So, that ‘strong’ signal from aliens everyone was so excited about this week? Turns out, it was probably something from Earth, maybe a satellite passing overhead or another object of “terrestrial origin,” the Russian researchers have concluded.

Yeah. Dang.

“This supports our initial assumption that the signal was made by human intelligence, not extraterrestrial intelligence,” said Doug Vakoch, President of METI International (Messaging Extraterrestrial Intelligence), a group doing follow-up observations of the star system HD 164595, where the signal was thought to maybe, perhaps originate.

When the news broke of the possible alien signal, SETI scientists were quick to temper the excitement with measured skepticism, saying more often than not, these signals end up being “natural radio transients” (stellar flare, active galactic nucleus, microlensing of a background source, etc.) or interference of a terrestrial nature (a passing satellite or a microwave oven, for example.)

But still, people were excited and the news went viral. Crazy viral.

“Being no stranger to how the media can hype SETI stories, I can sympathize with those at the center of the latest dustup,” said astronomer and SETI researcher Jason Wright from Penn State University. “It’s understandable that many content outlets, seeking ‘clickbait’ headlines, would spin this particular story in the most intriguing, exciting way, and once that happens a ‘bidding war’ of hype can make the story spin out of control.”

But is it all about clickbait? Since I’m part of the media (and admittedly was initially very excited about this story,) I’d like to think that the excitement and viral-tendencies of news about possible alien signals say more about humanity’s fervent hope that we aren’t alone in the cosmos, rather than who can get the most pageviews.

And I do know that researchers who dedicate their careers to the search for alien signals and Earth-like planets aren’t doing so just so they can keep telling us to not get excited. They, too, are hoping for that chance, that very remote possibility, that we’ve got company in our big and magnificent Universe.

“You can’t always be cynical,” said SETI senior astronomer Seth Shostak. “If a signal is looking promising, we are going to check it out.”

And that’s the thing, say the researchers. They get signals like this all the time.

“This is the sort of thing SETI researchers do all the time, because by the nature of the search, radio SETI experiments come across strong signals all the time,” Vakoch said via email. “At the end of the day, these need to be confirmed as coming from distant locations in space, and if we can’t, we need to consider them spurious. The unusual feature of HD 164595 is that this process of checking is being followed by the media.”

And while scientists were surprised (and maybe annoyed) at the amount of attention the ‘alien signal’ news got this week, there is an upside.

“The silver living here is that those who read the more responsible stories carefully will learn a lot about how SETI works,” Wright told Universe Today, “that communication SETI researchers see “one-off” signals all the time from both astronomical and terrestrial sources, in addition to perhaps the occasional instrumental glitch. Searches using arrays (like the ATA) have an automatic check against many of these, but in any event no one will be popping the champaign until a signal repeats enough for an independent telescope and instrument to detect it, and its intelligent origin is clear.”

“The public is getting an inside view of the usual process of following up interesting SETI candidates,” said Vakoch. “This helps the public understand the standard process of doing SETI: we find interesting signals, and then we see if we can verify them. If not, we move on.”

Vakoch and Wright said that the confirmation process, however, involves a lot of steps, and it’s not always easy or quick to follow-up. So, most of the time, determining the source of the signal takes time.

“Unlike Hollywood movies, where you get a quick “yes or no” about a possible signal from aliens,” Vakoch explained, “the real SETI confirmation process takes some time. It’s easy to think that all we need to do is get on the phone with an astronomer at another location, and we’re all set. But even when colleagues at other facilities are willing to observe, they may face technical limitations.”

Typical radio SETI searches look for narrowband signals, and most observatories aren’t set up to detect such signals on short notice. And even though radio observatories can make observations even when it’s cloudy, there can be other types of local interference at certain radio frequencies.

“If you need to do a real-time follow-up of a promising SETI signal, you might face significant roadblocks to a ready confirmation – even if the signal is really there,” Vakoch said.

Another upside of the recent media attention is that SETI researchers can let everyone know they aren’t getting much funding for this type of research, and the search could really use a lot more eyes and ears on the Universe, as Jill Tartar tweeted:

Re: HD 164595 – who knows? One telescope is not enough and an array is better.

— Jill Tarter (@jilltarter) August 30, 2016

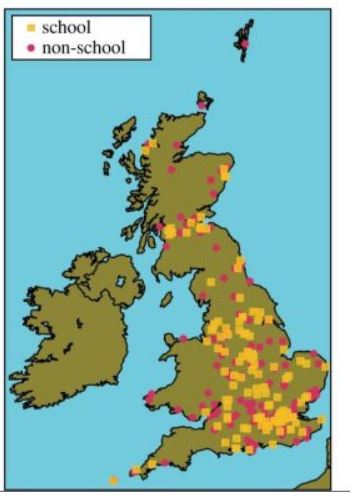

“It’s all the more evident that we need to replicate these innovative optical SETI systems over and over,”Vakoch said, “so we can have a global network of modest-sized observatories ready for follow-up of promising SETI signals. Developing such a network is one of METI International’s top priorities as an organization.”

(You can support SETI here and find out more about METI and optical SETI here.)

Wright said while the public interest in SETI is great, sometimes the media (or the tin foil hat crowd or conspiracy theorists) can blow things out of proportion.

“This can make it hard for anyone doing SETI to talk about their work, because any mention of ‘strange’ or ‘candidate’ signals has the potential to enter that echo chamber,” he said.

Which can go viral.

But if anyone is worried that SETI researchers are keeping secrets or not telling the whole story, I can personally vouch that during this week, absolutely every SETI researcher I contacted answered all my questions in an extremely timely manner (and provided even more information than I was expecting) plus, other researchers contacted me, asking to be able to explain the signal and the process of how SETI works.

“Nothing would make us more excited than to verify it,” said Bill Diamond, president and CEO of SETI, “But we have to observe it and look at the data.”

Further reading:

“Let’s Be Careful About This SETI Signal” by Franck Marchis

“No, we almost certainly did not detect an alien signal from a nearby star” by Phil Plait

SETI is Hopeful Yet Skeptical that Russians Found Aliens by Dean Takahashi

“That Alien Signal? Observations Are Coming Up Empty” by Nadia Drake