Ever since the invention of the telescope four hundred years ago, astronomers have been fascinated by the gas giant known as Jupiter. Between its constant, swirling clouds, its many, many moons, and its Giant Red Spot, there are many things about this planet that are both delightful and fascinating.

But perhaps the most impressive feature about Jupiter is its sheer size. In terms of mass, volume, and surface area, Jupiter is the biggest planet in our Solar System by a wide margin. And since people have been aware of its existence for thousands of years, it has played an active role in the cosmological systems many cultures. But just what makes Jupiter so massive, and what else do we know about it?

Size, Mass and Orbit:

Jupiter’s mass, volume, surface area and mean circumference are 1.8981 x 1027 kg, 1.43128 x 1015 km3, 6.1419 x 1010 km2, and 4.39264 x 105 km respectively. To put that in perspective, Jupiter diameter is roughly 11 times that of Earth, and 2.5 the mass of all the other planets in the Solar System combined.

But, being a gas giant, it has a relatively low density – 1.326 g/cm3 – which is less than one quarter of Earth’s. This means that while Jupiter’s volume is equivalent to about 1,321 Earths, it is only 318 times as massive. The low density is one way scientists are able to determine that it is made mostly of gases, though the debate still rages on what exists at its core (see below).

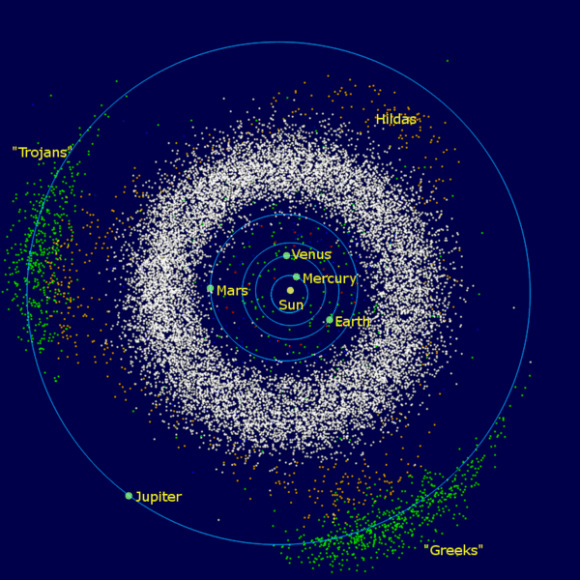

Jupiter orbits the Sun at an average distance (semi-major axis) of 778,299,000 km (5.2 AU), ranging from 740,550,000 km (4.95 AU) at perihelion and 816,040,000 km (5.455 AU) at aphelion. At this distance, Jupiter takes 11.8618 Earth years to complete a single orbit of the Sun. In other words, a single Jovian year lasts the equivalent of 4,332.59 Earth days.

However, Jupiter’s rotation is the fastest of all the Solar System’s planets, completing a rotation on its axis in slightly less than ten hours (9 hours, 55 minutes and 30 seconds to be exact. Therefore, a single Jovian year lasts 10,475.8 Jovian solar days. This orbital period is two-fifths that of Saturn, which means that the two largest planets in our Solar System form a 5:2 orbital resonance.

Structure and Composition:

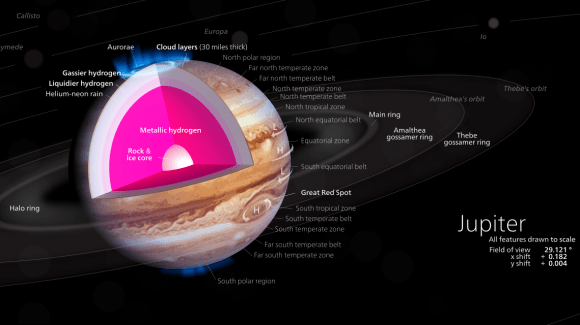

Jupiter is composed primarily of gaseous and liquid matter. It is the largest of the gas giants, and like them, is divided between a gaseous outer atmosphere and an interior that is made up of denser materials. It’s upper atmosphere is composed of about 88–92% hydrogen and 8–12% helium by percent volume of gas molecules, and approx. 75% hydrogen and 24% helium by mass, with the remaining one percent consisting of other elements.

The atmosphere contains trace amounts of methane, water vapor, ammonia, and silicon-based compounds as well as trace amounts of benzene and other hydrocarbons. There are also traces of carbon, ethane, hydrogen sulfide, neon, oxygen, phosphine, and sulfur. Crystals of frozen ammonia have also been observed in the outermost layer of the atmosphere.

