Supernovae are surprisingly dependable. These brilliant and powerful explosions that mark the end of massive stars’ lives tend to shine anywhere from one hundred million to a few billion times brighter than the Sun for weeks on end. And their intrinsic brightness is always well known.

But in recent years a rare class of cosmic explosions, which are tens to hundreds of times more luminous than ordinary supernovae, has been discovered. And now one of these odd superluminous supernovae is mystifying astronomers further, with characteristics that simply don’t add up.

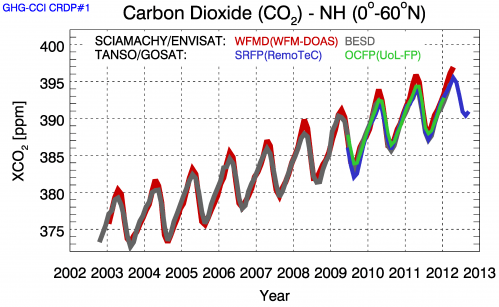

The Dark Energy Survey (DES) came online in August 2013 in order to investigate millions of galaxies for the subtle effects of weak lensing, the phenomenon where intervening invisible matter causes distant galaxies to appear minutely sheared and stretched.

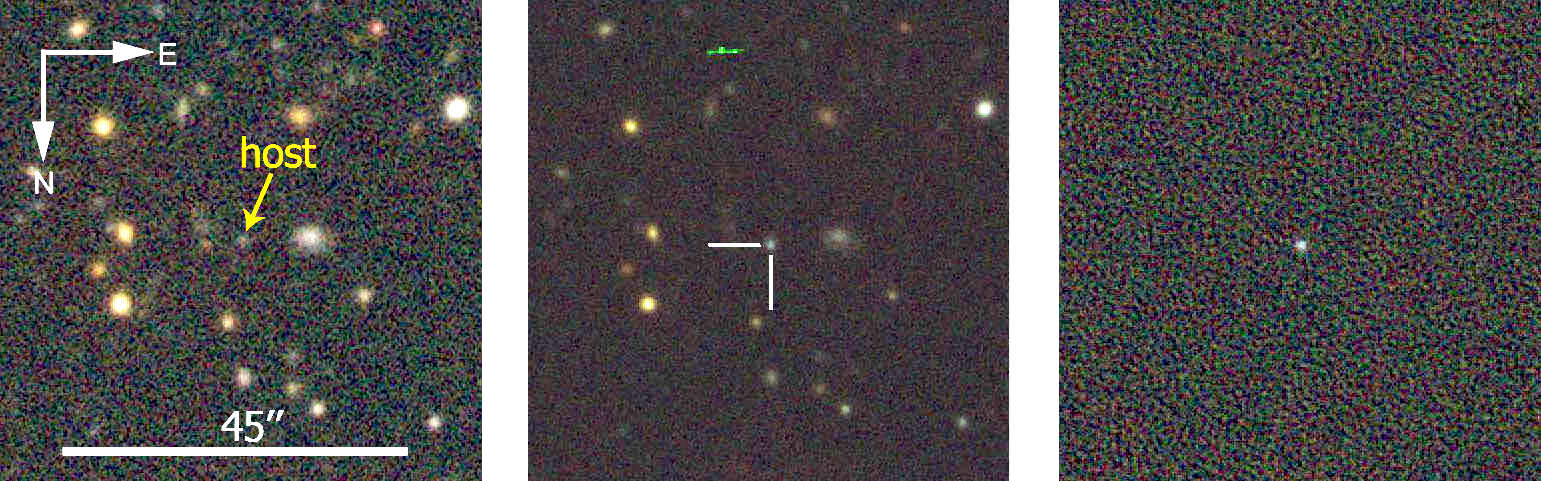

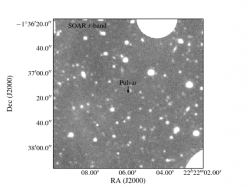

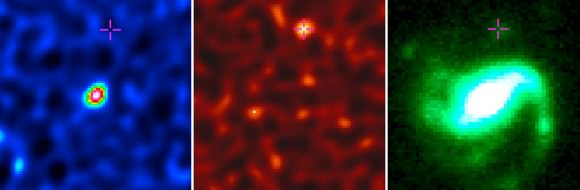

The survey started off with a bang; its first images revealed a rare superluminous supernova, dubbed DES13S2cmm, 7.8 billion light-years away.

“Fewer than forty such supernovae have ever been found and I never expected to find one in the first DES images,” said Andreas Papadopoulos from the University of Portsmouth in a press release. “As they are rare, each new discovery brings the potential for greater understanding — or more surprises.”

The problem is this: DES13S2cmm doesn’t easily match the typical characteristics of a superluminous supernova. The stellar explosion could be seen in the data six months later, much longer than most other superluminous supernovae observed to date.

