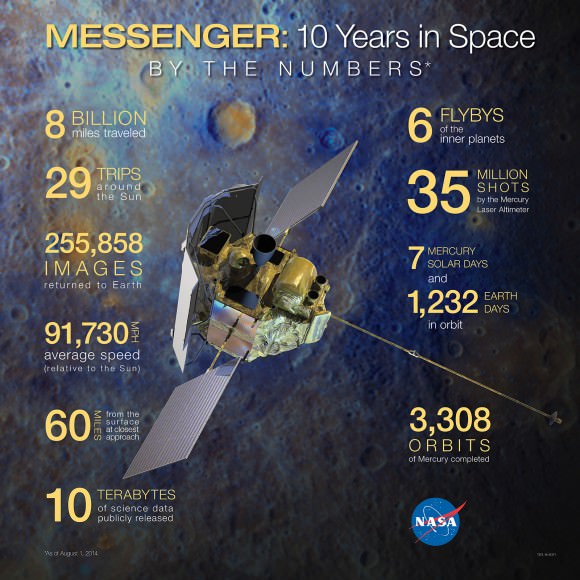

Launched August 3, 2004, MESSENGER entered orbit at Mercury on March 18, 2011. It is currently nearing the end of its missions as well as its its operational life, but we still have several more months of observations to look forward to from around the Solar System’s innermost planet before MESSENGER makes its final pass and ultimately impacts Mercury’s surface in March 2015.

Video credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington

Source: MESSENGER news release