The interior contains denser materials, such that the distribution is roughly 71% hydrogen, 24% helium and 5% other elements by mass. It is believed that Jupiter’s core is a dense mix of elements – a surrounding layer of liquid metallic hydrogen with some helium, and an outer layer predominantly of molecular hydrogen. The core has also been described as rocky, but this remains unknown as well.

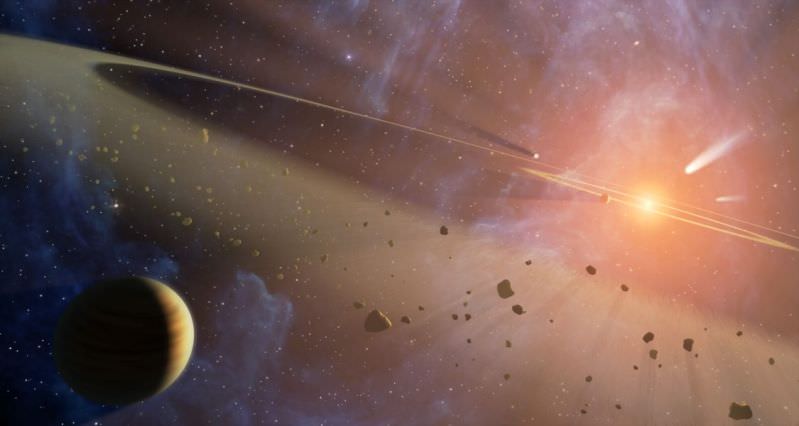

In 1997, the existence of the core was suggested by gravitational measurements, indicating a mass of from 12 to 45 times the Earth’s mass, or roughly 4%–14% of the total mass of Jupiter. The presence of a core is also supported by models of planetary formation that indicate how a rocky or icy core would have been necessary at some point in the planet’s history in order to collect all of its hydrogen and helium from the protosolar nebula.

However, it is possible that this core has since shrunk due to convection currents of hot, liquid, metallic hydrogen mixing with the molten core. This core may even be absent now, but a detailed analysis is needed before this can be confirmed. The Juno mission, which launched in August 2011 (see below), is expected to provide some insight into these questions, and thereby make progress on the problem of the core.

The temperature and pressure inside Jupiter increase steadily toward the core. At the “surface”, the pressure and temperature are believed to be 10 bars and 340 K (67 °C, 152 °F). At the “phase transition” region, where hydrogen becomes metallic, it is believed the temperature is 10,000 K (9,700 °C; 17,500 °F) and the pressure is 200 GPa. The temperature at the core boundary is estimated to be 36,000 K (35,700 °C; 64,300 °F) and the interior pressure at roughly 3,000–4,500 GPa.

Jupiter’s Moons:

