For millennia, human beings stared up at the night sky and were held in awe by the Moon. To many ancient cultures, it represented a deity, and its cycles were accorded divine significance. By the time of Classical Antiquity and the Middle Ages, the Moon was considered to be a heavenly body that orbited Earth, much like the other known planets of the day (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn).

However, our understanding of moons was revolutionized when in 1610, astronomer Galileo Galilei pointed his telescope to Jupiter and noticed ” four wandering stars” around Jupiter. From this point onward, astronomers have come to understand that planets other than Earth can have their own moons – in some cases, several dozen or more. So just how many moons are there in the Solar System?

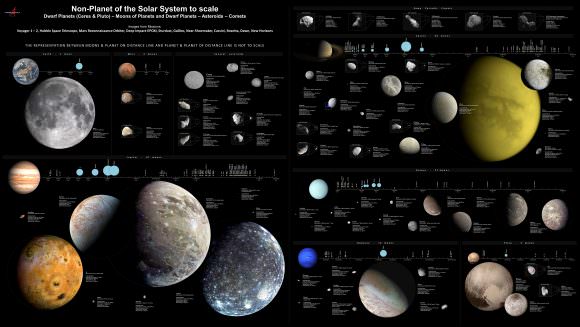

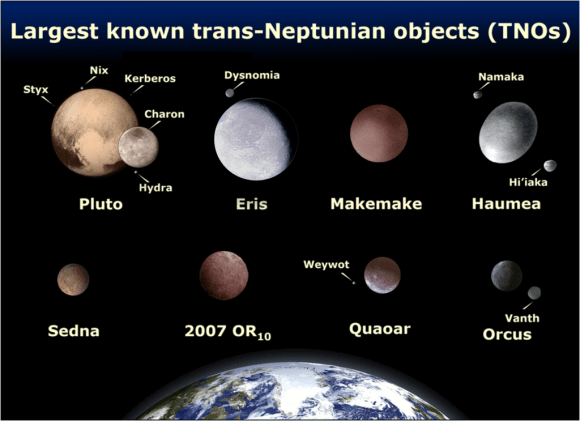

In truth, answering that question requires a bit of clarification first. If we are talking about confirmed moons that orbit any of the planets of the Solar System (i.e. those that are consistent with the definition adopted by the IAU in 2006), then we can say that there are currently 207 known moons. If however, we open the floor to “dwarf planets” that have confirmed satellites, the number reached 220.

However, 479 minor-planet moons have also been observed in the Solar System (as of Dec. 2022). This includes the 229 known objects in the asteroid belt with satellites, six Jupiter Trojans, 91 near-Earth objects (two with two satellites each), 31 Mars-crossers, and 84 natural satellites of Trans-Neptunian Objects. And some 150 additional small bodies have been observed within the rings of Saturn. If we include all these, then we can say that the Solar System has 849 known satellites.

Inner Solar System:

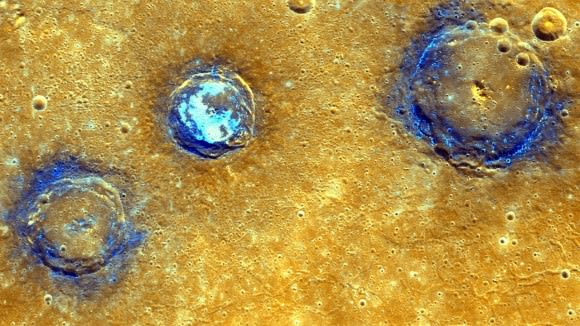

The planets of the Inner Solar system – Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars – are all terrestrial planets, which means that they are composed of silicate rock and minerals that are differentiated between a metallic core and a silicate mantle and crust. For a number of reasons, few satellites exist within this region of the Solar System.

All told, only three natural satellites exist orbiting planetary bodies in the Inner Solar System – Earth and Mars. While scientists theorize that there were moons around Mercury and Venus in the past, it is believed that these moons impacted the surface a long time ago. The reason for this sparseness of satellites has a lot to do with the gravitational influence of the Sun.

