What lies beneath Pluto’s icy heart? New research indicates there could be a salty “Dead Sea”-like ocean more than 100 kilometers thick.

“Thermal models of Pluto’s interior and tectonic evidence found on the surface suggest that an ocean may exist, but it’s not easy to infer its size or anything else about it,” said Brandon Johnson from Brown University. “We’ve been able to put some constraints on its thickness and get some clues about composition.”

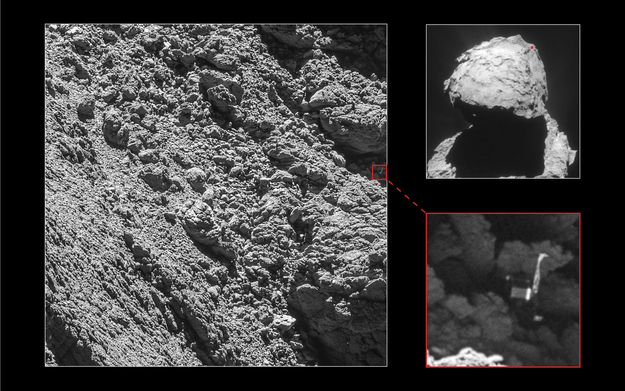

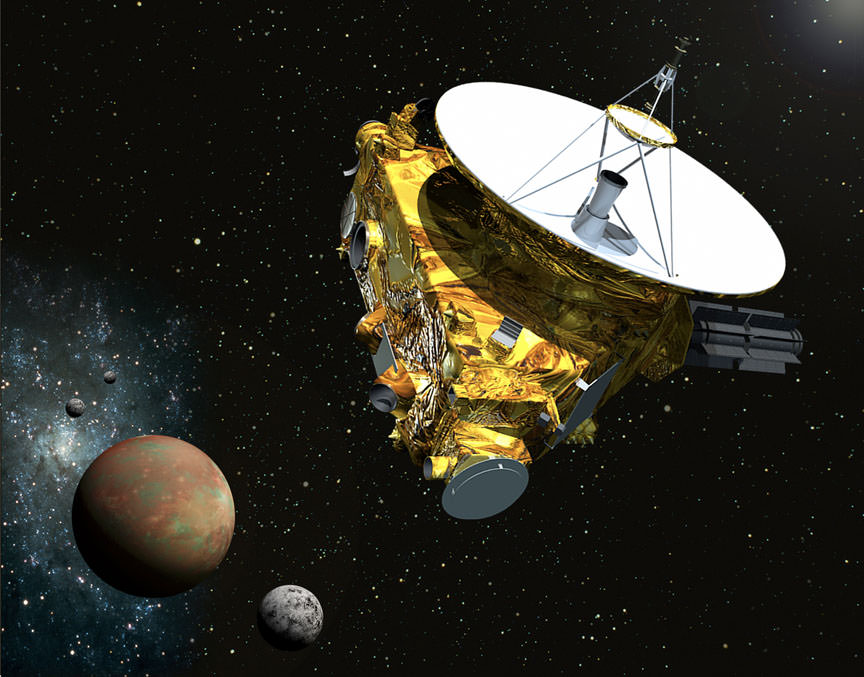

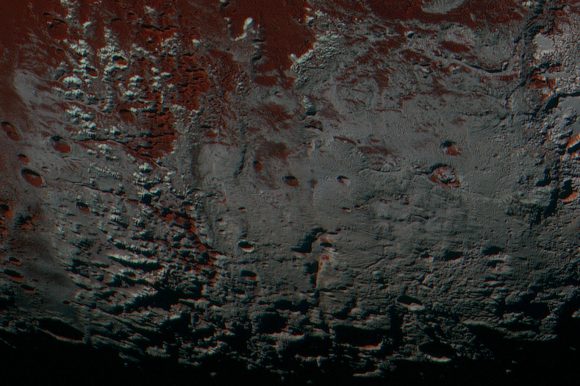

Research by Johnson and his team focused Pluto’s “heart” – a region informally called Sputnik Planum, which was photographed by the New Horizons spacecraft during its flyby of Pluto in July of 2015.

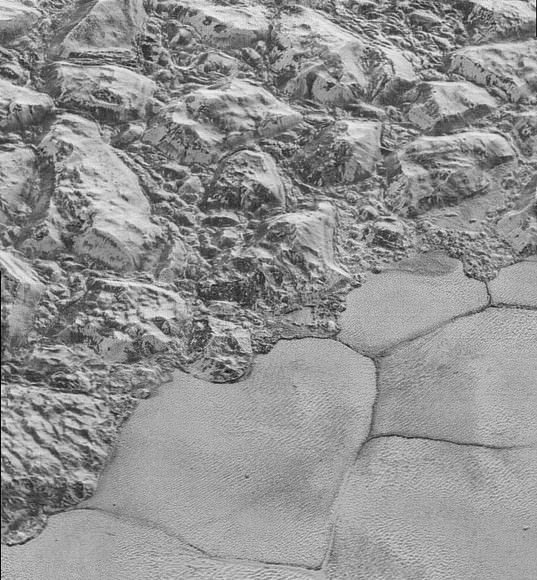

New Horizons’ Principal Investigator Alan Stern called Sputnik Planum “one of the most amazing geological discoveries in 50-plus years of planetary exploration,” and previous research showed the region appears to be constantly renewed by current-day ice convection.