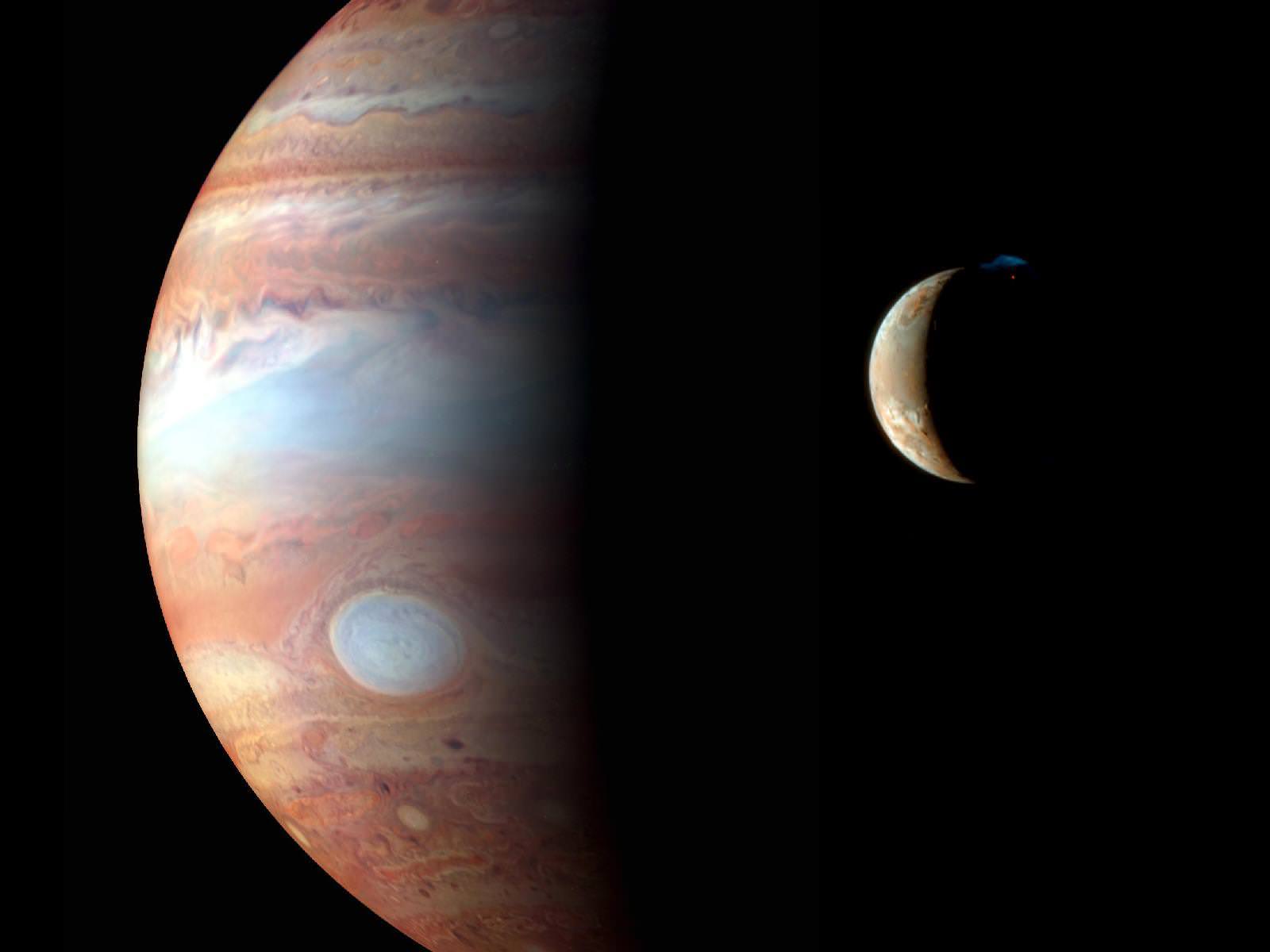

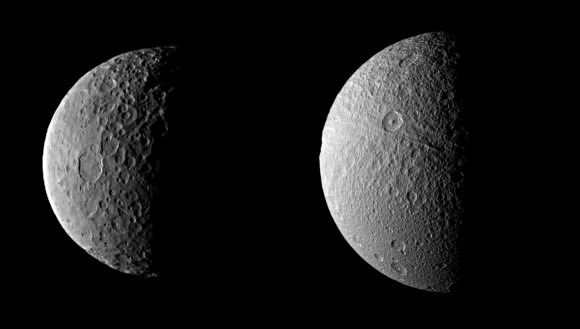

The Jovian system currently includes 67 known moons. The four largest are known as the Galilean Moons, which are named after their discoverer, Galileo Galilei. They include: Io, the most volcanically active body in our Solar System; Europa, which is suspected of having a massive subsurface ocean; Ganymede, the largest moon in our Solar System; and Callisto, which is also thought to have a subsurface ocean and features some of the oldest surface material in the Solar System.

Then there’s the Inner Group (or Amalthea group), which is made up of four small moons that have diameters of less than 200 km, orbit at radii less than 200,000 km, and have orbital inclinations of less than half a degree. This groups includes the moons of Metis, Adrastea, Amalthea, and Thebe. Along with a number of as-yet-unseen inner moonlets, these moons replenish and maintain Jupiter’s faint ring system.

Jupiter also has an array of Irregular Satellites, which are substantially smaller and have more distant and eccentric orbits than the others. These moons are broken down into families that have similarities in orbit and composition, and are believed to be largely the result of collisions from large objects that were captured by Jupiter’s gravity.

Atmosphere and Storms:

Much like Earth, Jupiter experiences auroras near its northern and southern poles. But on Jupiter, the auroral activity is much more intense and rarely ever stops. The intense radiation, Jupiter’s magnetic field, and the abundance of material from Io’s volcanoes that react with Jupiter’s ionosphere create a light show that is truly spectacular.

