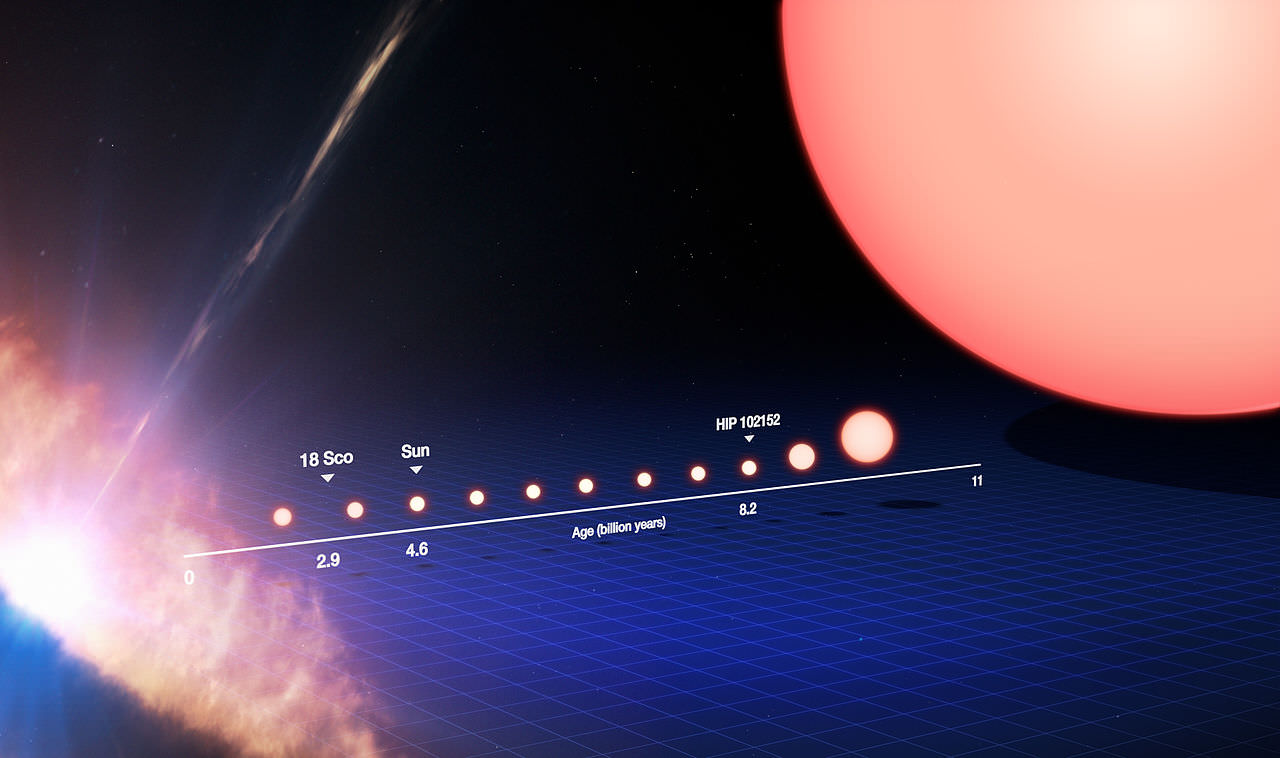

The Sun has always been the center of our cosmological systems. But with the advent of modern astronomy, humans have become aware of the fact that the Sun is merely one of countless stars in our Universe. In essence, it is a perfectly normal example of a G-type main-sequence star (G2V, aka. “yellow dwarf”). And like all stars, it has a lifespan, characterized by a formation, main sequence, and eventual death.

This lifespan began roughly 4.6 billion years ago, and will continue for about another 4.5 – 5.5 billion years, when it will deplete its supply of hydrogen, helium, and collapse into a white dwarf. But this is just the abridged version of the Sun’s lifespan. As always, God (or the Devil, depending on who you ask) is in the details!

To break it down, the Sun is about half way through the most stable part of its life. Over the course of the past four billion years, during which time planet Earth and the entire Solar System was born, it has remained relatively unchanged. This will stay the case for another four billion years, at which point, it will have exhausted its supply of hydrogen fuel. When that happens, some pretty drastic things will take place!