Both Mercury and Venus are too close to the Sun to have grabbed onto a passing object or held onto rings of debris in orbit that could have coalesced to form a satellite over time. In Mercury’s case, it is also too weak in terms of its own gravitational pull to grab a satellite in its orbit. Earth and Mars were able to retain satellites, but mainly because they are the outermost of the Inner planets.

Earth has only one natural satellite, which we are familiar with – the Moon. With a mean radius of 1737 km (1,080 mi) and a mass of 7.3477 x 10²² kg, the Moon is 0.273 times the size of Earth and 0.0123 as massive, which is quite large for a satellite. It is also the second densest moon in our Solar System (after Io), with a mean density of 3.3464 g/cm³.

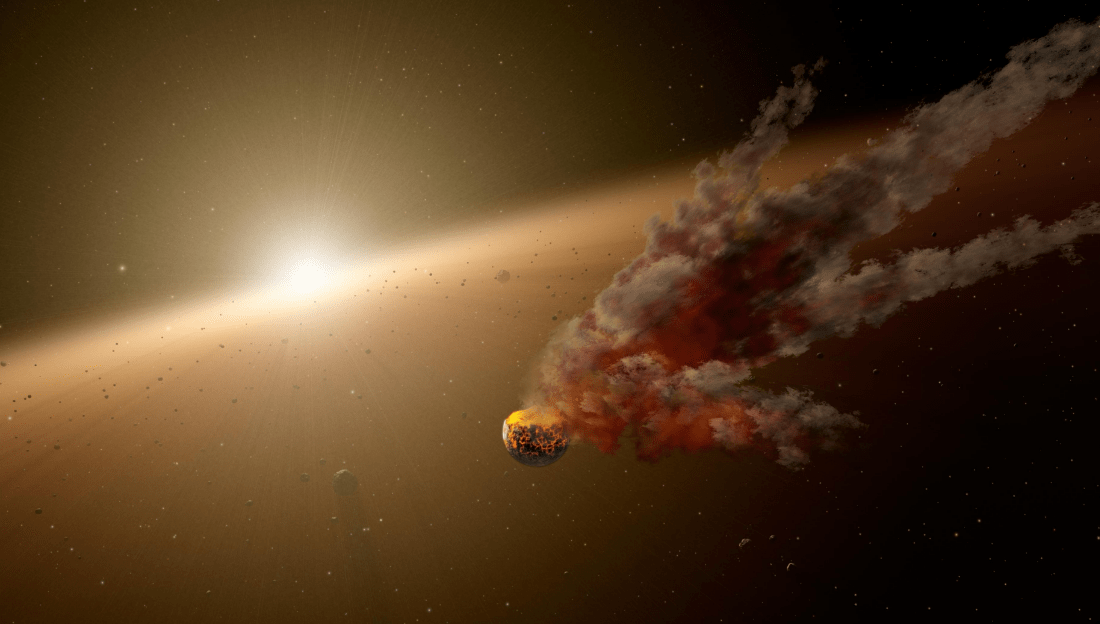

Several theories have been proposed for the formation of the Moon. The prevailing hypothesis today is that the Earth-Moon system formed as a result of an impact between the newly-formed proto-Earth and a Mars-sized object (named Theia) roughly 4.5 billion years ago. This impact would have blasted material from both objects into orbit, where it eventually accreted to form the Moon.

Mars, meanwhile, has two moons – Phobos and Deimos. Like our own Moon, both of the Martian moons are tidally locked to Mars, so they always present the same face to the planet. Compared to our Moon, they are rough and asteroid-like in appearance and also much smaller. Hence the prevailing theory is that they were once asteroids that were kicked out of the Main Belt by Jupiter’s gravity and were then acquired by Mars.

The larger moon is Phobos, whose name comes from the Greek word which means “fear” (i.e. phobia). Phobos measures just 22.7 km (14 mi) across and has an orbit that places it closer to Mars than Deimos. Compared to Earth’s own Moon — which orbits at a distance of 384,403 km (238,857 mi) away from our planet — Phobos orbits at an average distance of only 9,377 km (5,826.5 mi) above Mars.

