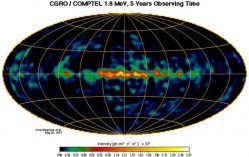

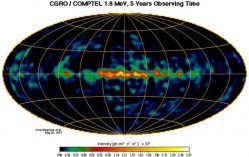

The life of NASA’s Compton Gamma Ray Observatory (CGRO) ended in 2000 when the spacecraft’s remains splashed down in the Pacific Ocean after a planned deorbit. But the space telescope’s spare parts live on, and they may have a new job. Instead of searching the universe for radioactive emissions, they could help military personnel search for dirty bombs and other radioactive materials. “If we can detect radioactive aluminum-26 on the other side of the galaxy we can find other radioactive materials like cesium-137 or cobalt-60 inside a building or on the other side of the street by the same method,” said Dr. James Ryan from the University of New Hampshire.

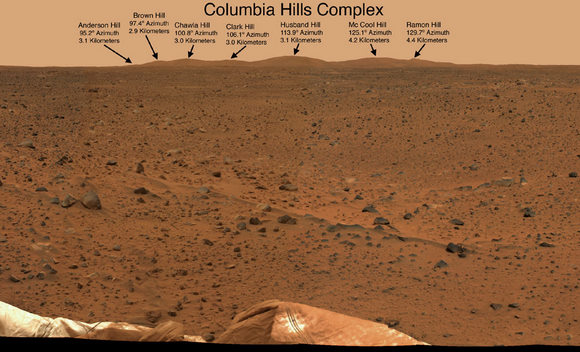

Ryan was a member of the research team that helped build and operate the gamma-ray imaging COMPTEL telescope onboard the CRGO, a 1991-2000 NASA mission. One of the key findings of COMPTEL was its map of radioactive aluminum from dying stars throughout the Galaxy.

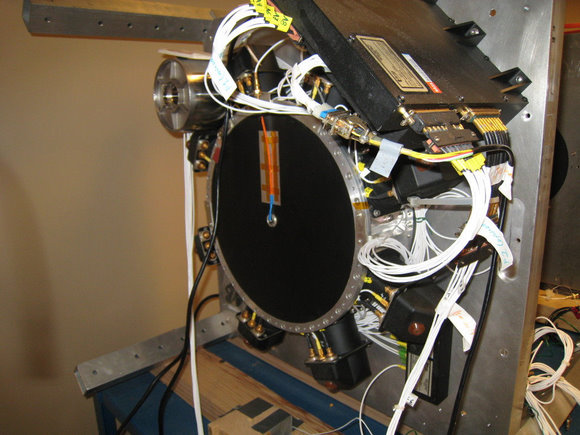

Identical flight spares of all the telescope components were built, just in case any of the parts failed. While the spares were never launched, they haven’t been collecting dust on a shelf. At different times, Ryan told Universe Today, the flight spares were assembled into a working telescope, sometimes as a student exercise and once for the benefit of the US Army as a test for probing the interior of buildings based on the background gamma radiation being emitted from the contents of the building.

“It is a sensitive instrument and it required no great thought to envision this use for it,” Ryan said of his idea to use the parts to pinpoint the location of dirty bombs. He was motivated by witnessing a National Guard drill to search for and clean up radioactive material left over by “terrorists.”

“It was clear that we would be able to sense the presence and approximate location of the radioactive material without entering the building with this device,” he said.

The device, known as GRETA, short for the Gamma-ray Experimental Telescope Assembly, could potentially be loaded on a truck and used for homeland security work such as scanning shipping containers or buildings for radioactive materials.

GRETA can accurately determine the direction from which a radioactive source is being emitted by creating an image, unlike current technology used by the military, such as Geiger counters or spectrometers that can only determine that radiation in is the vicinity.

“They might detect the presence of cesium-137 but they won’t know where it is unless they get right up close to it, they would have to fish around inside the building,” said Ryan, which would be a safety issue for military personnel.

Other media outlets report that some scientists doubt the applicability of this technology, saying GRETA’s “older” design has its limitations. But Ryan told Universe Today that current technology has changed very little from what COMPTEL, and GRETA, employ.

“Few, if any, scintillator detectors today will perform better than what is in GRETA,” he said. “There are newer designs for gamma-ray telescopes under development, but they are far from a deployable state. All are expensive, far more than a GRETA-type instrument. In fact, one could argue that GRETA is optimized for this application, because it provides the sensitivity necessary for the imaging and spectroscopy, while still remaining affordable and deployable on a short time scale.”

While GRETA is a prototype, the blueprints for the detectors, electronics and operation software still exist and can be used, with little modification, to build up a commercial unit for a real field test.

Ryan said there could be several potential “customers” or users for this device. “The National Guard is an obvious one, because they are charged with the clean up and disposal problem if, and when, a terrorist cell is uprooted. The US Border Patrol, various branches of the military and different port authorities could all find this useful,” Ryan said.

More information about CGRO.