The Birth of the Sun:

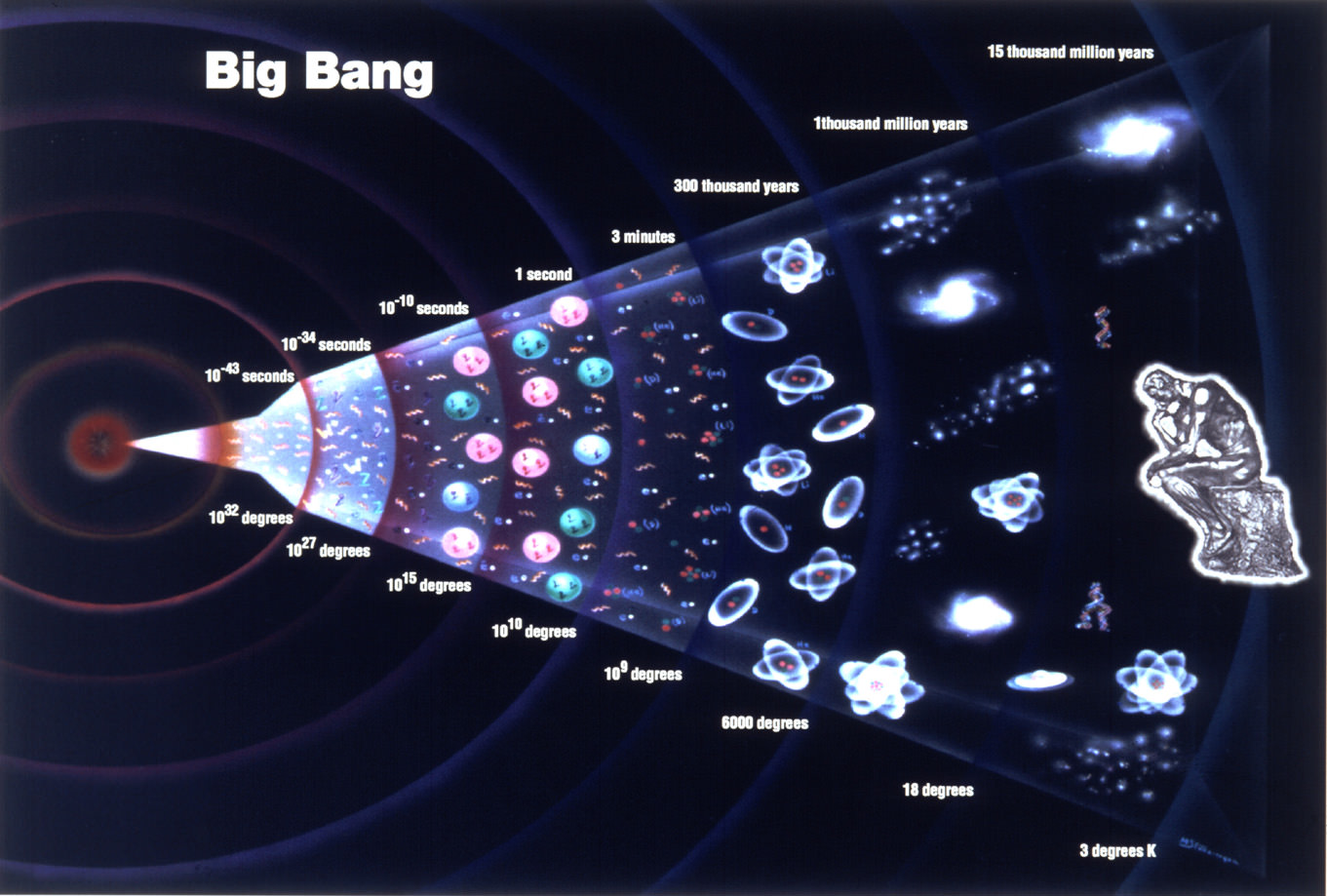

According to Nebular Theory, the Sun and all the planets of our Solar System began as a giant cloud of molecular gas and dust. Then, about 4.57 billion years ago, something happened that caused the cloud to collapse. This could have been the result of a passing star, or shock waves from a supernova, but the end result was a gravitational collapse at the center of the cloud.

