Within our own lives, one of the most powerful forces is that of the Sun. Directly or indirectly, it provides all of the energy we use on a daily basis. Yet this mass of incandescent plasma is often a mere afterthought. But not to be forgotten, writer for Astronomy magazine, Bob Berman makes the Sun the focus of a new book, The Sun’s Heartheat which explores how our parent star affects our lives in ways more direct than we might expect. The book is due to be released July 13th, but I got a review copy to tell everyone about.

The book is a short read clocking in at a quick 20 chapters. Roughly the first third of them is a brief history of solar astronomy. Most of this is concentrated on the history of observations of sunspots. It goes through the initial discoveries, the waxing and waning of popularity of sunspots thanks to the Maunder minimum, and Schwabe’s discovery of the cycles.

Once that’s ironed out, we get to what I consider to be the main theme of the book: How does the Sun affect us here on Earth? The first topics addressed are rather germane: The sun brings life, but too much of it can kill you. But after that, the topics are a bit more interesting. There’s a fantastic chapter on the importance of getting adequate supplies of vitamin D which your body produces naturally from exposure to the Sun. Another chapter deals with the way the Sun doesn’t affect us: Astrologically. The book discusses our ability to see colors and the impressiveness of total solar eclipses and auroras.

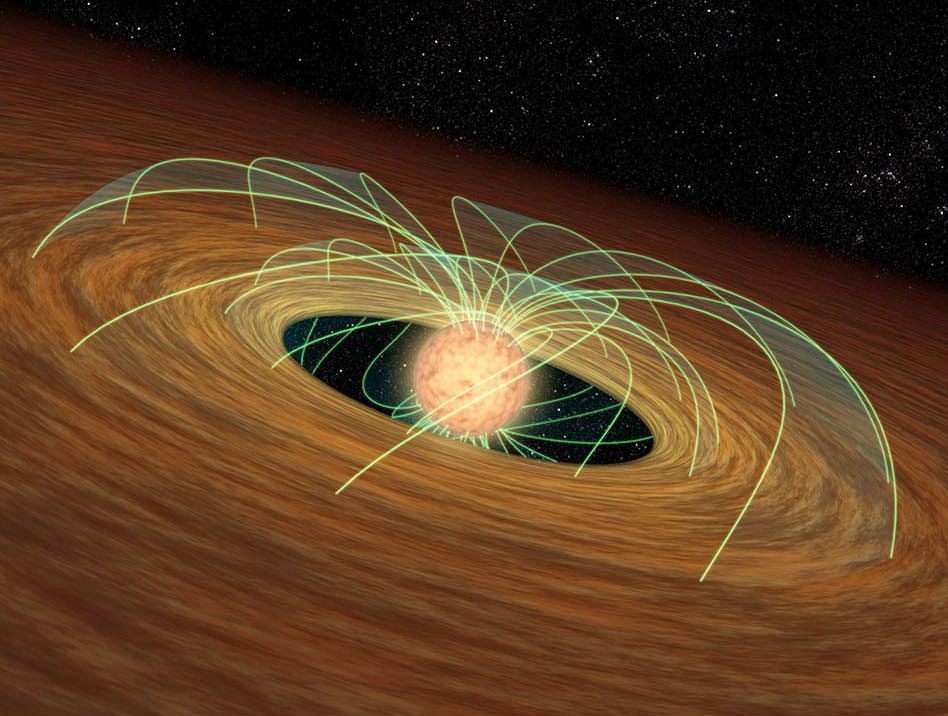

The second to last chapter covers just how much peril we face from a large coronal mass ejection. I was familiar with nearly everything in the book, including this chapter, but I think this chapter was my favorite. Sadly, most people are disinterested in science, but more than any other, this one was tangible enough to be rather alarming.

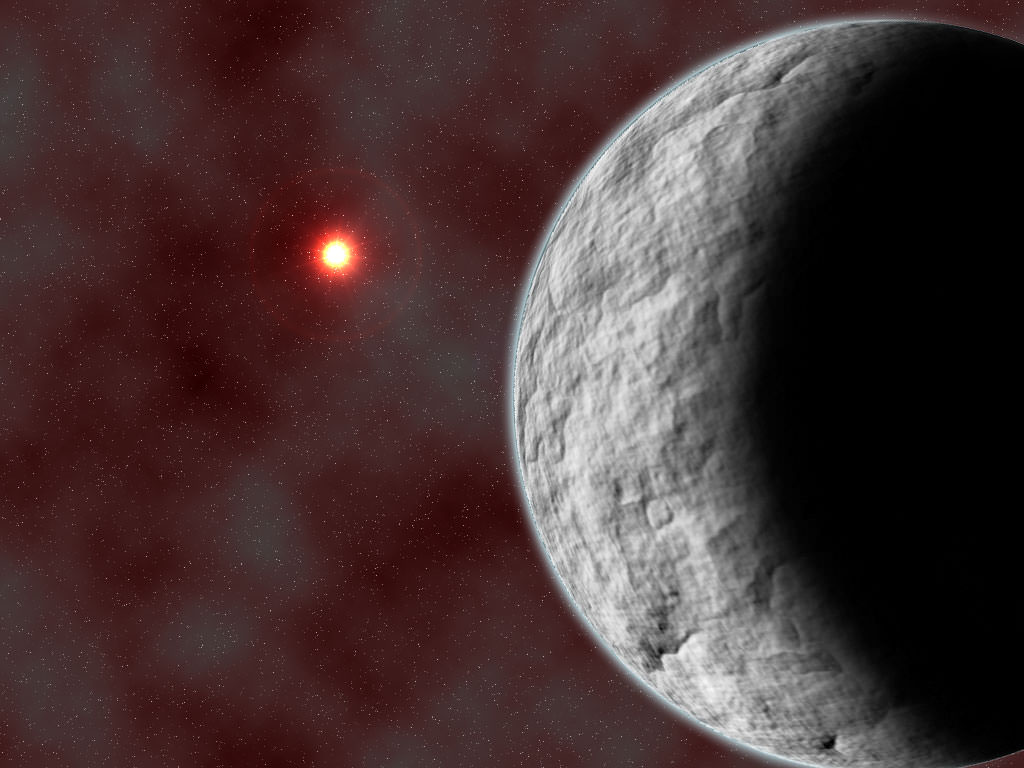

It closes with a preview of the future Sun, describing how its slow increase in brightness will make life on Earth unfavorable in a billion years or so and how it will eventually expand into a red giant.

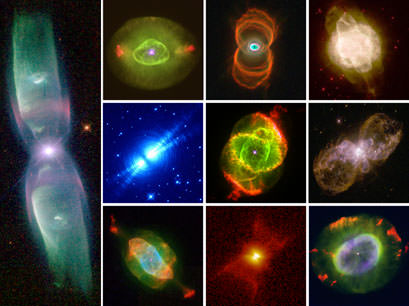

If you’re an experienced astronomy enthusiast, this book will likely offer little new information on the Sun itself, although it does have lots of good backstories on some of the discoveries and those involved. It is engaging thanks to a friendly tone, even if Berman does have an odd fascination with anachronisms (17th century HMO’s?). The book lacked several of the deeper topics that I feel could have been more inviting for advanced readers such as a more thorough description of our knowledge of the innards of the Sun thanks to helioseismology. I suspect this is because it didn’t relate strongly enough to the main thesis aside from a general, how the Sun works which doesn’t focus on how it affects us.

But if you know a young astronomer, or someone older just getting into the field, or someone that’s stared only at deep sky objects and never thought much about the closest star to home, this book would likely be of some interest.