[/caption]

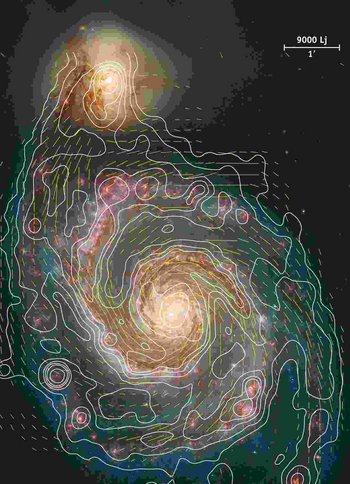

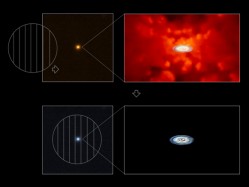

Although we can’t actually see a black hole, we can see the black hole’s effect on nearby matter. But even that is difficult because infrared light from clouds of dust and gas usually pollutes the view. But astronomers have found a way to get a clean view of the disks surrounding black holes by using a polarizing filter in the infrared. This technique works in particular when the region immediately surrounding the black hole emits a small amount of scattered light. Since scattered light is polarized, astronomers can use a filter that works like polarized sunglasses on large telescopes to detect this small amount of scattered light and measure it with unprecedented accuracy. Scientists have theorized these luminous disks existed around black holes, but until now have not been able to observe them.

The United Kingdom Infrared Telescope (UKIRT) on Mauna Kea in Hawaii has such an infrared filter, called a polarimeter (IRPOL). Astronmers have been using UKIRT and IRPOL and other telescopes for many years to search for proof that such a luminous supermassive black hole is accreting materials in a particular form of disk, where the disk shines directly using the gravitational binding energy of the black hole. Theorists have long thought that such disks should exist, and while there is a well-developed theory for it, until now theory and observations have been contradictory.

Dr. Makoto Kishimoto of the Max Planck Institute, principal investigator of this project, says: “After many years of controversy, we finally have very convincing evidence that the expected disk is truly there. However, this doesn’t answer all of our questions. While the theory has now been successfully tested in the outer region of the disk, we have to proceed to develop a better understanding of the regions of the disk closer to the black hole. But the outer disk region is important in itself – our method may provide answers to important questions for the outer boundary of the disk.”

Dr. Robert Antonucci of the University of California at Santa Barbara, a fellow investigator, says: “Our understanding of the physical processes in the disk is still rather poor, but now at least we are confident of the overall picture.”

Astronomers are hoping this new method will provide more information about the disks surrounding black holes in the near future.

Now, next on the agenda should be developing a suitable gravitational wave detector to confirm the existence of black holes!

Original News Source: University of Hawaii