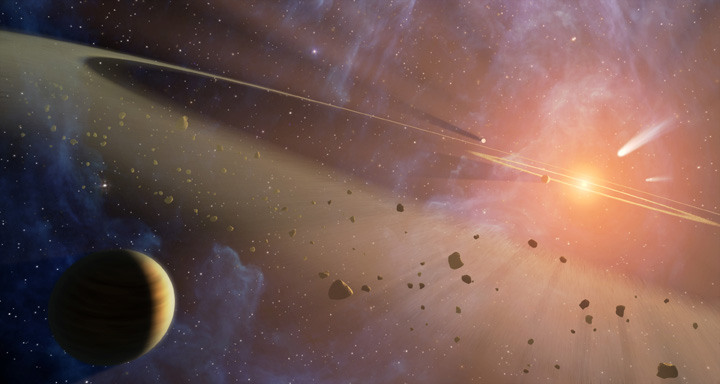

The vast majority of the known exoplanets have been discovered by the radial velocity method. This method employs the effects of a planet’s gentle tug on its parent star which is perceived as a “wobble” in the star’s motion. A new study, conducted by Morais and Correia, looks at whether this effect can be mimicked by another, distinctly non-planetary, source: Binary stars.

Conceptually, the idea is rather straightforward. A star of interest lies in a triple star system. It is the third member and in a larger orbit around a tight binary system. As the tight binary system orbits, there will be periods in which they line up with the star of interest giving a minutely greater pull before relaxing the pull later in their orbit. This remote tug would show a distinctly periodic effect very similar to the effects expected from an inferred planet.

The obvious question was how astronomers could miss the presence of binary stars, close enough to have a notable effect. The authors of the paper suggest that if the binary pair orbited sufficiently close, it would be unlikely that they could be resolved as a binary. Additionally, if one member were sufficiently faint (an M dwarf), it may not appear readily either. Both of these instances are plausible given that some three fourths of nearby main sequence stars are M class, and about half of all stars are in binary system.