Mars’ second moon is Deimos, which takes its name from the Greek word for panic. It is even smaller, measuring just 12.6 km (7.83 mi) across, and is also less irregular in shape. Its orbit places it much farther away from Mars, at a distance of 23,460 km (14,577 mi), which means that Deimos takes 30.35 hours to complete an orbit around Mars.

These three moons are the sum total of moons to be found within the Inner Solar System (at least, by the conventional definition). But looking further abroad, we see that this is really just the tip of the iceberg. To think we once believed that the Moon was the only one of its kind!

Outer Solar System:

Beyond the Asteroid Belt (and Frost Line), things become quite different. In this region of the Solar System, every planet has a substantial system of Moons; in the case of Jupiter and Saturn, reaching perhaps even into the hundreds. So far, a total of 213 moons have been confirmed orbiting the Outer Planets, while several hundred more orbit minor bodies and asteroids.

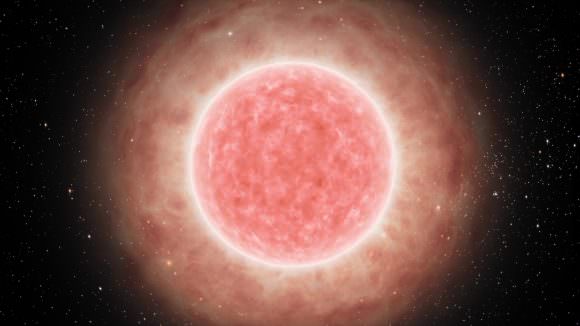

Due to its immense size, mass, and gravitational pull, Jupiter has the most satellites of any planet in the Solar System. At present, the Jovian system includes 80 known moons, though it is estimated that it may have over 200 moons and moonlets (the majority of which are yet to be confirmed and classified).

The four largest Jovian moons are known as the Galilean Moons (named after their discoverer, Galileo Galilei). They include Io, the most volcanically active body in our Solar System; Europa, which is suspected of having a massive subsurface ocean; Ganymede, the largest moon in our Solar System; and Callisto, which is also thought to have a subsurface ocean and features some of the oldest surface material in the Solar System.

Then there’s the Inner Group (or Amalthea group), which is made up of four small moons that have diameters of less than 200 km (124 mi), orbit at radii less than 200,000 km (124,275 mi), and have orbital inclinations of less than half a degree. This group includes the moons of Metis, Adrastea, Amalthea, and Thebe. Along with a number of as-yet-unseen inner moonlets, these moons replenish and maintain Jupiter’s faint ring system.

Jupiter also has an array of Irregular Satellites, which are substantially smaller and have more distant and eccentric orbits than the others. These moons are broken down into families that have similarities in orbit and composition and are believed to be largely the result of collisions from large objects that were captured by Jupiter’s gravity.

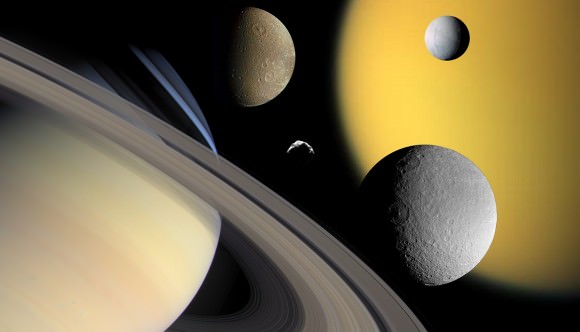

Similar to Jupiter, it is estimated that Saturn has at least 150 moons and moonlets, but only 83 of these moons have been given official names or designations. Of these, 57 are less than 10 km (6.2 mi) in diameter, and another 13 are between 10 and 50 km (6.2 to 31 mi) in diameter. However, some of its inner and outer moons are rather large, ranging from 250 to over 5000 km (155 to 3100 mi)

Traditionally, most of Saturn’s moons have been named after the Titans of Greek mythology and are grouped based on their size, orbits, and proximity to Saturn. The innermost moons and regular moons all have small orbital inclinations and eccentricities and prograde orbits. Meanwhile, the irregular moons in the outermost regions have orbital radii of millions of kilometers, orbital periods lasting several years, and move in retrograde orbits.