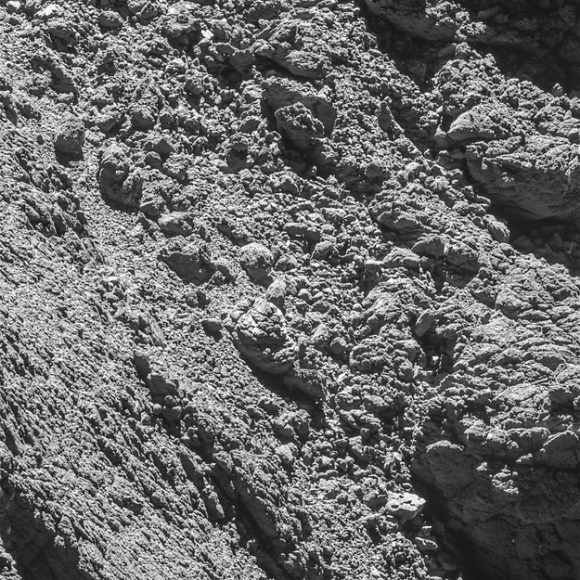

The heart is a 900 km wide basin — bigger than Texas and Oklahoma combined — and at least the western half of it appears to have been formed by an impact, likely by an object 200 kilometers across or larger.

Johnson and colleagues Timothy Bowling of the University of Chicago and Alexander Trowbridge and Andrew Freed from Purdue University modeled the impact dynamics that created a massive crater on Pluto’s surface and also looked at the dynamics between Pluto and its moon Charon.

The two are tidally locked with each other, meaning they always show each other the same face as they rotate. Sputnik Planum sits directly on the tidal axis linking the two worlds. That position suggests that the basin has what’s called a positive mass anomaly — it has more mass than average for Pluto’s icy crust. As Charon’s gravity pulls on Pluto, it would pull proportionally more on areas of higher mass, which would tilt the planet until Sputnik Planum became aligned with the tidal axis.

So instead of being a hole in the ground, the crater actually has been filled back in. Part of it has been filled in by the convecting nitrogen ice. While that ice layer adds some mass to the basin, it isn’t thick enough on its own to make Sputnik Planum have positive mass.

The rest of that mass, Johnson said, may be generated by a liquid lurking beneath the surface.

Johnson and his team explained it like this:

Like a bowling ball dropped on a trampoline, a large impact creates a dent on a planet’s surface, followed by a rebound. That rebound pulls material upward from deep in the planet’s interior. If that upwelled material is denser than what was blasted away by the impact, the crater ends up with the same mass as it had before the impact happened. This is a phenomenon geologists refer to as isostatic compensation.

Water is denser than ice. So if there were a layer of liquid water beneath Pluto’s ice shell, it may have welled up following the Sputnik Planum impact, evening out the crater’s mass. If the basin started out with neutral mass, then the nitrogen layer deposited later would be enough to create a positive mass anomaly.

“This scenario requires a liquid ocean,” Johnson said. “We wanted to run computer models of the impact to see if this is something that would actually happen. What we found is that the production of a positive mass anomaly is actually quite sensitive to how thick the ocean layer is. It’s also sensitive to how salty the ocean is, because the salt content affects the density of the water.”

The models simulated the impact of an object large enough to create a basin of Sputnik Planum’s size hitting Pluto at a speed expected for that part in the solar system. The simulation assumed various thicknesses of the water layer beneath the crust, from no water at all to a layer 200 kilometers thick.

The scenario that best reconstructed Sputnik Planum’s observed size depth, while also producing a crater with compensated mass, was one in which Pluto has an ocean layer more than 100 kilometers thick, with a salinity of around 30 percent.

“What this tells us is that if Sputnik Planum is indeed a positive mass anomaly —and it appears as though it is — this ocean layer of at least 100 kilometers has to be there,” Johnson said. “It’s pretty amazing to me that you have this body so far out in the solar system that still may have liquid water.”

Johnson he and other researchers will continue study the data sent back by New Horizons to get a clearer picture Pluto’s intriguing interior and possible ocean.

Further reading: Brown University, New Horions/APL