The official name is “extra-vehicular activity,” (EVA) but most of us like to call it a spacewalk. However, when you think about it, you don’t really walk in space. You float.

Or more properly speaking, clutch on to handlebars as you make your way from spot to spot on your spacecraft as you race against the clock to finish your repair or whatever outdoor tasks you were assigned. But hey, the view more than makes up for the hard work.

Some astronauts actually got to fly during their time “outside.” During STS-41B 29 years ago this month, Bruce McCandless was the first one to strap on a jetpack and, in science fiction style, float a little distance away from the shuttle.

He called his test of the manned maneuvering unit “a heck of a big leap”. Nearly 30 years after the fact, it still looks like a gutsy move.

What other memorable floating NASA spacewalks have we seen during the space age? Here are some examples:

The first American one

The pictures for Ed White’s spacewalk on Gemini 4 still look amazing, nearly 48 years after the fact. The astronaut tumbled and spun during his 23-minute walk in space, and even tested out a small rocket gun until the gas ran out. When commander Jim McDivitt ordered him back inside, the astronaut said it was the saddest moment in his life.

The dancing-with-exhaustion one

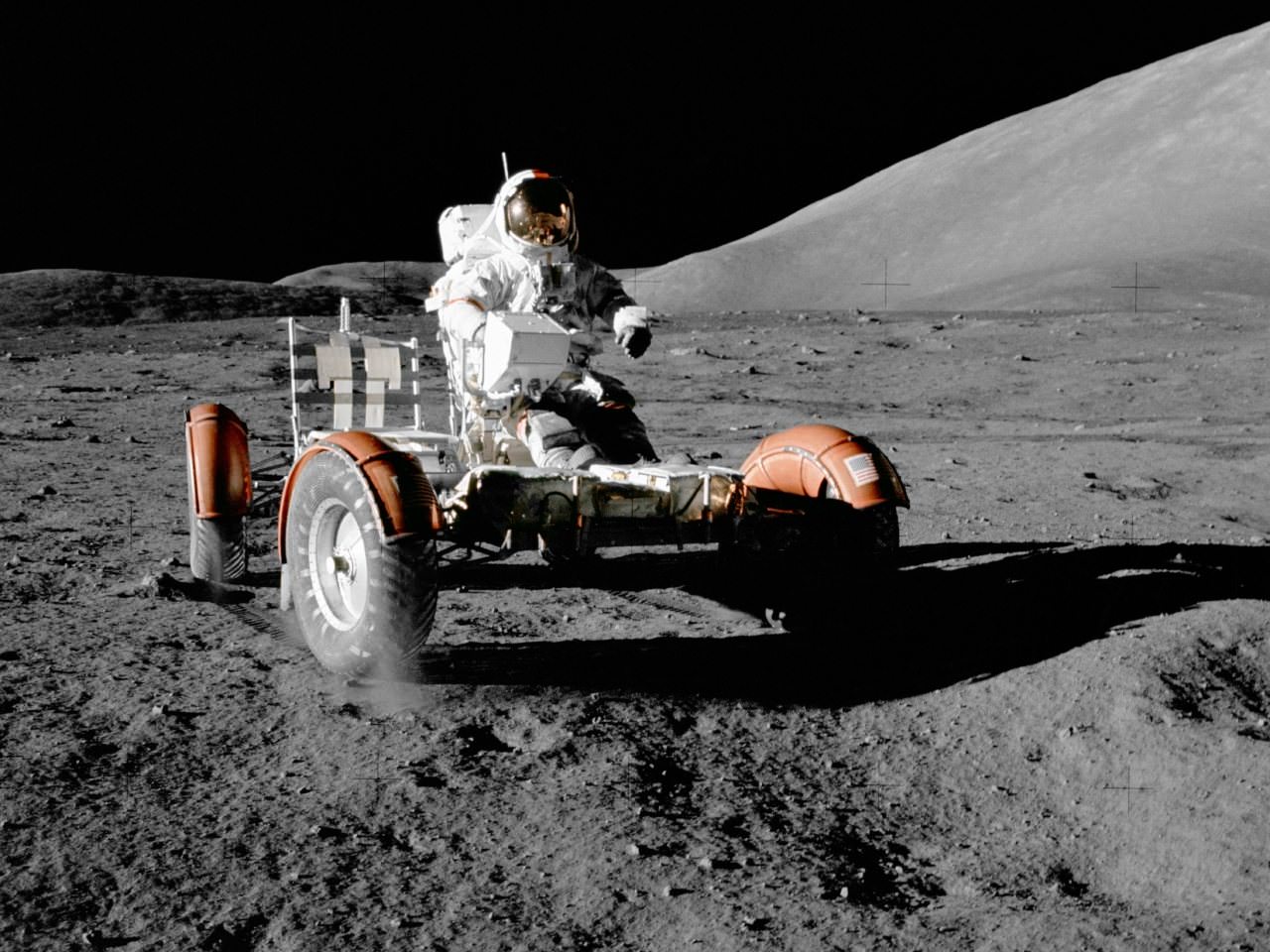

On Gemini 9, which took place the year after Gemini 4, Eugene Cernan was tasked with a spacewalk that was supposed to test out a backpack to let him move independently of the spacecraft.

Cernan, however, faced a lack of handholds and physical supports as he clambered outside towards the backpack. Putting it on took almost all the strength out of him, as he had nowhere to hold on to counterbalance himself.

“Lord, I was tired. My heart was motoring at about 155 beats per minute, I was sweating like a pig, the pickle was a pest, and I had yet to begin any real work,” Cernan wrote in his memoir, Last Man on the Moon, about the experience.

The situation worsened as his visor fogged up and Cernan struggled unsuccessfully to use the backpack. Cernan was so exhausted that he could barely get inside the spacecraft. “I was as weary as I had ever been in my life,” he wrote.

The three-astronauts-outside one

Spacewalks traditionally (at least, in the shuttle and station era) happen in pairs, so that if one person runs into trouble there’s another to help him or her out. However, two astronauts working outside during STS-49 couldn’t get enough of a grip on the free-flying Intelsat VI satellite they were trying to fix. So NASA elected to do another spacewalk with a third man.

Pierre Thuot hung on the Canadarm while Richard Hieb and Thomas Akers attached their bodies to the payload bay. Having three men hanging on to the satellite provided enough purchase for the astronauts inside the shuttle to maneuver Endeavour to a spot where Intelsat VI could be attached to the payload bay.

The facing-electrical-shock one

In 2007, the astronauts of STS-120 unfolded a solar array on the International Space Station and saw — to everyone’s horror — that some panels were torn. Veteran spacewalker Scott Parazynski was dispatched to the rescue. He rode on the end of the Canadarm2, dangling above a live set of electrified panels, and carefully threaded in a repair.

In an interview with Parazynski that I did several years ago, I asked how he used his medical training while doing the repair. Parazynski quipped something along the lines of, “Well, the top thing in my mind was ‘First do no harm.’ ”

The International Space Station construction ones

Spacewalks used to be something extra-special, something that only happened every missions or, on long-duration ones, maybe once. Building the International Space Station was different. The astronauts brought the pieces up in the shuttle and installed them themselves.

The station made spacewalking routine, or as routine such a dangerous endeavour can be. For that reason, an honorary mention goes to every mission that built the ISS.

What are your favorite EVAs? Feel free to add yours to the comments.