The Inner Large Moons, which orbit within the E Ring, include the larger satellites Mimas Enceladus, Tethys, and Dione. These moons are all composed primarily of water ice and are believed to be differentiated into a rocky core and an icy mantle and crust. The Large Outer Moons, which orbit outside of Saturn’s E Ring, are similar in composition to the Inner Moons – i.e. composed primarily of water ice, and rock.

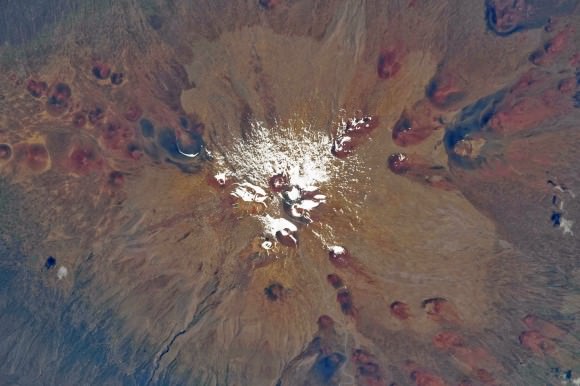

At 5,150 km (3,200 mi) in diameter and 1,350×1020 kg in mass, Titan is Saturn’s largest moon and comprises more than 96% of the mass in orbit around the planet. Titan is also the only large moon to have its own atmosphere, which is cold, dense, and composed primarily of nitrogen with a small fraction of methane. Scientists have also noted the presence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the upper atmosphere, as well as methane ice crystals.

The surface of Titan, which is difficult to observe due to persistent atmospheric haze, shows only a few impact craters, evidence of cryo-volcanoes, and longitudinal dune fields that were apparently shaped by tidal winds. Titan is also the only body in the Solar System aside from Earth to have bodies of liquid on its surface. These take the form of methane–ethane lakes in Titan’s north and south polar regions.

Uranus has 27 known satellites, which are divided into the categories of larger moons, inner moons, and irregular moons (similar to other gas giants). The largest moons of Uranus are, in order of size, Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Oberon, and Titania. These moons range in diameter and mass from 472 km (293 mi) and 6.7×1019 kg for Miranda to 1578 km (980.5 mi) and 3.5×1021 kg for Titania. Each of these moons is particularly dark, with low bond and geometric albedos. Ariel is the brightest, while Umbriel is the darkest.

All of the large moons of Uranus are believed to have formed in the accretion disc, which existed around Uranus for some time after its formation or resulted from the large impact suffered by Uranus early in its history. Each one is comprised of roughly equal amounts of rock and ice, except for Miranda, which is made primarily of ice.

The ice component may include ammonia and carbon dioxide, while the rocky material is believed to be composed of carbonaceous material, including organic compounds (similar to asteroids and comets). Their compositions are believed to be differentiated, with an icy mantle surrounding a rocky core.

Neptune has 14 known satellites, all but one of which are named after Greek and Roman deities of the sea (except for S/2004 N 1, which is currently unnamed). These moons are divided into two groups – the regular and irregular moons – based on their orbit and proximity to Neptune. Neptune’s Regular Moons – Naiad, Thalassa, Despina, Galatea, Larissa, S/2004 N 1, and Proteus – are those that are closest to the planet and which follow circular, prograde orbits that lie in the planet’s equatorial plane.

