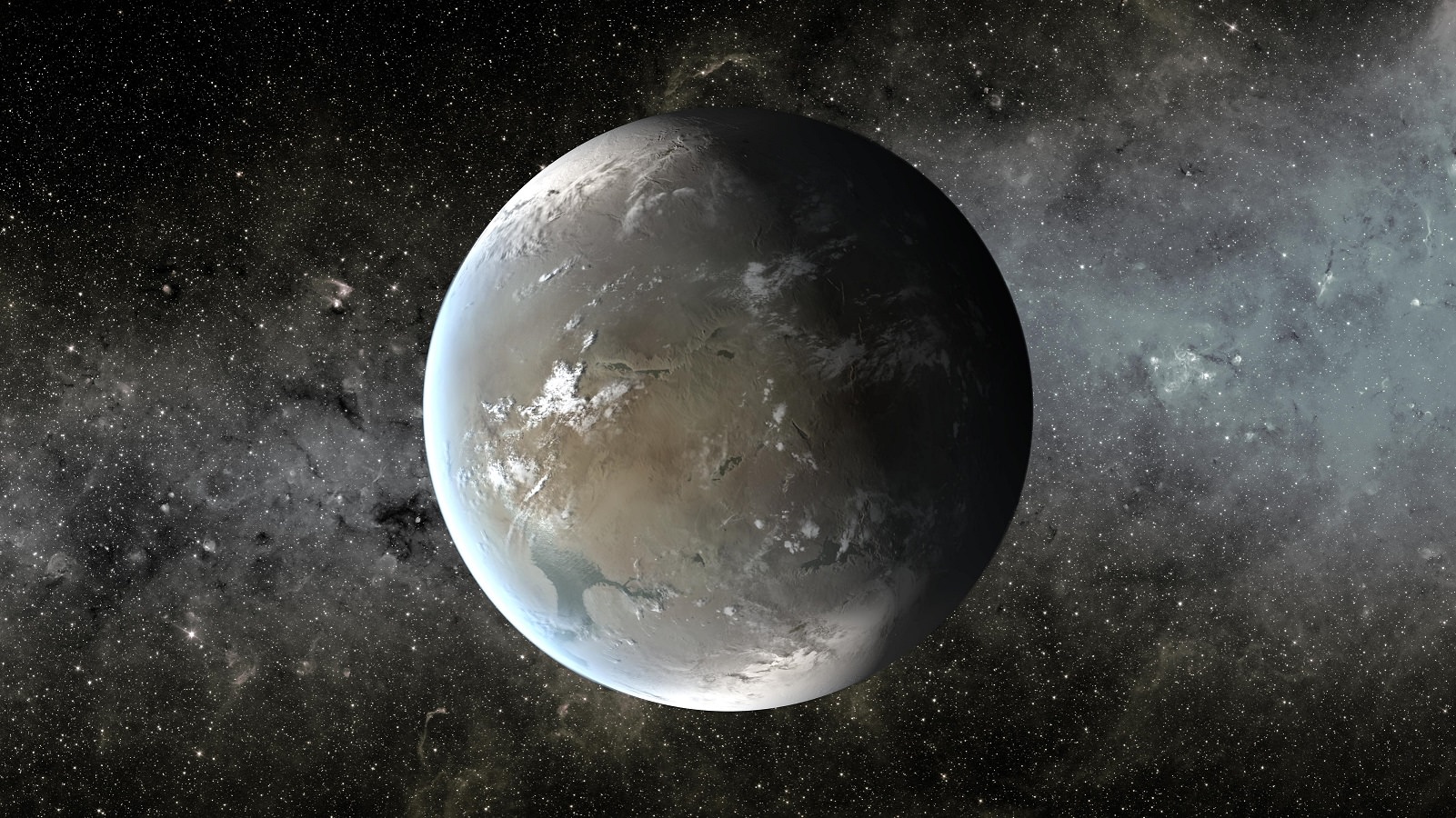

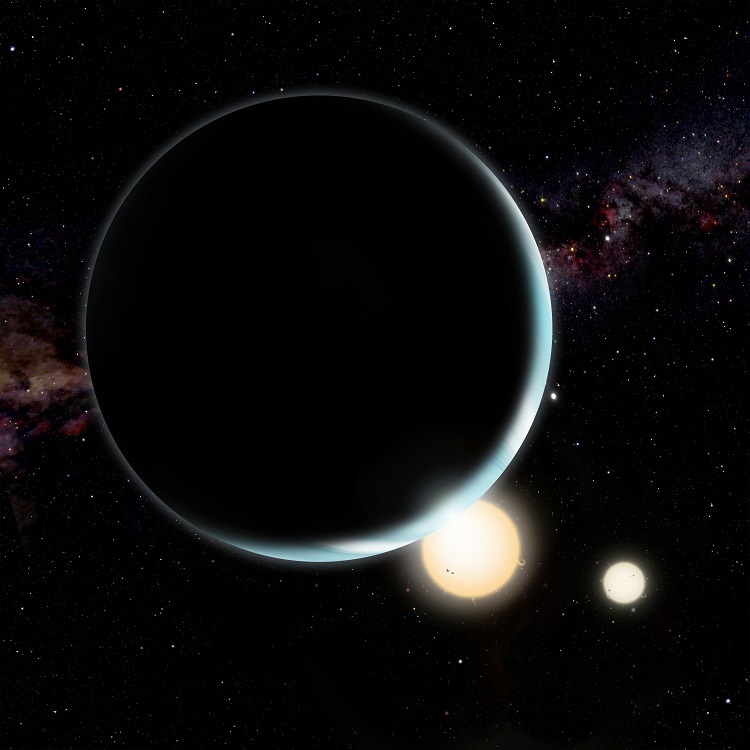

Alien planets that are slightly bigger than Earth could be more life-friendly than exoplanets closer to our own size, a new study implies. These so-called “super-Earths” that are about two to three times that of our own planet could be “superhabitable” — implying that our own planet is a rare bird indeed when it comes to being good for life.

Bigger rocky planets would have a host of advantages, argue McMaster University’s Rene Heller and Weber State University’s John Armstrong in a paper recently published in Astrobiology. Among them: These worlds would have tectonic activity that takes longer to happen, meaning that the conditions would be more stable for life. Also, a bigger mass implies it’s easier to hang on to a thick atmosphere and to have “enhanced magnetic shielding” to hold a planet’s own against solar flares.

“Our argumentation can be understood as a refutation of the Rare Earth hypothesis. Ward and Brownlee (2000) claimed that the emergence of life required an extremely unlikely interplay of conditions on Earth, and they concluded that complex life would be a very unlikely phenomenon in the Universe,” stated the authors in their paper “Superhabitable Worlds.”