Jupiter also experiences violent weather patterns. Wind speeds of 100 m/s (360 km/h) are common in zonal jets, and can reach as high as 620 kph (385 mph). Storms form within hours and can become thousands of km in diameter overnight. One storm, the Great Red Spot, has been raging since at least the late 1600s. The storm has been shrinking and expanding throughout its history; but in 2012, it was suggested that the Giant Red Spot might eventually disappear.

Jupiter is perpetually covered with clouds composed of ammonia crystals and possibly ammonium hydrosulfide. These clouds are located in the tropopause and are arranged into bands of different latitudes, known as “tropical regions”. The cloud layer is only about 50 km (31 mi) deep, and consists of at least two decks of clouds: a thick lower deck and a thin clearer region.

There may also be a thin layer of water clouds underlying the ammonia layer, as evidenced by flashes of lightning detected in the atmosphere of Jupiter, which would be caused by the water’s polarity creating the charge separation needed for lightning. Observations of these electrical discharges indicate that they can be up to a thousand times as powerful as those observed here on the Earth.

Historical Observations of the Planet:

As a planet that can be observed with the naked eye, humans have known about the existence of Jupiter for thousands of years. It has therefore played a vital role in the mythological and astrological systems of many cultures. The first recorded mentions of it date back to the Babylon Empire of the 7th and 8th centuries BCE.

In the 2nd century, the Greco-Egyptian astronomer Ptolemy constructed his famous geocentric planetary model that contained deferents and epicycles to explain the orbit of Jupiter relative to the Earth (i.e. retrograde motion). In his work, the Almagest, he ascribed an orbital period of 4332.38 days to Jupiter (11.86 years).

In 499, Aryabhata – a mathematician-astronomer from the classical age of India – also used a geocentric model to estimate Jupiter’s period as 4332.2722 days, or 11.86 years. It has also been ventured that the Chinese astronomer Gan De discovered Jupiter’s moons in 362 BCE without the use of instruments. If true, it would mean that Galileo was not the first to discovery the Jovian moons two millennia later.

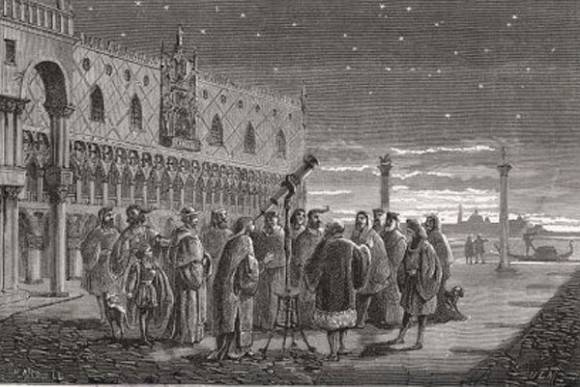

In 1610, Galileo Galilei was the first astronomer to use a telescope to observe the planets. In the course of his examinations of the outer Solar System, he discovered the four largest moons of Jupiter (now known as the Galilean Moons). The discovery of moons other than Earth’s was a major point in favor of Copernicus’ heliocentric theory of the motions of the planets.

During the 1660s, Cassini used a new telescope to discover Jupiter’s spots and colorful bands and observed that the planet appeared to be an oblate spheroid. By 1690, he was also able to estimate the rotation period of the planet and noticed that the atmosphere undergoes differential rotation. In 1831, German astronomer Heinrich Schwabe produced the earliest known drawing to show details of the Great Red Spot.

In 1892, E. E. Barnard observed a fifth satellite of Jupiter using the refractor telescope at the Lick Observatory in California. This relatively small object was later named Amalthea, and would be the last planetary moon to be discovered directly by visual observation.

In 1932, Rupert Wildt identified absorption bands of ammonia and methane in the spectra of Jupiter; and by 1938, three long-lived anticyclonic features termed “white ovals” were observed. For several decades, they remained as separate features in the atmosphere, sometimes approaching each other but never merging. Finally, two of the ovals merged in 1998, then absorbed the third in 2000, becoming Oval BA.