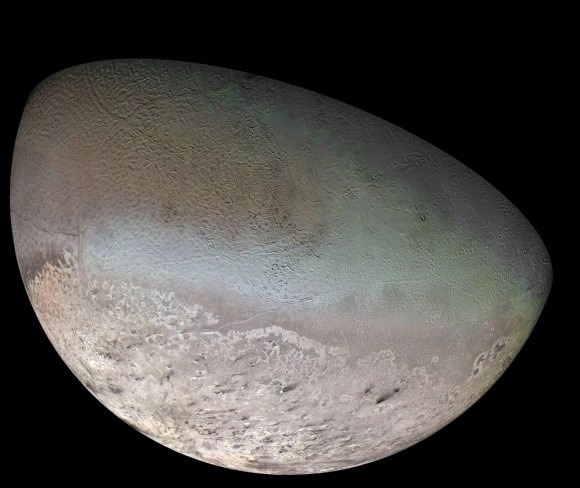

Neptune’s irregular moons consist of the planet’s remaining satellites (including Triton). They generally follow inclined eccentric and often retrograde orbits far from Neptune. The only exception is Triton, which orbits close to the planet, following a circular orbit, though retrograde and inclined.

In order of their distance from the planet, the irregular moons are Triton, Nereid, Halimede, Sao, Laomedeia, Neso, and Psamathe – a group that includes both prograde and retrograde objects. With the exception of Triton and Nereid, Neptune’s irregular moons are similar to those of other giant planets and are believed to have been gravitationally captured by Neptune.

With a mean diameter of around 2,700 km (1,678 mi) and a mass of 21,4080 ± 520×1017 kg, Triton is the largest of Neptune’s moons and the only one large enough to achieve hydrostatic equilibrium (i.e. is spherical in shape). At a distance of 354,759 km (220,437 mi) from Neptune, it also sits between the planet’s inner and outer moons.

These moons make up the lion’s share of natural satellites found in the Solar System. However, thanks to ongoing exploration and improvements made in our instrumentation, satellites are being discovered in orbit around minor bodies as well.

Dwarf Planets and Other Bodies:

As already noted, there are several dwarf planets, TNOs, and other bodies in the Solar System that also have their own moons. These consist mainly of the natural satellites that have been confirmed orbiting Pluto, Eris, Haumea, and Makemake. With five orbiting satellites, Pluto has the most confirmed moons (though that may change with further observation).

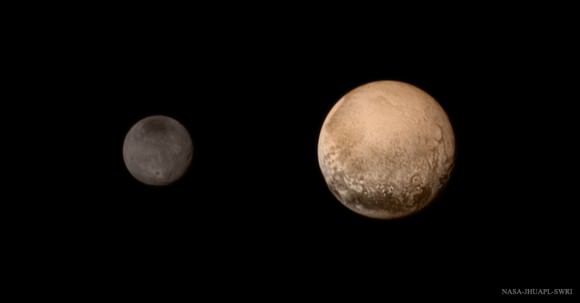

The largest and closest in orbit to Pluto is Charon. This moon was first identified in 1978 by astronomer James Christy using photographic plates from the United States Naval Observatory (USNO) in Washington, D.C. Beyond Charon lies the four other circumbinary moons – Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra, respectively.

Nix and Hydra were discovered simultaneously in 2005 by the Pluto Companion Search Team using the Hubble Space Telescope. The same team discovered Kerberos in 2011. The fifth and final satellite, Styx, was discovered by the New Horizons spacecraft in 2012 while capturing images of Pluto and Charon.

Charon, Styx, and Kerberos are all massive enough to have collapsed into a spheroid shape under their own gravity. Nix and Hydra, meanwhile, are oblong in shape. The Pluto-Charon system is unusual since it is one of the few systems in the Solar System whose barycenter lies above the primary’s surface. In short, Pluto and Charon orbit each other, causing some scientists to claim that it is a “double-dwarf system” instead of a dwarf planet and an orbiting moon.

In addition, it is unusual in that each body is tidally locked to the other. Charon and Pluto always present the same face to each other, and from any position on either body, the other is always at the same position in the sky or always obscured. This also means that the rotation period of each is equal to the time it takes the entire system to rotate around its common center of gravity.

