[/caption]

A frequent plot device in the old “Mission: Impossible” television show was the special masks the IMF team used so they could impersonate anyone. Viewers were often surprised to find out who ended up being an imposter. Similarly, astronomers and planetary scientists are considering that a fair amount of Near Earth Objects (NEOs) aren’t what they appear: they could be comets impersonating asteroids. Paul Abell, from the Planetary Science Institute says between five and ten percent of NEOs could be comets that are being mistaken for asteroids, and Abell is working on ways to make unmasking them a mission that’s possible.

Some NEOs could be dying comets, those that have lost most of the volatile materials that create their characteristic tails. Others could be dormant and might again display comet-like features after colliding with another object, said Abell. He is using NASA’s Infrared Telescope Facility at the Mauna Kea Observatories in Hawaii and the MMT telescope on Mount Hopkins, south of Tucson, Ariz., to uncover observational signatures that separate extinct/dormant comets from near-Earth asteroids.

This is important for a couple of reasons. First, dormant comets in near-Earth space could become supply depots to support future exploration activities with water and other materials. Second, like other NEOs, they could pose a threat to Earth if they are on a collision course with our planet. Third, they can provide data on the composition and early evolution of the solar system because they are thought to contain unmodified remnants of the primordial materials that formed the solar system.

Unlike rocky asteroids that blast out craters when they slam into Earth, comets are structurally weak and likely to break up as they enter the atmosphere, leading to a heat and shockwave blast that would be much more devastating than the impact from an asteroid of the same size.

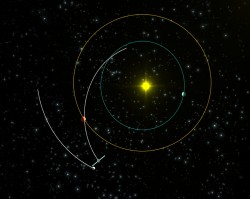

Low-activity, near-earth comets flashed onto the planetary-science radar screen in 2001, when NEO 2001 OG108 was discovered by the Lowell Observatory Near Earth Asteroid Search telescope. It had an orbit similar to comets coming in from the Oort Cloud, but had no cometary tail. But in early 2002 when it came closer to the sun, the heat vaporized some of the comet’s ice to create the clouds of dust and gas that make up the comet’s coma and tail. It was then reclassified as a comet.

“That’s what started me on this line of reasoning and scientific investigation,” Abell said.

By combining orbital data with spectra and the albedos (brightness) of these objects, Abell hopes to identify which are low-activity comets and where they are coming from.

“Are all these comets made of the same type of material or are they different?” Abell asked. “If they’re composed of different materials, they may have different spectral signatures, and our preliminary work on Jupiter-family comets and Halley-type comets shows that this may be true. Why is that? Is it something to do with the initial conditions of their formation regions? Or is it due to the different environments in which they spend most of their time?”

“All this is important to understanding their internal makeup, which will give us data on the material composition and evolution of the early solar system,” he added.

Source: PSI Press Release