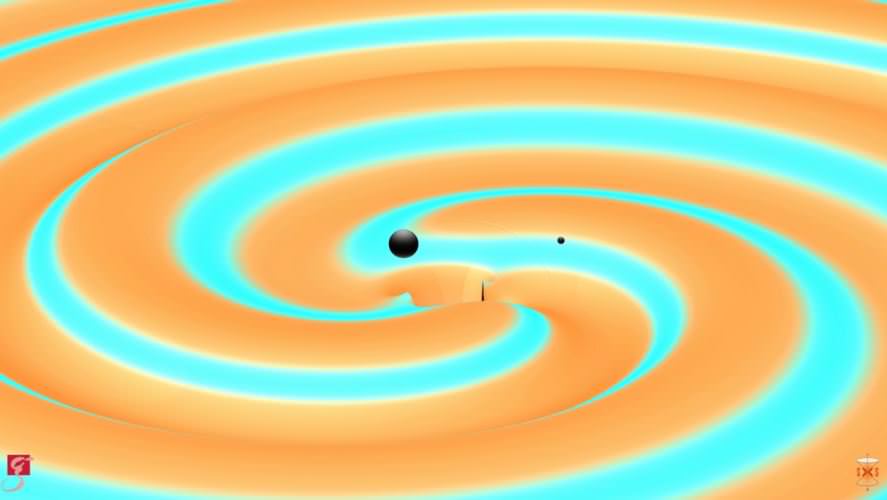

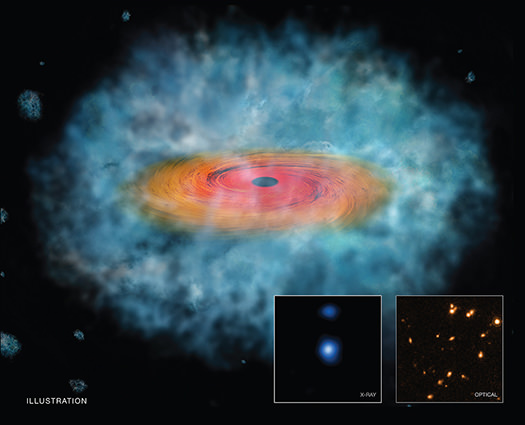

Astronomers have been finding some extremely old supermassive black holes, ones that formed when the Universe was quite young. But they were puzzled at how a black hole could grow to such tremendous size when the Universe itself was just a toddler.

Astronomers have now found a unique set of conditions were present half a billion years after the Big Bang that allowed these monster black holes to form. An unusual source of intense radiation created what are called “direct-collapse black holes.”

“It’s a cosmic miracle,” said Volker Bromm of The University of Texas at Austin, who worked with several astronomers on the finding. “It’s the only time in the history of the universe when conditions are just right for them to form.”

The conventional understanding of how black holes form is called the accretion theory, where an extremely massive star collapses and black hole “seeds” are built from the collapse by pulling in gas from their surroundings and by mergers of smaller black holes. But that process takes a long time, much longer than the time these quickly forming black holes were around. Plus, the early universe didn’t have the quantities of gas and dust needed for supermassive black holes to grow to their gigantic size.

