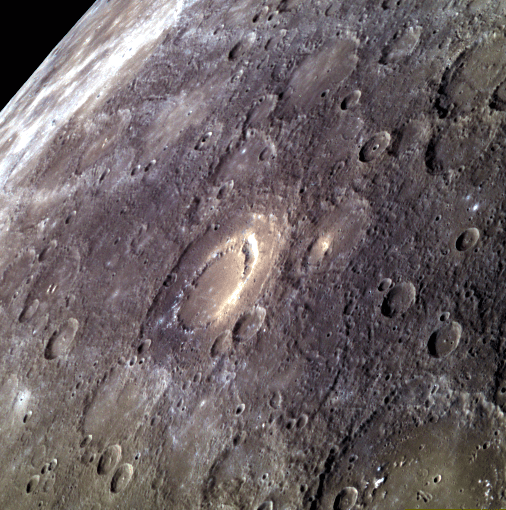

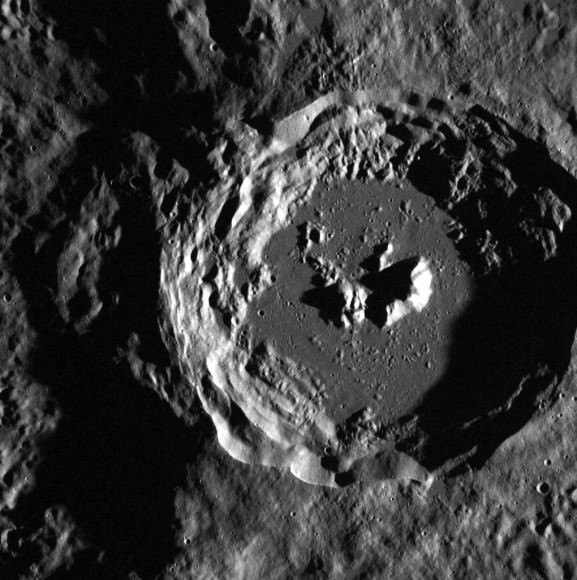

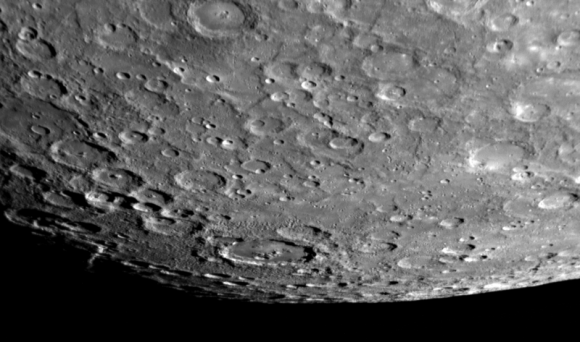

Here’s your rare chance to leave a lasting mark on a piece of the Solar System. The team behind the MESSENGER spacecraft — that machine orbiting Mercury since 2011 — is asking the public to help them name craters on the planet, in an open contest.

Fifteen finalists will be forwarded to the official arbitrator of astronomical names on Earth, the International Astronomical Union, which will pick five names in time for the end of the MESSENGER mission this spring.

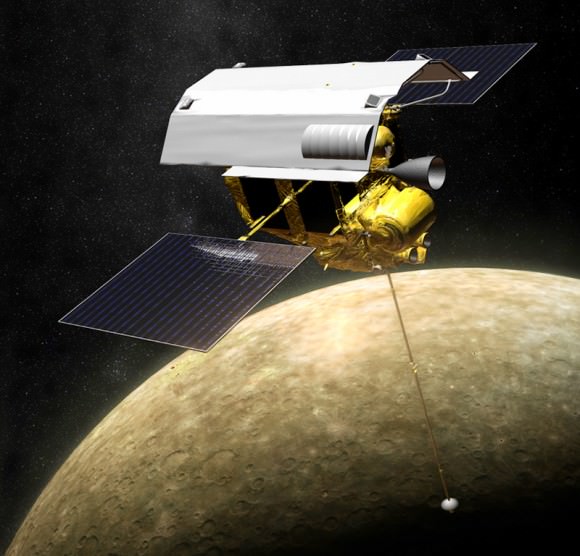

“This brave little craft, not much bigger than a Volkswagen Beetle, has travelled more than 8 billion miles [12.8 billion kilometers] since 2004—getting to the planet and then in orbit,” stated Julie Edmonds of the Carnegie Institution for Science, who leads the MESSENGER education and public outreach team.

“We would like to draw international attention to the achievements of the mission and the guiding engineers and scientists on Earth who have made the MESSENGER mission so outstandingly successful.”

Here are some guidelines to increase your chances of success:

– Make sure the name does not have significance politically, religiously or for the military;

– Focus on names of writers, artists and composers and research them thoroughly, as you will be expected to provide a justification;

– Don’t pick a name that has been used elsewhere in the Solar System.

Some additional hints come from the official contest website, which adds that the competition is open to everyone except MESSENGER’s education and public outreach team and that entries close Jan. 15.

Impact craters are named in honor of people who have made outstanding or fundamental contributions to the Arts and Humanities (visual artists, writers, poets, dancers, architects, musicians, composers and so on). The person must have been recognized as an art-historically significant figure for more than 50 years and must have been dead for at least three years. We are particularly interested in submissions that honor people from nations and cultural groups that are under-represented amongst the currently-named craters.

This isn’t the first planet with recent open invitations for the public to name craters. Earlier this year, astronomy education group Uwingu began asking for suggestions to name craters on Mars for maps that will be used by the Mars One team as it plans to land a private crewed mission on the planet in the coming years. Those names, however, will likely not be recognized by the IAU (the official statement is here.)