When astronomers detect new exoplanets they typically do so using one of two techniques. First, there’s the famous transit technique, which looks for slight dips in light as a planet passes in front of its host star, and second is the radial velocity technique, which senses the motion of a star due to the gravitational pull of its planet.

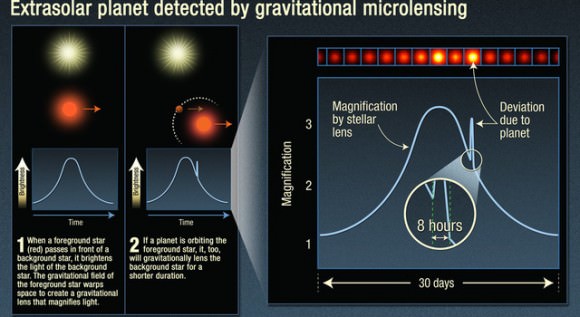

But then there is gravitational microlensing, the chance magnification of the light from a distant star by the mass of a foreground star and its planets due to the distortion in the fabric of spacetime. While this technique sounds almost improbable, it is so accurate that every detection skips nominating planets as candidates and immediately verifies them as bona-fide worlds.

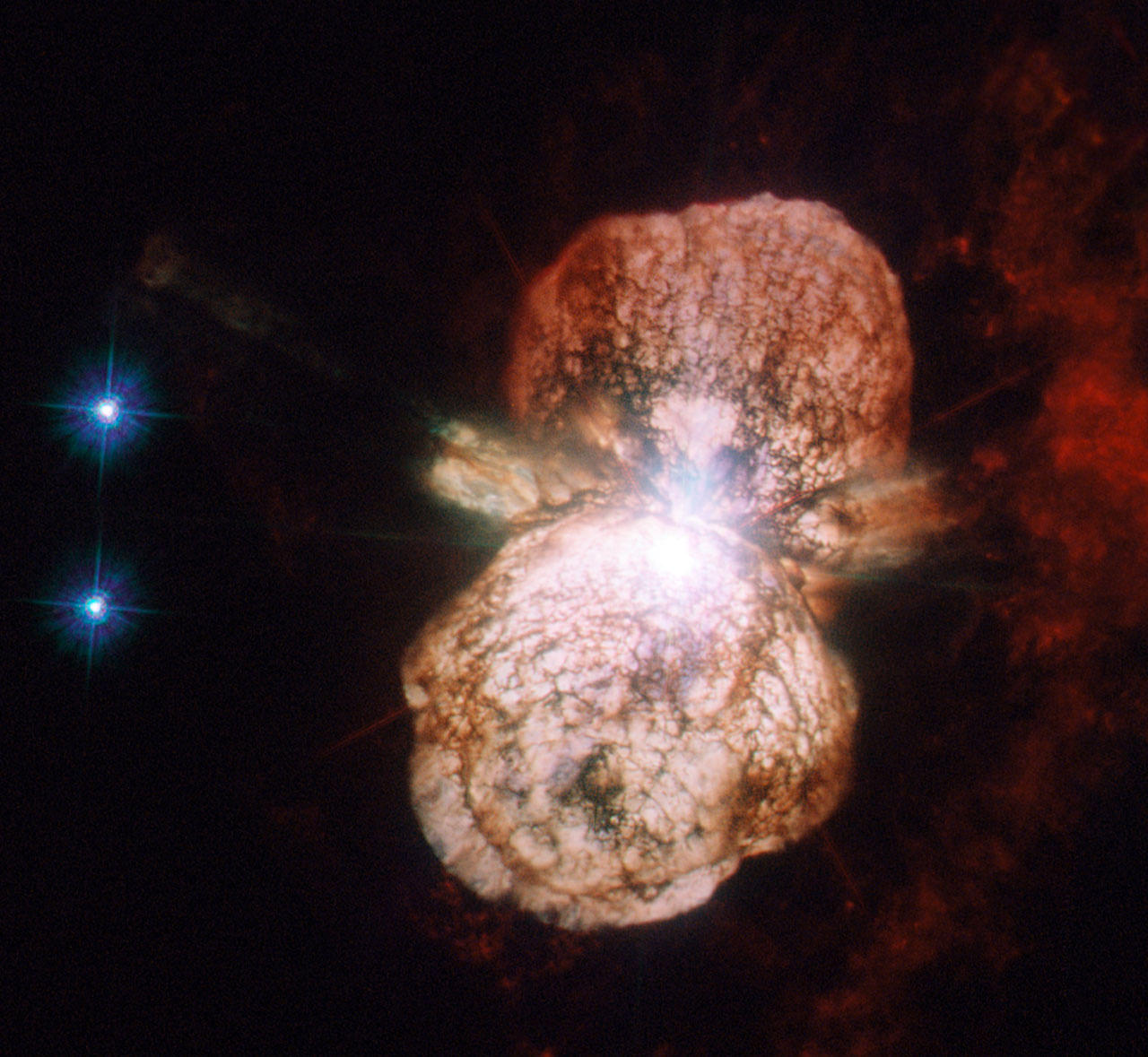

But without follow-up observations, the microlensing technique struggles with characterizing the incredibly faint host star. Now, a team of international astronomers led by PhD candidate Jennifer Yee from Ohio State University has detected the first microlensing signature, lovingly called MOA-2013-BLG-220Lb, that looks like a confirmed planet orbiting a candidate brown dwarf — an object so faint because it isn’t massive enough to kick-off nuclear fusion in its core.