“While we agree that the occurrence of another truly Earth-like planet is trivially impossible, we hold that this argument does not constrain the emergence of other inhabited planets. We argue here in the opposite direction and claim that Earth could turn out to be a marginally habitable world. In our view, a variety of processes exists that can make environmental conditions on a planet or moon more benign to life than is the case on Earth.”

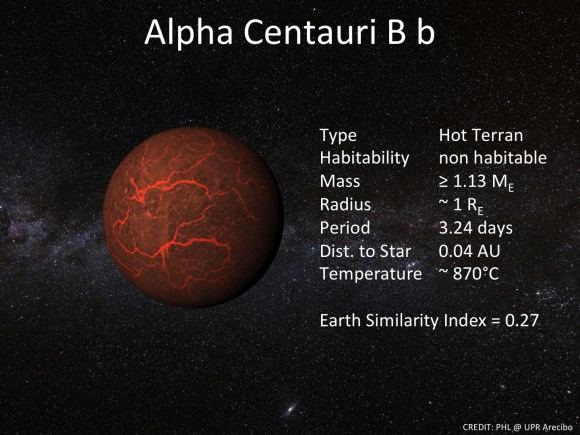

As a start, the scientists suggest looking at the Alpha Centauri system, where researchers in 2012 discovered a planet close to Earth’s size that is likely not habitable because it orbits so close to its sun.

The star system, however, is about the right age and has low enough radiation to allow life to occur on a planet or moon that “evolved similarly as it did on Earth”, providing the planet or moon “had the chance to collect water from comets and planetesimals beyond the snowline.” Further, it’s just four light-years from Earth, making it a good target for telescopic observations.

You can read more details of their research in Astrobiology or in preprint version on Arxiv.