In 2007, observations by the Gemini Observatory of patches of ammonia hydrates and water crystals on the surface of Charon suggested the presence of active cryo-geysers. This would seem to indicate that Pluto has a warm subsurface ocean and that the core is geologically active. Pluto’s moons are believed to have been formed by a collision between Pluto and a similar-sized body early in the history of the Solar System. The collision released material that consolidated into the moons around Pluto.

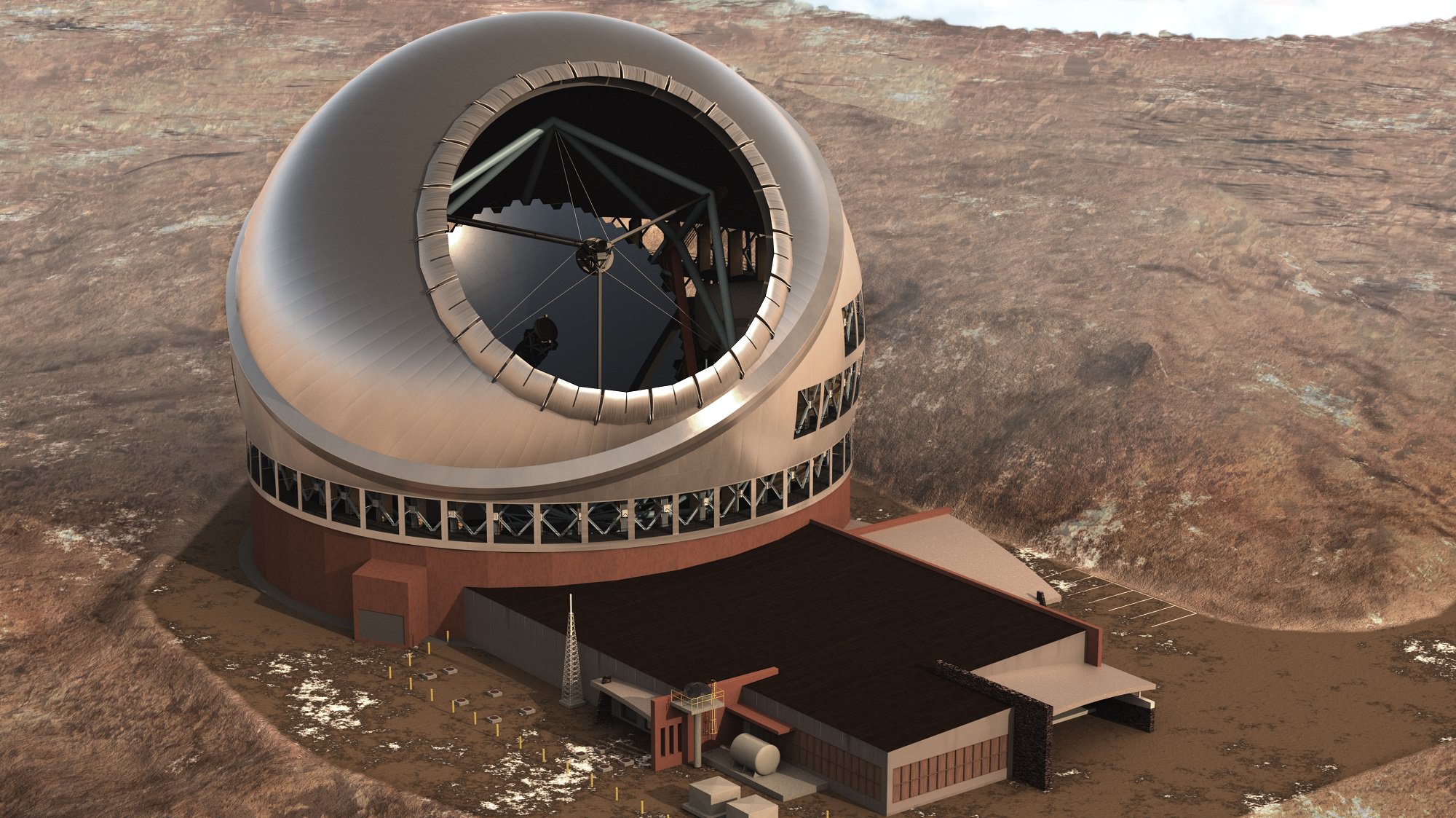

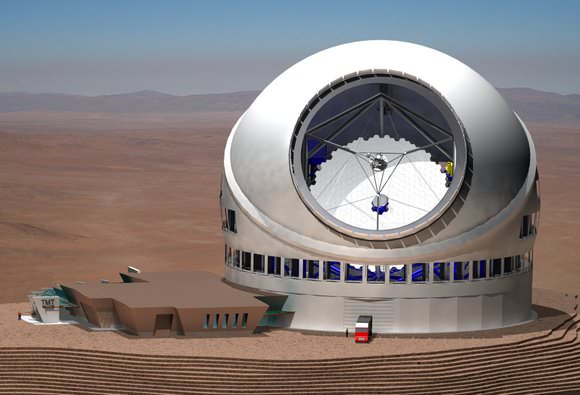

Coming in second is Haumea, which has two known moons – Hi’iaka and Namaka – which are named after the daughters of the Hawaiian goddess. Both were discovered in 2005 by Brown’s team while conducting observations of Haumea at the W.M. Keck Observatory. Hi’iaka, which was initially nicknamed “Rudolph” by the Caltech team, was discovered on January 26th, 2005.

It is the outer, the larger (at roughly 310 km (mi) in diameter), and brighter of the two, and orbits Haumea in a nearly circular path every 49 days. Infrared observations indicate that its surface is almost entirely covered by pure crystalline water ice. Because of this, Brown and his team have speculated that the moon is a fragment of Haumea that broke off during a collision.

Namaka, the smaller and innermost of the two, was discovered on June 30th, 2005, and nicknamed “Blitzen”. It is a tenth the mass of Hi‘iaka and orbits Haumea in 18 days in a highly elliptical orbit. Both moons circle Haumea is highly eccentric orbits. No estimates have been made yet as to their mass.

Eris has one moon called Dysnomia, named after the daughter of Eris in Greek mythology, and was first observed on September 10th, 2005 – a few months after the discovery of Eris. The moon was spotted by a team using the Keck telescopes in Hawaii, who were busy carrying out observations of the four brightest TNOs (Pluto, Makemake, Haumea, and Eris) at the time.

