Inflation theory proposes that the universe underwent a period of exponential expansion right after the Big Bang. One of the key predictions of inflation theory is the presence of a particular spectrum of “gravitational radiation”—ripples in the fabric of space-time that are really hard to detect but thought to exist. But a team of researchers has now found that gravitational radiation can be produced by a mechanism other than inflation. So this type of radiation, if eventually detected, won’t provide the conclusive evidence for inflation theory that was once was thought to be a certainty.

“If we see a primordial gravitational wave background, we can no longer say for sure it is due to inflation,” said noted astronomer Lawrence Krauss, from Case Western Reserve University.

Inflation theory first was proposed by cosmologist Alan Guth in 1981 as a means to explain some features of the universe that had previously baffled astronomers, such as why the universe is so close to being flat and why it is so uniform. Today, inflation remains the best way to theoretically understand many aspects of the early Big Bang universe, but most of the theory’s predictions are somewhat vague enough that even if the predictions were observed, they probably wouldn’t provide a clear-cut confirmation of the theory.

But gravitational radiation was considered one of the key predictions of inflation theory, and detection of this spectrum was regarded among physicists as “smoking gun” evidence that inflation did in fact occur, billions of years ago.

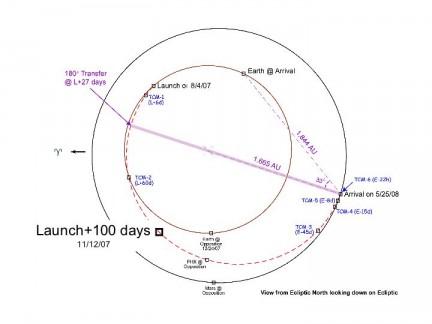

Gravitational radiation is a prediction of Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity. According to the theory, whenever large amounts of mass or energy are shifting around, it disrupts the surrounding space-time and ripples emanate from the region where the shift occurs. These ripples aren’t easily detected, but there is one experiment designed to look directly for this radiation, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory (LIGO) in Livingston, Louisiana. The upcoming Planck Mission, set to launch in 2009 will look for it indirectly by looking at the cosmic microwave background.

Until now it was widely believed that detecting gravitational radiation in the form of polarized light from the CMB would confirm inflation theory, since it was thought inflation would be the only way this radiation could be produced. But Krauss and his team have raised the issue of whether this radiation can be unmistakably tied to inflation.

Krauss’s team proposes that a phenomenon called “symmetry breaking,” can also produce gravitational radiation. Symmetry breaking is a central part of fundamental particle physics, where a system goes from being symmetrical to a low energy state that is not symmetrical. Krauss’s explanation is that a “scalar field” (similar to an electric or magnetic field) becomes aligned as the universe expands. But as the universe expands, each region over which the field is aligned comes into contact with other regions where the field has a different alignment. When that happens the field relaxes into a state where it is aligned over the entire region and in the process of relaxing it emits gravitational radiation.

This is all fairly confusing, but the sweetened condensed version is that if gravitational radiation is ever detected, that event won’t necessarily verify inflation theory. Therefore, whether inflation theory can ever be confirmed remains to be seen.

Krauss’s paper “Nearly Scale Invariant Spectrum of Gravitational Radiation from Global Phase Transitions” is published in the Aprill 2008 Physical Review Letters.

Original News Source: Case Western Reserve University press release