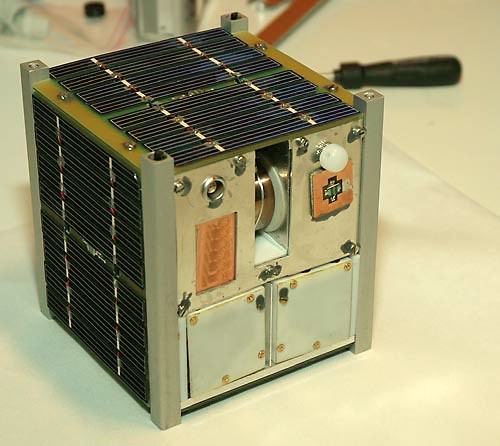

Here’s the 22nd-century version of breaking the surly bonds of Earth: NASA and private company Made In Space have just collaborated on the first 3-D printed part in space, ever.

The milestone yesterday (Nov. 25) is a baby step towards off-Earth manufacturing, but the implications are huge. If these testbeds prove effective enough, eventually we can think of creating these parts in other destinations such as the Moon, or an asteroid, or even Mars.

“We look at the operation of the 3-D printer as a transformative moment, not just for space development, but for the capability of our species to live away from Earth,” stated Aaron Kemmer, CEO of Made In Space — the company that developed the printer.

There are still kinks to be worked out, however. The “part adhesion” on the tray after the piece was created had a bond that was mightier than controllers anticipated, which could mean that bonding is different in microgravity. A second calibration coupon should be created shortly as controllers make adjustments to the process.

We’ll see several of these “test coupons” manufactured in the next few months and then sent back to Earth for more detailed analysis. Meanwhile, we have two more 3-D printers to look forward to in space: one created by the Italians that should arrive while their citizen, Samantha Cristoforetti, is still on station (she just arrived a few days ago) and a second one created by Made In Space that is supposed to commercialize the process.

The idea of 3-D printing has been discussed extensively in the media by both NASA and the European Space Agency in the past year or so. ESA has released media speculating on how additive manufacturing could be used to create Moon bases at some distant date. Meanwhile, NASA has talked about perhaps creating food using a 3-D printer.

If additive manufacturing takes off, so to speak, it could reduce shipping costs from Earth to the International Space Station because controllers could just send up a set of instructions to replace a part or tool. But NASA should move quickly to test this stuff out, according to a recent National Research Council report; the station is approved for operations only until 2020 (so far), which leaves only about five years or so to do testing before agencies possibly move to other destinations.