The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is already making great strides in helping us to unravel the mysteries of the Universe. Earlier this year, hundreds of rogue planets were discovered in the Orion Nebula. The real surprise to this discovery was that 9% of the planets were paired up in wide binary pairs. To understand how this binary planets formed, astronomers simulated various scenarios for their formation.

Continue reading “What’s the Source of Binary Rogue Planets?”Dark Matter Could Cause Jupiter’s Night Side to Glow

One of the aspects of our study of the universe that fascinates me is the hunt for dark matter. That elusive material that doesn’t interact with much makes it difficult but not impossible to detect. Gravitational lenses are one such phenomena that point to its existence indeed it allows us to estimate how much there is in galaxy clusters. A paper now suggests that observations of Jupiter by Cassini in 2000 suggest we may be able to detect it using planets too.

Continue reading “Dark Matter Could Cause Jupiter’s Night Side to Glow”DART Showed We Can Move an Asteroid. Can We Do It More Efficiently?

Like many of you, I loved Deep Impact and Armageddon. Great films, loads of action and of course, an asteroid on collision course with Earth. What more is there to love! Both movies touched upon the options for humanity to try and avoid such a collision but the reality is a little less Hollywood. One of the most common options is to try some sort of single impact style event as was demonstrated by the DART (Double Asteroid Redirection Test) mission but a new paper offer an intriguing and perhaps more efficient alternative.

Continue reading “DART Showed We Can Move an Asteroid. Can We Do It More Efficiently?”Planets Orbiting Pulsars Should Have Strange and Beautiful Auroras. And We Could Detect Them

We have been treated to some amazing aurora displays over recent months. The enigmatic lights are caused by charged particles from the Sun rushing across space and on arrival, causing the gas in the atmosphere to glow. Now researchers believe that even on exoplanets around pulsars we may just find aurora, and they may even be detectable.

Continue reading “Planets Orbiting Pulsars Should Have Strange and Beautiful Auroras. And We Could Detect Them”Solar Storms Could Cause Mayhem to Trains

The rail service here in the UK is often the brunt of jokes. If it’s not the wrong type of rain, or the leaves are laying on the tracks the wrong way then it’s some other seemingly ludicrous reason that the trains are delayed, or even cancelled. A recent study by scientists at the University of Lancaster suggest that even the solar wind might cause train signals to be incorrectly triggered with potentially disastrous consequences.

Continue reading “Solar Storms Could Cause Mayhem to Trains”15 Years of Data Reveal the Events Leading Up to Betelgeuse’s “Great Dimming”