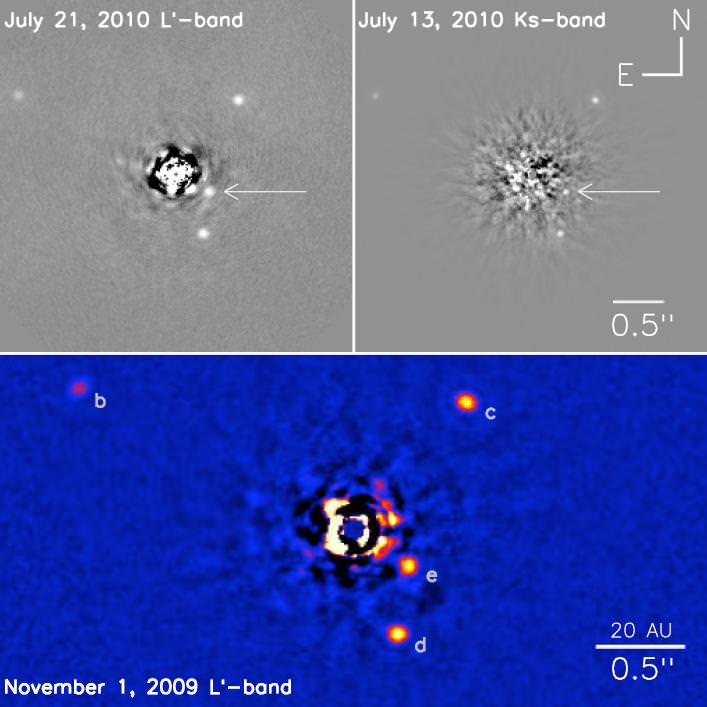

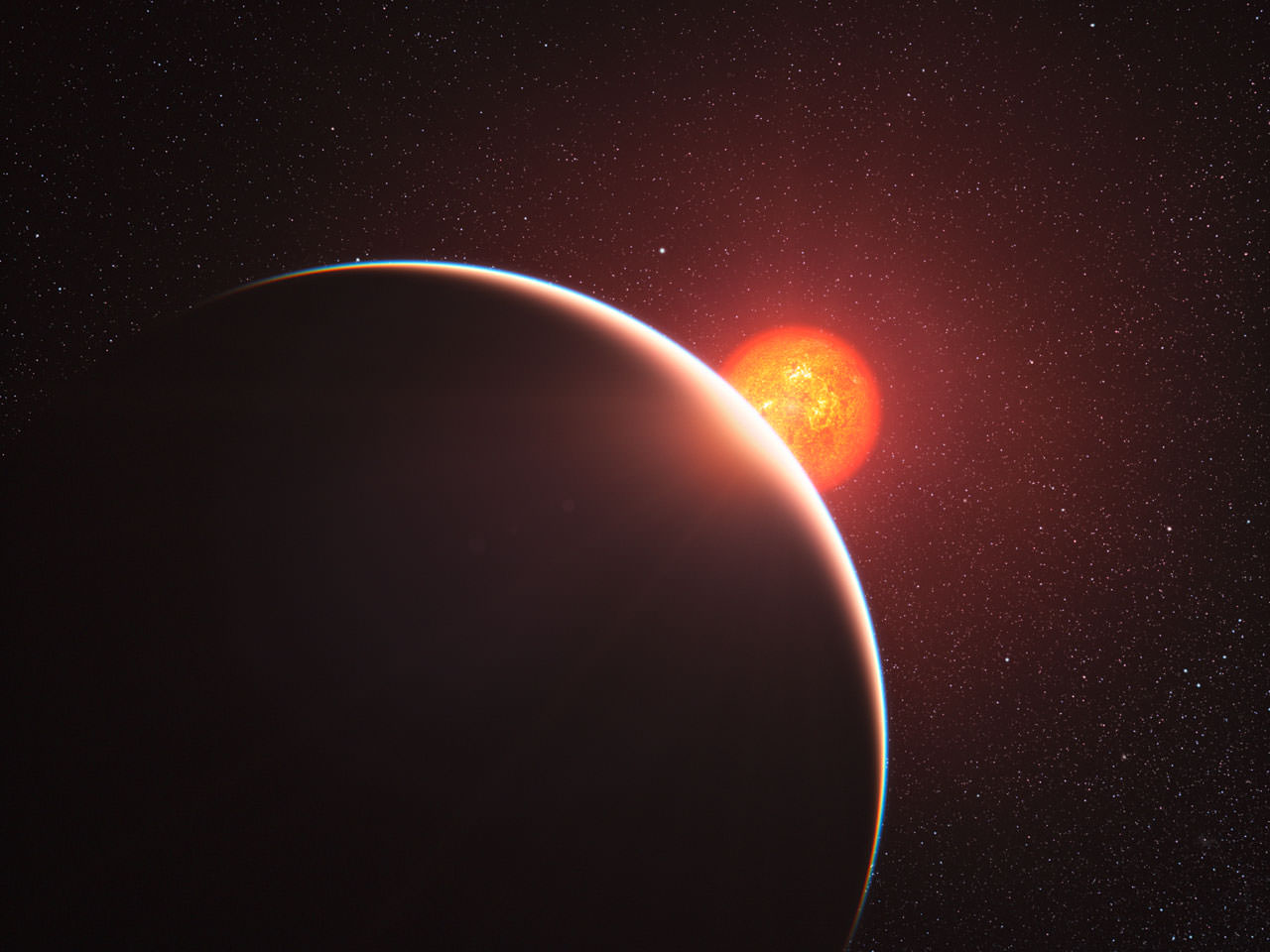

Next, the team asked how important these effects may be. They considered the case of HD 18875, a binary system in which a distant star (A) has a 25.7 year period around a tight binary (Ba + Bb) that orbit each other with a period of 155 days. This system was noteworthy because a hot Jupiter planet was announced around the A star in 2005, but challenged in 2007 when another team could not repeat the observations.

The new study attempted to use their understanding and modeling of three body systems to see if the binary interaction could have produced the spurious signal. Using their model, they determined that the effects of the system itself would have produced effects similar to those of a planet of 4 Earth masses located at 0.38 AU. A planet of such mass is well below the limit of a hot Jupiter and the distance is somewhat larger than usual as well. Thus, the nearby B-binary could not have been responsible. Furthermore, such minute effects of this type are generally interpreted as “super-Earths” and have only become prevalent in observations in the past few years.

Thus, while the unconfirmed planet around HD 18875 A might not have been caused by the nearby binary, the work in this new paper has shown that effects of nearby binaries will become increasingly important as we start detecting radial velocities indicative of less and less massive planets.