In April 2016, observations using the Hubble Space Telescope‘s Wide Field Camera 3 revealed that Makemake had a natural satellite – which was designated S/2015 (136472) 1 (nicknamed MK 2 by the discovery team). It is estimated to be 175 km (110 mi) km in diameter and has a semi-major axis at least 21,000 km (13,000 mi) from Makemake.

Largest and Smallest Moons:

The title of “largest moon in the Solar System” goes to Ganymede, which measures 5,262.4 kilometers (3,270 mi) in diameter. This not only makes it larger than Earth’s Moon but larger even than the planet Mercury – though it has only half of Mercury’s mass. As for the smallest satellite, that is a tie between S/2003 J 9 and S/2003 J 12. These two satellites, both of which orbit Jupiter, measure about 1 km (0.6 mi) in diameter.

An important thing to note when discussing the number of known moons in the Solar System is that the key word here is “known”. With every passing year, more satellites are being confirmed, and the vast majority of those we now know about were only discovered in the past few decades. As our exploration efforts continue and our instruments improve, we may find that there are hundreds more lurking around out there!

We have written many interesting articles about the moons of the Solar System here at Universe Today. Here’s What is the Biggest moon in the Solar System? What are the Planets of the Solar System?, How Many Moons Does Earth Have?, How Many Moons Does Mars Have?, How Many Moons Does Jupiter Have?, How Many Moons Does Saturn Have?, How Many Moons Does Uranus Have?, How Many Moons Does Neptune Have?

For more information, be sure to check out NASA’s Solar System Exploration page.

We have recorded a whole series of podcasts about the Solar System at Astronomy Cast. Check them out here.

Sources: