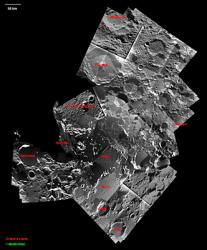

Amazingly, the two Mars rovers, Spirit and Opportunity, have been working diligently on the surface of the Red Planet for almost four years now. So far, Opportunity has grabbed most of the spotlight, finding evidence for past water on Mars within months after landing on the smooth plains of Meridiani Planum. While Spirit has been working just as hard, if not harder, climbing hills and traversing the rocky terrain of Gusev Crater, she hasn’t yet caused quite the stir that her twin has. But now, a recent discovery by Spirit at an area called Home Plate has researchers puzzling over a possible habitat for past microbial organisms.

What Spirit found is a patch of nearly pure silica, a main ingredient in window glass.

“This concentration of silica is probably the most significant discovery by Spirit for revealing a habitable niche that existed on Mars in the past,” said Steve Squyres, principal investigator for the rovers’ science payload.

The silica could have been produced from either a hot-spring type of environment or another type of environment called a fumarole, where acidic steam rises through cracks in the planet’s surface. On Earth, both of these types of environments teem with microbial life.

“The evidence is pointing most strongly toward fumarolic conditions, like you might see in Hawaii and in Iceland,” said Squyres. “Compared with deposits formed at hot springs, we know less about how well fumarolic deposits can preserve microbial fossils. That’s something needing more study here on Earth.”

Squyres said the patch that Spirit has been studying is more than 90 percent silica, and that there aren’t many ways to explain such a high concentration. One way is to selectively remove silica from the native volcanic rocks and concentrate it in the deposits Spirit found. Hot springs can do that, dissolving silica at high heat and then dropping it out of solution as the water cools. Another way is to selectively remove almost everything else and leave the silica behind. Acidic steam at fumaroles can do that. Scientists are still assessing both possible origins.

One reason Squyres favors the fumarole story is that the silica-rich soil on Mars has an enhanced level of titanium. On Earth, titanium levels are relatively high in some fumarolic deposits.

Meanwhile both rovers are hunkering down for another winter season on Mars. Spirit’s solar panels are currently coated with dust from the huge dust storm the rovers endured this summer, and Spirit will need to conserve energy in order to survive the low light levels during the winter.

“The last Martian winter, we didn’t move Spirit for about seven months,” said John Callas, project manager for the rovers. “This time, the rover is likely to be stationary longer and with significantly lower available energy each Martian day.”

I’m keeping my fingers crossed for another solar panel cleaning windstorm event, which has happened previously, giving the rovers a boost in power.

Original News Source: Jet Propulsion Laboratory News Release