From this collapse, pockets of dust and gas began to collect into denser regions. As the denser regions pulled in more and more matter, conservation of momentum caused it to begin rotating, while increasing pressure caused it to heat up. Most of the material ended up in a ball at the center while the rest of the matter flattened out into disk that circled around it.

The ball at the center would eventually form the Sun, while the disk of material would form the planets. The Sun spent about 100,000 years as a collapsing protostar before temperature and pressures in the interior ignited fusion at its core. The Sun started as a T Tauri star – a wildly active star that blasted out an intense solar wind. And just a few million years later, it settled down into its current form. The life cycle of the Sun had begun.

The Main Sequence:

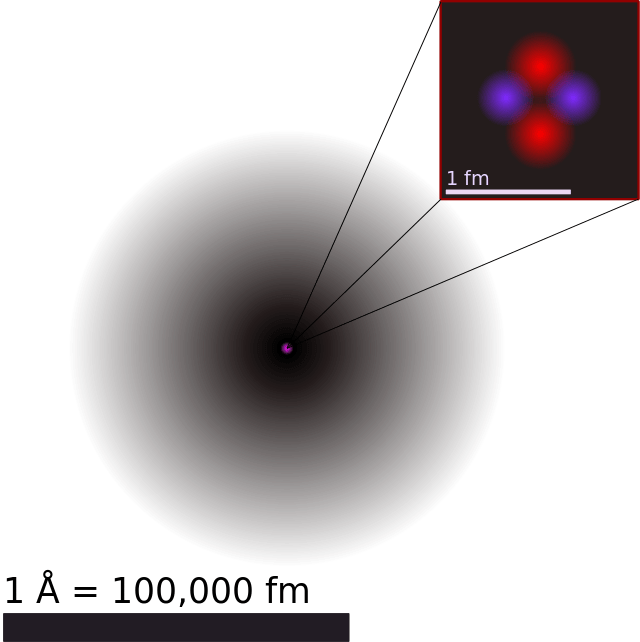

The Sun, like most stars in the Universe, is on the main sequence stage of its life, during which nuclear fusion reactions in its core fuse hydrogen into helium. Every second, 600 million tons of matter are converted into neutrinos, solar radiation, and roughly 4 x 1027 Watts of energy. For the Sun, this process began 4.57 billion years ago, and it has been generating energy this way every since.

However, this process cannot last forever since there is a finite amount of hydrogen in the core of the Sun. So far, the Sun has converted an estimated 100 times the mass of the Earth into helium and solar energy. As more hydrogen is converted into helium, the core continues to shrink, allowing the outer layers of the Sun to move closer to the center and experience a stronger gravitational force.

This places more pressure on the core, which is resisted by a resulting increase in the rate at which fusion occurs. Basically, this means that as the Sun continues to expend hydrogen in its core, the fusion process speeds up and the output of the Sun increases. At present, this is leading to a 1% increase in luminosity every 100 million years, and a 30% increase over the course of the last 4.5 billion years.

In 1.1 billion years from now, the Sun will be 10% brighter than it is today, and this increase in luminosity will also mean an increase in heat energy, which Earth’s atmosphere will absorb. This will trigger a moist greenhouse effect here on Earth that is similar to the runaway warming that turned Venus into the hellish environment we see there today.

In 3.5 billion years from now, the Sun will be 40% brighter than it is right now. This increase will cause the oceans to boil, the ice caps to permanently melt, and all water vapor in the atmosphere to be lost to space. Under these conditions, life as we know it will be unable to survive anywhere on the surface. In short, planet Earth will come to be another hot, dry Venus.

Core Hydrogen Exhaustion:

All things must end. That is true for us, that is true for the Earth, and that is true for the Sun. It’s not going to happen anytime soon, but one day in the distant future, the Sun will run out of hydrogen fuel and slowly slouch towards death. This will begin in approximate 5.4 billion years, at which point the Sun will exit the main sequence of its lifespan.

With its hydrogen exhausted in the core, the inert helium ash that has built up there will become unstable and collapse under its own weight. This will cause the core to heat up and get denser, causing the Sun to grow in size and enter the Red Giant phase of its evolution. It is calculated that the expanding Sun will grow large enough to encompass the orbit’s of Mercury, Venus, and maybe even Earth. Even if the Earth survives, the intense heat from the red sun will scorch our planet and make it completely impossible for life to survive.

