Captain Kirk has nothing on the “strange new worlds” the Kepler space telescope has found.

NASA’s planet-probing orbiting observatory launched its quest to find more Earths four years ago this week. Since then, it’s found thousands of planets ranging from ginormous gas giants to tiny rocky worlds that are even smaller than our planet. NASA extended its mission to 2016 last year, putting the telescope into planet-hunting overtime and, we assume, scientists into overdrive.

Along the way, Kepler has revealed some bizarre star systems. Check out some of the weirdest exoplanets Kepler has found so far:

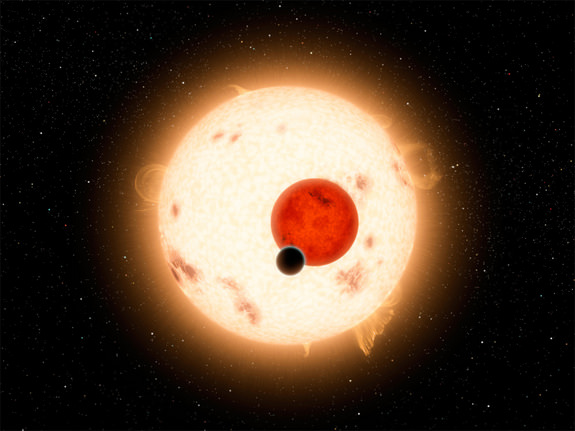

‘Tatooine’ (Kepler-16b)

“Circumbinary” is the scientific explanation for Kepler-16b’s 2 star-system. But “Tatooine” is the name that took the public by storm (or is that Stormtrooper?) when this world, orbiting two stars, was revealed in 2011. Although it’s named after Luke Skywalker’s home in Star Wars, proving Kepler-16b is habitable would be a bit of a stretch. The planet’s mass is about one-third that of Jupiter, and surface temperatures reach an estimated and frigid -100 degrees Celsius.

Deciphering a tune (Kepler-37b)

Scientists found Kepler 37-b through listening to its parent star sing. Seriously. The planet (just slightly larger than our moon) was revealed through measuring oscillations in brightness caused by star-quakes, then converting those to sound. “The bigger the star, the lower the frequency, or ‘pitch’ of its song,” said Steve Kawaler, a research team member from Iowa State University in a past Universe Today interview.

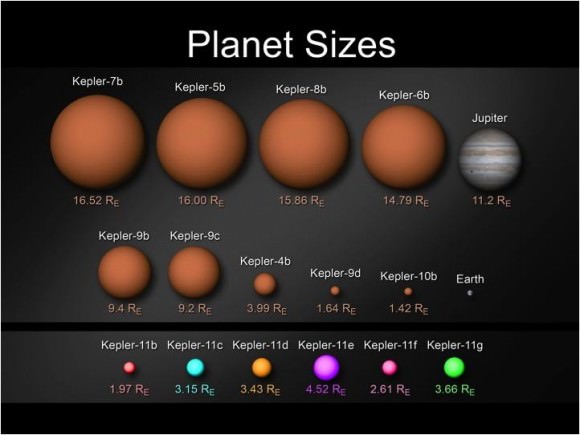

The 6-planet swarm (Kepler-11b, 11c, 11d, 11e, 11f, 11g)

It’s sure crowded around the star Kepler-11. There are six planets orbiting in circles smaller than Venus’ orbit around the Sun. Not only that, but five of those planets are even closer to their parent star than Mercury is to our sun. Excited astronomers said the system will rewrite planetary formation theories. “We really were just amazed at his gift that nature has given us,” said Jack Lissauer, co-investigator of the Kepler mission, in 2011. “With six transiting planets, and five so close and getting the sizes and masses of five of these worlds, there is only one word that adequately describes the new finding: Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious.”

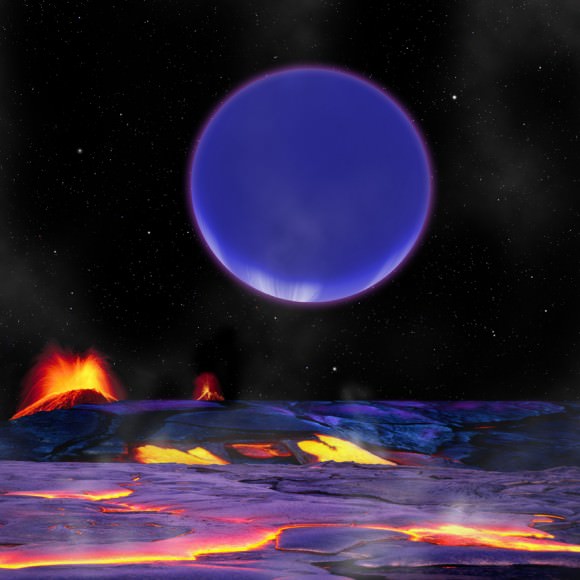

The warring siblings (Kepler-36b and 36c)

Credit: David A. Aguilar (CfA)

Take a planet the size of Neptune and put it near Earth, and you’d have some scary results. Tides from the constant interaction would raise the water and the ground, causing fissures and no end of local zoning headaches for municipal authorities as the ground shifts, to say the least. Seriously, though, Kepler-36b (the rocky world) comes within less than 5 Earth-Moon distances of Kepler 36-c (a gaseous world about 8 times larger) every 97 days or so. They’ll never crash into each other, but just like young human siblings, they can cause quite a bit of chaos.

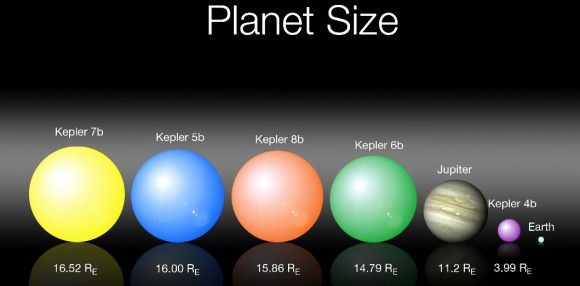

The mirror (Kepler-7b)

Well, Kepler-7b isn’t quite as reflective as a mirror, but it certainly catches more sunlight than scientists expected. This “hot Jupiter” was among the first planets that Kepler spotted. In 2011, however, it was revealed that its albedo, or reflectivity, flirted with the upper limit for these humongous planets. What’s causing this? Could be clouds, or could be the composition of its atmosphere. Shows we still have a lot to learn about these exoplanets.