[/caption]

One of the great puzzles in science has been the evolution of single-celled organisms into the incredibly wide variety of flora and fauna that we see today. How did Earth make the transition from an initially lifeless ball of rock to one populated only by single-celled organisms to a world teeming with more complex life?

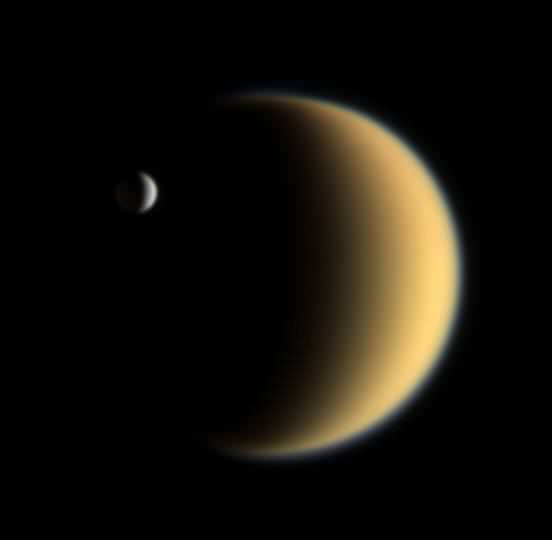

As scientists understand it, single-celled organisms first began evolving into more complex forms more than 500 million years ago, as they began to form multi-cellular clusters. What isn’t understood is just how that process happened. But now, biologists are another step closer figuring out this puzzle, by successfully replicating this key step – using an ingredient common in the making of bread and beer – ordinary Brewer’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae). While helping to solve evolutionary riddles here on Earth, it also by extension has bearing on the question of biological evolution on other planets or moons as well.

The results were published in last week’s issue of the Journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

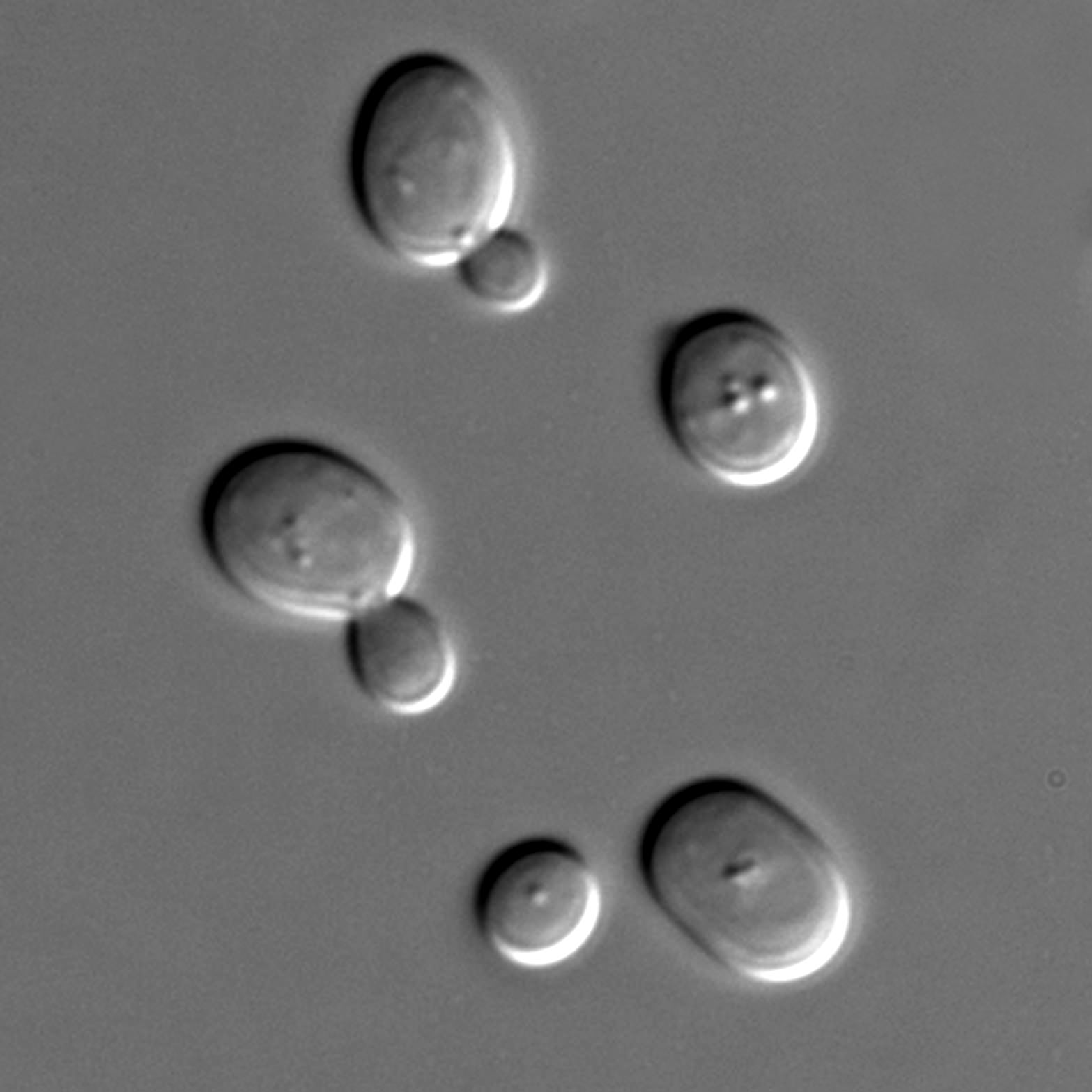

Yeasts are a microscopic form of fungi; they are uni-cellular but can become multi-cellular through the formation of a string of connected budding cells, like in molds. The experiments were based on this fact, and were surprisingly simple, they just hadn’t been done before, according to Will Ratcliff, a scientist at the University of Minnesota (UMN) and a co-author of the paper. “I don’t think anyone had ever tried it before,” he said, adding: “There aren’t many scientists doing experimental evolution, and they’re trying to answer questions about evolution, not recreate it.”

Sam Scheiner, program director in NSF’s Division of Environmental Biology, also adds: “To understand why the world is full of plants and animals, including humans, we need to know how one-celled organisms made the switch to living as a group, as multi-celled organisms. This study is the first to experimentally observe that transition, providing a look at an event that took place hundreds of millions of years ago.”

It’s been thought that the step toward multi-cellular complexity was a difficult one, an evolutionary hurdle that would be very hard to overcome. The new research however, suggests it may not be that difficult after all.

It took the first experiment only 60 days to produce results. The yeast was first added to a nutrient-rich culture, then the cells were allowed to grow for one day. They were then stratified by weight using a centrifuge. Clusters of yeast cells landed on the bottom of the test tubes. The process was then repeated, taking the cell clusters and re-adding them to fresh cultures. After sixty cycles of this, the cell clusters started to look like spherical snowflakes, composed of hundreds of cells.

The most significant finding was that the cells were not just clustering and sticking together randomly; the clusters were composed of cells that were genetically related to each other and remained attached after cell division. When clusters reached “critical mass,” some cells died, a process known as apoptosis, which allows the offspring to separate.

This then, simply put, is the process toward multi-cellular life. As described by Ratcliff, “A cluster alone isn’t multi-cellular. But when cells in a cluster cooperate, make sacrifices for the common good, and adapt to change, that’s an evolutionary transition to multi-cellularity.”

So next time you are baking bread or brewing your own beer, consider the fact that those lowly little yeast cells hold a lot more importance than just a useful role in your kitchen – they are also helping to solve some of the biggest mysteries of how life started, both here and perhaps elsewhere.