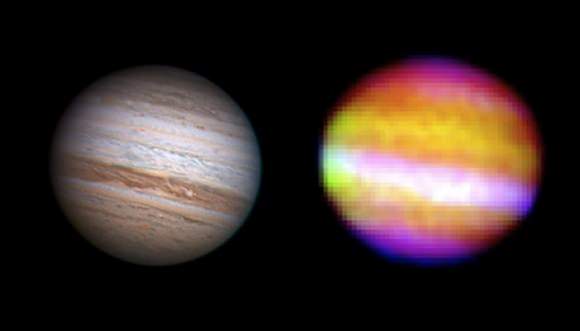

Beginning in the 1950s, radiotelescopic research of Jupiter began. This was due to astronomers Bernard Burke and Kenneth Franklin’s detection of radio signals coming from Jupiter in 1955. These bursts of radio waves, which corresponded to the rotation of the planet, allowed Burke and Franklin to refine estimates of the planet’s rotation rate.

Over time, scientists discovered that there were three forms of radio signals transmitted from Jupiter – decametric radio bursts, decimetric radio emissions, and thermal radiation. Decametric bursts vary with the rotation of Jupiter, and are influenced by the interaction of Io with Jupiter’s magnetic field.

Decimetric radio emissions – which originate from a torus-shaped belt around Jupiter’s equator – are caused by cyclotronic radiation from electrons that are accelerated in Jupiter’s magnetic field. Meanwhile, thermal radiation is produced by heat in the atmosphere of Jupiter. Visualizations of Jupiter using radiotelescopes have allowed astronomers to learn much about its atmosphere, thermal properties and behavior.

Exploration:

Since 1973, a number of automated spacecraft have been sent to the Jovian system and performed planetary flybys that brought them within range of the planet. The most notable of these was Pioneer 10, the first spacecraft to get close enough to send back photographs of Jupiter and its moons. Between this mission and Pioneer 11, astronomers learned a great deal about the properties and phenomena of this gas giant.

For example, they discovered that the radiation fields near the planet were much stronger than expected. The trajectories of these spacecraft were also used to refine the mass estimates of the Jovian system, and radio occultations by the planet resulted in better measurements of Jupiter’s diameter and the amount of polar flattening.

Six years later, the Voyager missions began, which vastly improved the understanding of the Galilean moons and discovered Jupiter’s rings. They also confirmed that the Great Red Spot was anticyclonic, that its hue had changed sine the Pioneer missions – turning from orange to dark brown – and spotted lightning on its dark side. Observations were also made of Io, which showed a torus of ionized atoms along its orbital path and volcanoes on its surface.

On December 7th, 1995, the Galileo orbiter became the first probe to establish orbit around Jupiter, where it would remain for seven years. During its mission, it conducted multiple flybys of all the Galilean moons and Amalthea and deployed an probe into the atmosphere. It was also in the perfect position to witness the impact of Comet Shoemaker–Levy 9 as it approached Jupiter in 1994.

On September 21st, 2003, Galileo was deliberately steered into the planet and crashed in its atmosphere at a speed of 50 km/s, mainly to avoid crashing and causing any possible contamination to Europa – a moon which is believed to harbor life.

Data gathered by both the probe and orbiter revealed that hydrogen composes up to 90% of Jupiter’s atmosphere. The temperatures data recorded was more than 300 °C (570 °F) and the wind speed measured more than 644 kmph (400 mph) before the probe vaporized.