Final Phase and Death:

Once it reaches the Red-Giant-Branch (RGB) phase, the Sun will haves approximately 120 million years of active life left. But much will happen in this amount of time. First, the core (full of degenerate helium), will ignite violently in a helium flash – where approximately 6% of the core and 40% of the Sun’s mass will be converted into carbon within a matter of minutes.

The Sun will then shrink to around 10 times its current size and 50 times its luminosity, with a temperature a little lower than today. For the next 100 million years, it will continue to burn helium in its core until it is exhausted. By this point, it will be in its Asymptotic-Giant-Branch (AGB) phase, where it will expand again (much faster this time) and become more luminous.

Over the course of the next 20 million years, the Sun will then become unstable and begin losing mass through a series of thermal pulses. These will occur every 100,000 years or so, becoming larger each time and increasing the Sun’s luminosity to 5,000 times its current brightness and its radius to over 1 AU.

At this point, the Sun’s expansion will either encompass the Earth, or leave it entirely inhospitable to life. Planets in the Outer Solar System are likely to change dramatically, as more energy is absorbed from the Sun, causing their water ices to sublimate – perhaps forming dense atmosphere and surface oceans. After 500,000 years or so, only half of the Sun’s current mass will remain and its outer envelope will begin to form a planetary nebula.

The post-AGB evolution will be even faster, as the ejected mass becomes ionized to form a planetary nebula and the exposed core reaches 30,000 K. The final, naked core temperature will be over 100,000 K, after which the remnant will cool towards a white dwarf. The planetary nebula will disperse in about 10,000 years, but the white dwarf will survive for trillions of years before fading to black.

Ultimate Fate of our Sun:

When people think of stars dying, what typically comes to mind are massive supernovas and the creation of black holes. However, this will not be the case with our Sun, due to the simple fact that it is not nearly massive enough. While it might seem huge to us, but the Sun is a relatively low mass star compared to some of the enormous high mass stars out there in the Universe.

As such, when our Sun runs out of hydrogen fuel, it will expand to become a red giant, puff off its outer layers, and then settle down as a compact white dwarf star, then slowly cooling down for trillions of years. If, however, the Sun had about 10 times its current mass, the final phase of its lifespan would be significantly more (ahem) explosive.

When this super-massive Sun ran out of hydrogen fuel in its core, it would switch over to converting atoms of helium, and then atoms of carbon (just like our own). This process would continue, with the Sun consuming heavier and heavier fuel in concentric layers. Each layer would take less time than the last, all the way up to nickel – which could take just a day to burn through.

Then, iron would starts to build up in the core of the star. Since iron doesn’t give off any energy when it undergoes nuclear fusion, the star would have no more outward pressure in its core to prevent it from collapsing inward. When about 1.38 times the mass of the Sun is iron collected at the core, it would catastrophically implode, releasing an enormous amount of energy.

Within eight minutes, the amount of time it takes for light to travel from the Sun to Earth, an incomprehensible amount of energy would sweep past the Earth and destroy everything in the Solar System. The energy released from this might be enough to briefly outshine the galaxy, and a new nebula (like the Crab Nebula) would be visible from nearby star systems, expanding outward for thousands of years.

All that would remain of the Sun would be a rapidly spinning neutron star, or maybe even a stellar black hole. But of course, this is not to be our Sun’s fate. Given its mass, it will eventually collapse into a white star until it burns itself out. And of course, this won’t be happening for another 6 billion years or so. By that point, humanity will either be long dead or have moved on. In the meantime, we have plenty of days of sunshine to look forward to!

We have written many interesting articles on the Sun here at Universe Today. Here’s What Color Is The Sun?, What Kind of Star is the Sun?, How Does The Sun Produce Energy?, and Could We Terraform the Sun?

Astronomy Cast also has some interesting episodes on the subject. Check them out- Episode 30: The Sun, Spots and All, Episode 108: The Life of the Sun, Episode 238: Solar Activity.

For more information, check out NASA’s Solar System Guide.