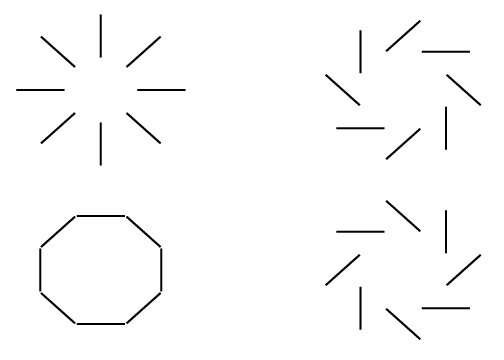

Matter — no matter how great or small — curves the fabric of spacetime. It can ultimately acts like a lens by curving the background light around it and therefore magnifying the background source. In microlensing, the intervening matter is simply a faint star or perhaps a planetary system.

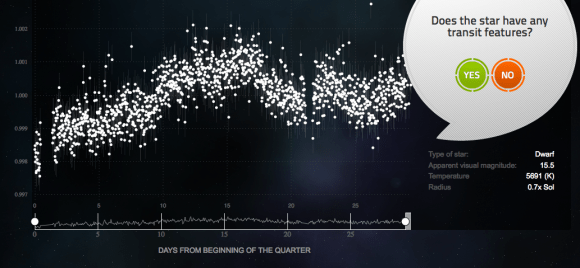

“As the ‘lens system’ passes in front of a distant, background star, the magnification of that background star changes as a function of time,” Yee told Universe Today. “By measuring the changing magnification of the background star, we can learn about the lensing star and perhaps whether or not it has a planet.”

In a planetary system, the light from the background star will be magnified when the foreground star passes in front of it. If there is a cirlcing planet, there will be an additional cusp in brightness (to a lesser extent but still a tell-tale detection nonetheless).

At the moment the planetary system transits in front of the background star (and for many years after) we can’t separate the two objects. While the light of the background star may be greatly magnified, its image is distorted because its light merges with the planetary system.

So the microlensing signature cannot tell astronomers anything about the lens system’s star. “It’s out of the ordinary,” Andrew Gould, Yee’s PhD advisor and coauthor on the paper, told Universe Today. “In other techniques people have definitely detected a star and they’re struggling to detect the planet. But microlensing is just the opposite. We detect the planet very clearly, but we can’t detect the host star.”

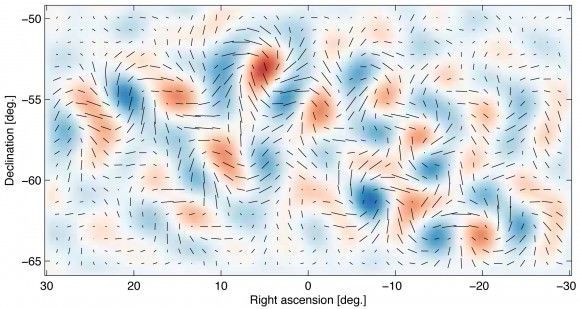

However, the microlensing signature does give away the lens system’s proper motion — the apparent change in distance over time — as it passes in front of the background star. MOA-2013-BLG-220Lb’s proper motion is extremely high, clocking in at 12.5 milliarcseconds (a distance on the sky that is 2400 times smaller than the size of the full moon) per year. This is roughly three times higher than average.

A high proper motion may be caused by an object that is very close by and is moving slowly or a very distant object moving rapidly. As most stars tend not to move at high speeds, the team assumes the object is relatively close, placing it at a distance of 6,000 light-years.

With a distance fixed, the team is also able to assume a mass for the object. It weighs in below the hydrogen-burning limit and is therefore considered the best brown dwarf candidate microlensing has detected.

“The double-edged sword of microlensing is that no light from the lens star is required,” Yee told Universe Today. “On the one hand, microlensing can find planets around dark or faint objects like brown dwarfs. The flip side is that it’s very difficult to characterize the lens star if its light is not detected.”

Astronomers will have to wait until 2021 to take a second look at the lens system. This time frame is how long we expect it to take before the candidate brown dwarf separates appreciably on the sky from the background star. Once it has done so astronomers will be able to verify whether or not the candidate is truly a brown dwarf.

The paper is available for download here.