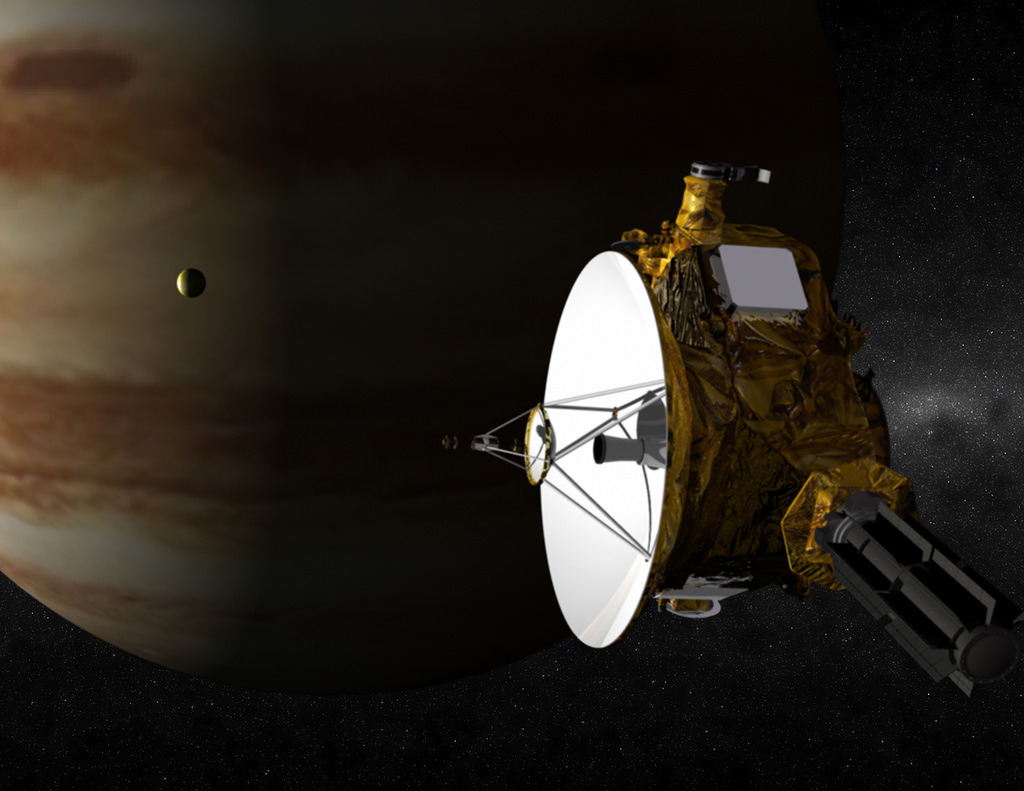

In 2000, the Cassini probe (while en route to Saturn) flew by Jupiter and provided some of the highest-resolution images ever taken of the planet. While en route to Pluto, the New Horizons space probe flew by Jupiter and measured the plasma output from Io’s volcanoes, studied all four Galileo moons in detail, and also conducting long-distance observations of Himalia and Elara.

NASA’s Juno mission, which launched in August 2011, achieved orbit around the Jovian planet on July 4th, 2016. The purpose of this mission to study Jupiter’s interior, its atmosphere, its magnetosphere and gravitational field, ultimately for the purpose of determining the history of the planet’s formation (which will shed light on the formation of the Solar System).

As the probe entered its polar elliptical orbit on July 4th after completing a 35-minute-long firing of the main engine, known as Jupiter Orbital Insertion (or JOI). As the probe approached Jupiter from above its north pole, it was afforded a view of the Jovian system, which it took a final picture of before commencing JOI.

On July 10th, the Juno probe transmitted its first imagery from orbit after powering back up its suite of scientific instruments. The images were taken when the spacecraft was 4.3 million km (2.7 million mi) from Jupiter and on the outbound leg of its initial 53.5-day capture orbit. The color image shows atmospheric features on Jupiter, including the famous Great Red Spot, and three of the massive planet’s four largest moons – Io, Europa and Ganymede, from left to right in the image.

The next planned mission to the Jovian system will be performed by the European Space Agency’s Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer (JUICE), due to launch in 2022, followed by NASA’s Europa Clipper mission in 2025.

Exoplanets:

The discovery of exoplanets has revealed that planets can get even bigger than Jupiter. In fact, the number of “Super Jupiters” observed by the Kepler space probe (as well as ground-based telescopes) in the past few years has been staggering. In fact, as of 2015, more than 300 such planets have been identified.

Notable examples include PSR B1620-26 b (Methuselah), which was the first super-Jupiter to be observed (in 2003). At 12.7 billion years of age, it is also the third oldest known planet in the universe. There’s also HD 80606 b (Niobe), which has the most eccentric orbit of any known planet, and 2M1207b (Lerna), which orbits the brown dwarf Fomalhaut b (Illion).

Here’s an interesting fact. Scientist theorize that a gas gain could get 15 times the size of Jupiter before it began deuterium fusion, making it a brown dwarf star. Good thing too, since the last thing the Solar System needs is for Jupiter to go nova!

Jupiter was appropriately named by the ancient Romans, who chose to name after the king of the Gods (also known as Jove). The more we have come to know and understand about this most-massive of Solar planets, the more deserving of this name it appears.

We have many interesting articles on Jupiter here at Universe Today. Here are some articles on the color and gravity of Jupiter, how it got its name, and how it shaped our Solar System.

Got questions about Jupiter’s greater mysteries? Then here’s Does Jupiter Have a Solid Core?, Could Jupiter Become a Star?, Could We Live on Jupiter?, and Could We Terraform Jupiter?

We have recorded a whole series of podcasts about the Solar System at Astronomy Cast.