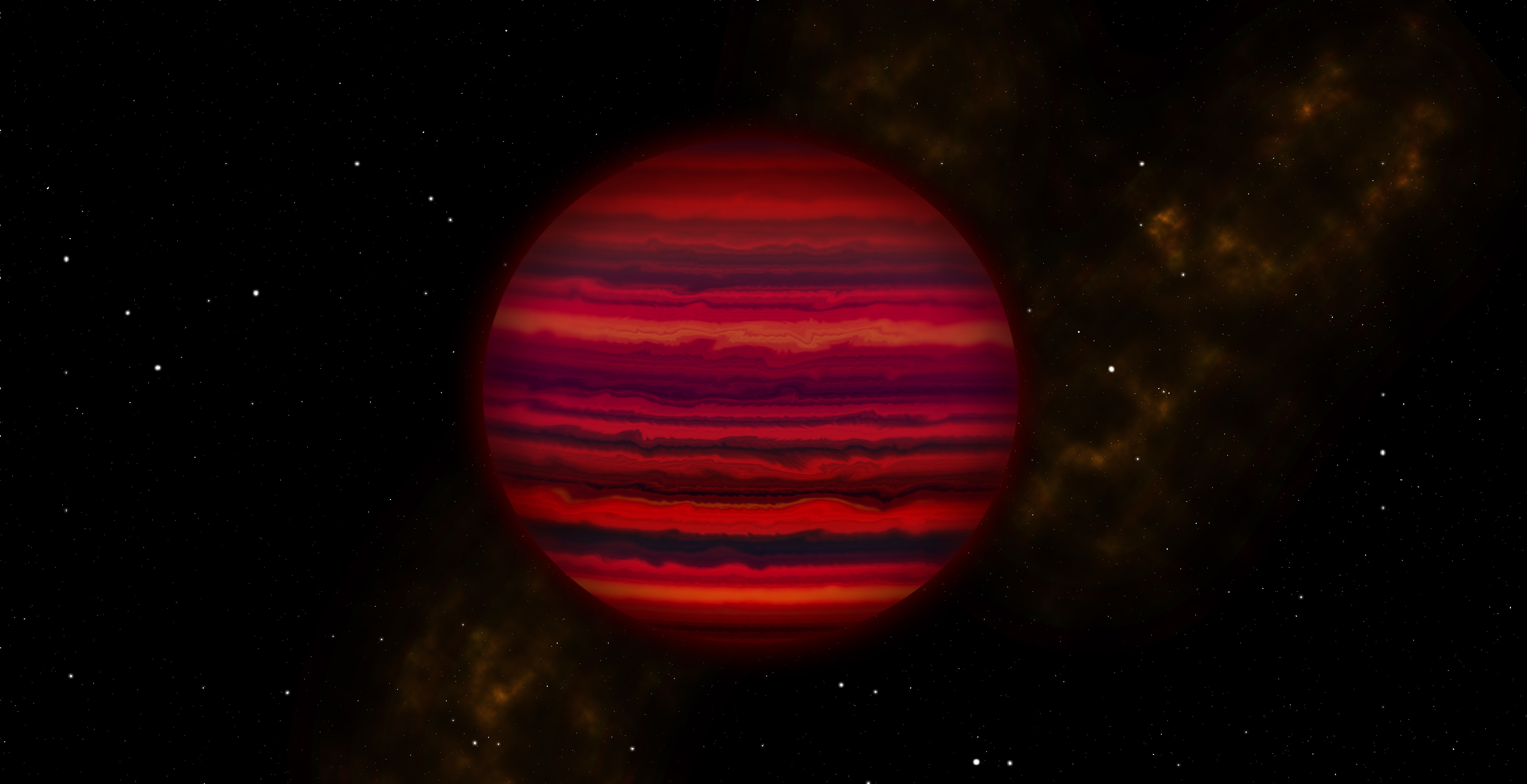

The new findings suggest instead that some of the first black holes formed directly when a cloud of gas collapsed, bypassing any other intermediate phases, such as the formation and subsequent destruction of a massive star.

Of course, like any black hole, these “direct collapse” black holes can’t be seen. But there was strong evidence for their existence, as they are needed to power the highly luminous quasars detected in the young universe. A quasar’s great brightness comes from matter spiraling into a supermassive black hole, heating to millions of degrees, creating jets that shine like beacons across the Universe. But since the accretion theory doesn’t explain supermassive black holes in extremely distant — and therefore young — universe, astronomers couldn’t explain the quasars either. This has been called “the quasar seed problem.”

“The quasars observed in the early universe resemble giant babies in a delivery room full of normal infants,” said Avi Loeb from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, who worked with Bromm. “One is left wondering: what is special about the environment that nurtured these giant babies? Typically the cold gas reservoir in nearby galaxies like the Milky Way is consumed mostly by star formation.”

But In 2003, Bromm and Loeb came up with a theoretical idea to get an early galaxy to form a supermassive seed black hole, by suppressing the otherwise prohibitive energy input from star formation. They called the process “direct collapse.”

“Begin with a “primordial cloud of hydrogen and helium, suffused in a sea of ultraviolet radiation,” Bromm said. “You crunch this cloud in the gravitational field of a dark-matter halo. Normally, the cloud would be able to cool, and fragment to form stars. However, the ultraviolet photons keep the gas hot, thus suppressing any star formation. These are the desired, near-miraculous conditions: collapse without fragmentation! As the gas gets more and more compact, eventually you have the conditions for a massive black hole.”

This set of cosmic conditions appears to have only existed in the very early universe, and this process does not happen in galaxies today.

To test their theory, Bromm, Loeb and their colleague Aaron Smith started studying a galaxy called CR7, identified by a Hubble Space Telescope survey called COSMOS as being around at less than 1 billion years after the Big Bang.

David Sobral of the University of Lisbon had made follow-up observations of CR7 with some of the world’s largest ground-based telescopes, including Keck and the VLT. These uncovered some extremely unusual features in the light signature coming from CR7. Specifically, the Lyman-alpha hydrogen line was several times brighter than expected. Remarkably, the spectrum also showed an unusually bright helium line.

“Whatever is driving this source is very hot — hot enough to ionize helium,” Smith said, about 100,000 degrees Celsius.

These and other unusual features in the spectrum meant that it could either be a cluster of primordial stars or a supermassive black hole likely formed by direct collapse.

Smith ran simulations for both scenarios and while the star cluster scenario “spectacularly failed,” Smith said, the direct collapse black hole model performed well.

Also, earlier this year, researchers using combined data from the Chandra X-ray Observatory, Hubble Space Telescope, and Spitzer Space Telescope to identify these possible black hole seeds. They found two objects, both of these matched the theoretical profile in the infrared data. (read their paper here.)

It seems astronomers are “converging on this model,” Smith said, for solving the quasar seed problem and the early black hole conundrum.

Stay tuned.

Bromm, Loeb and Smith’s work is published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Sources:

RAS, Harvard-Smithsonian CfA, Press release for NASA’s detection of direct collapse black holes earlier this year.