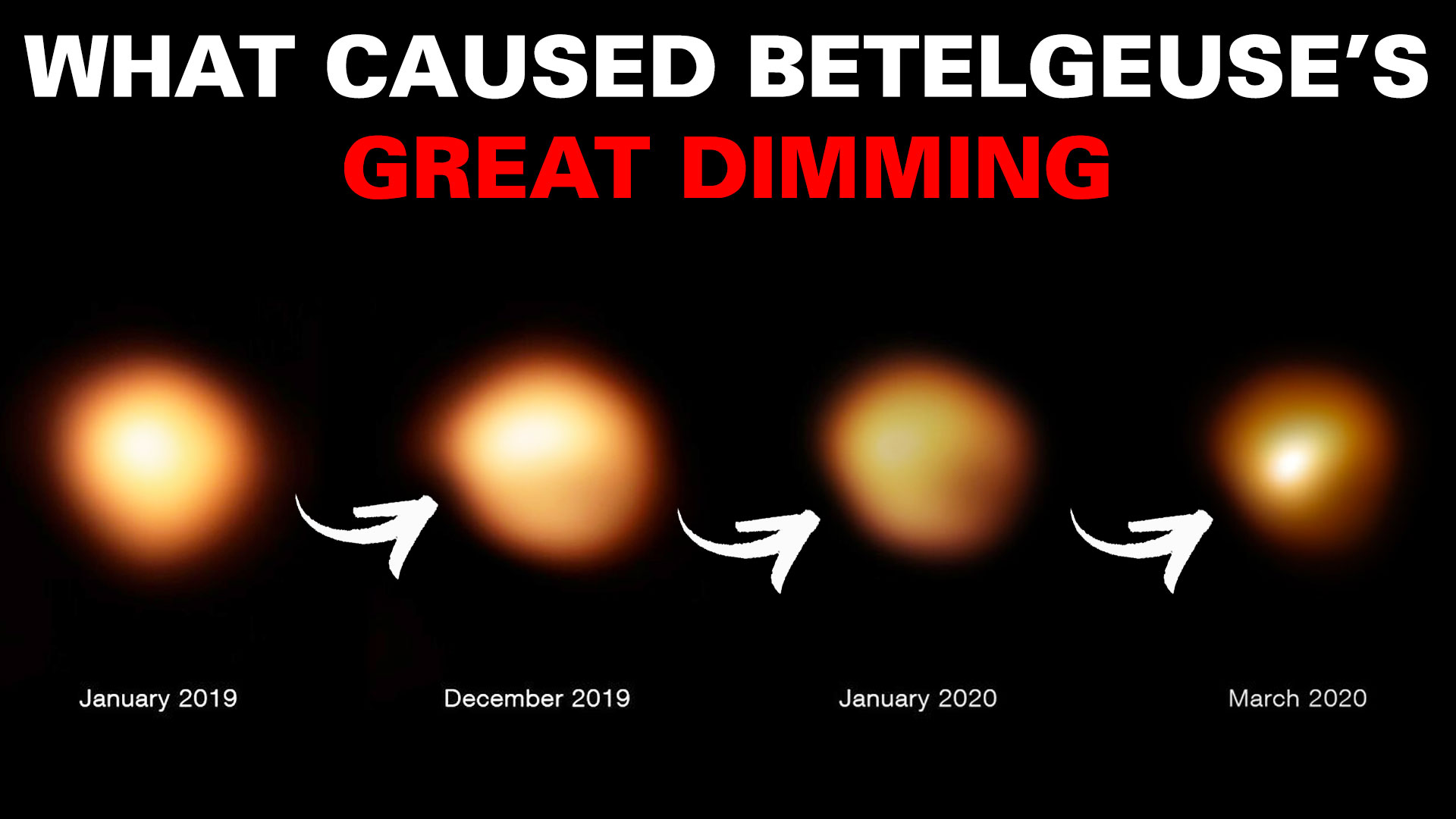

Anyone who regularly watches the skies may well be familiar with the constellation Orion the hunter. It is one of the few constellations that actually looks like the thing it is supposed to look like rather than some abstract resemblance. One prominent star is Betelgeuse and back in 2020 it dimmed to a level lower than ever before in recorded history. A team of astronomers have been studying the event with some fascinating results.

Continue reading “15 Years of Data Reveal the Events Leading Up to Betelgeuse’s “Great Dimming””What Could a Next Generation Event Horizon Telescope Do?

Telescopes have come a long way in a little over four hundred years! It was 1608 that Dutch spectacle maker Hans Lippershey who was said to be working with a case of myopia and, in working with lenses discovered the magnifying powers if arranged in certain configurations. Now, centuries on and we have many different telescope designs and even telescopes in orbit but none are more incredible than the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT). Images las year revealed the supermassive black hole at the centre of our Galaxy and around M87 but now a team of astronomers have explored the potential of an even more powerful system the Next Generation EHT (ngEHT).

Continue reading “What Could a Next Generation Event Horizon Telescope Do?”Iran Sent a Capsule Capable of Holding Animals into Orbit.

Despite popular opinion, the first animals in space were not dogs or chimps, they were fruit flies launched by the United States in February 1947. The Soviet Union launched Laika, the first dog into space in November 1957 and now, it seems Iran is getting in on the act. A 500kg capsule known as the “indigenous bio-capsule” with life support capability was recently launched atop the Iranian “Salman” rocket. It has been reported by some agencies that there were animals on board but no official statement has been released.

Continue reading “Iran Sent a Capsule Capable of Holding Animals into Orbit.”Another Fast Radio Burst is Coming from a Hypernebula. Also, Hypernebulae are a Thing

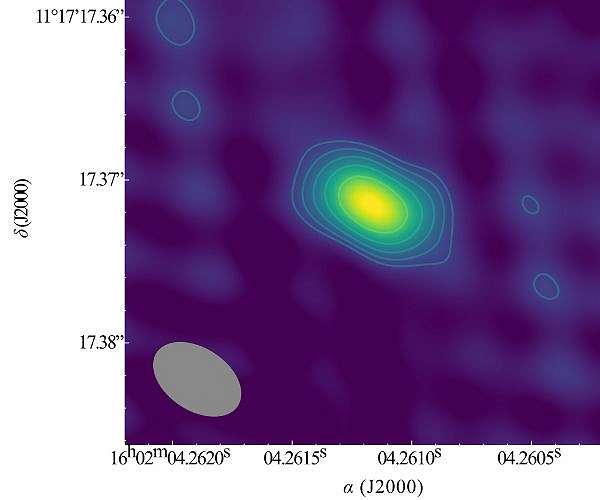

If nothing else catches your attention in the title then surely ‘hypernebula’ does! There are some amazing processes scattered around the cosmos, of particular interest are the fast radio bursts (FRB). These brief flashes of radiation happen without warning…until now. A team in the Netherlands have identified a second FRB as coming from within a hyper nebula – a dense and highly magnetised cloud of plasma that is illuminated by a powerful but unknown source!

Continue reading “Another Fast Radio Burst is Coming from a Hypernebula. Also, Hypernebulae are a Thing”Will Wide Binaries Be the End of MOND?

It’s a fact that many of us have churned out during public engagement events; that at least 50% of all stars are part of binary star systems. Some of them are simply stunning to look at, others present headaches with complex orbits in multiple star systems. Now it seems wide binary stars are starting to shake the foundations of physics as they question the very theory of gravity.

Continue reading “Will Wide Binaries Be the End of MOND?”