“Its unusual, slow decline was not apparent at first,” said Mark Sullivan from Southampton University. “But as more data came in and the supernova stopped getting fainter, we would look at the light curve and ask ourselves, ‘what is this?’ ”

So Sullivan decided to investigate further. But understanding its origins are proving difficult.

For some supernovae, the optical light we see is actually created by radioactivity. In fact, supernovae tend to create large amounts of radioactive elements, which don’t occur naturally on Earth. Nickel-56, with a half-life of roughly six days, is a common example.

As the nickel decays into cobalt, it releases gamma rays, which are trapped by the other material ejected by the supernova. These trapped rays heat up the surrounding material until it radiates in the optical. In this case, the peak magnitude of the supernova is directly proportional to the amount of nickel-56 created in the explosion.

“We have tried to explain the supernova as a result of the decay of the radioactive isotope nickel-56,” said coauthor Dr Chris D’Andrea of the University of Portsmouth. “But to match the peak brightness, the explosion would need to produce more than three times the mass of our Sun of the element. And even then the behavior of the light curve doesn’t match up.”

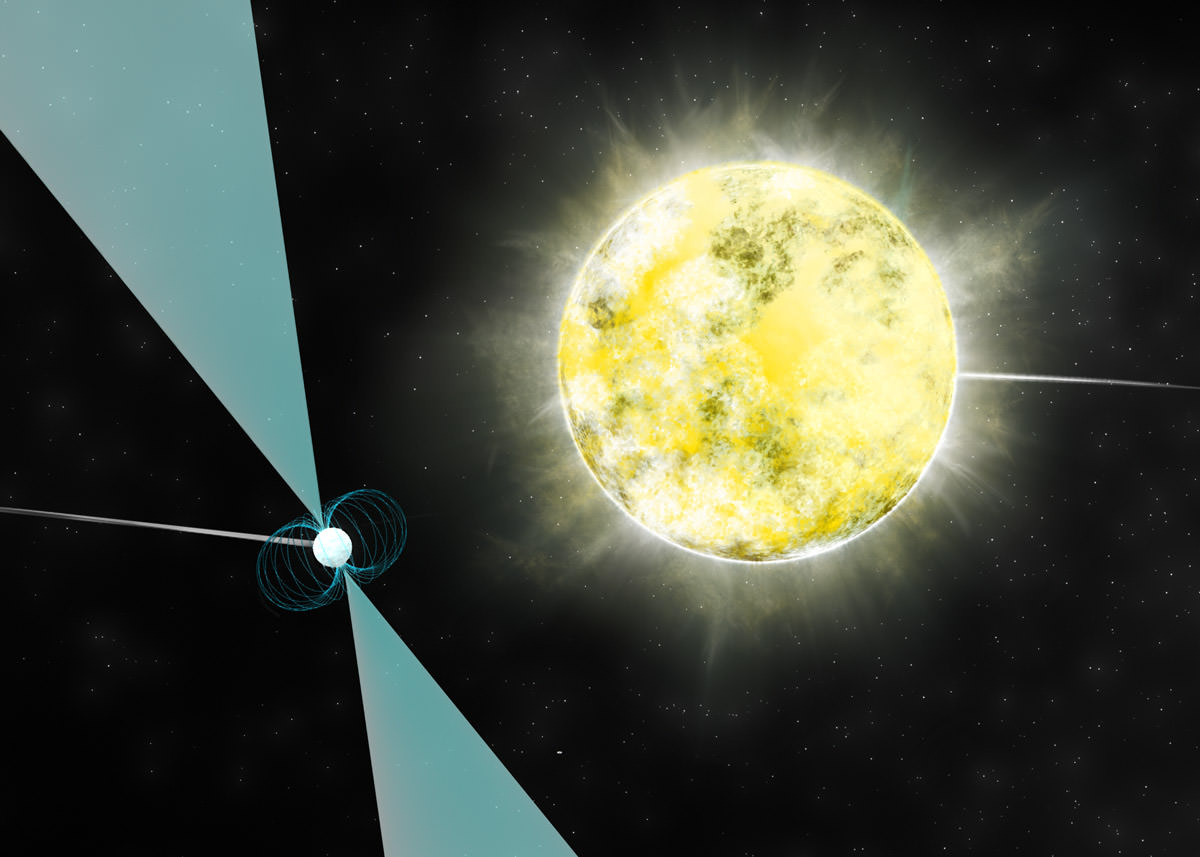

So the team is now investigating other explanations. In one intriguing scenario the supernova was relatively normal but created a magnetar — an extremely dense and highly magnetic neutron star that’s millions of times more powerful than the strongest magnets on Earth — whose energy made the explosion exceptionally bright.

But this explanation doesn’t match the data either.

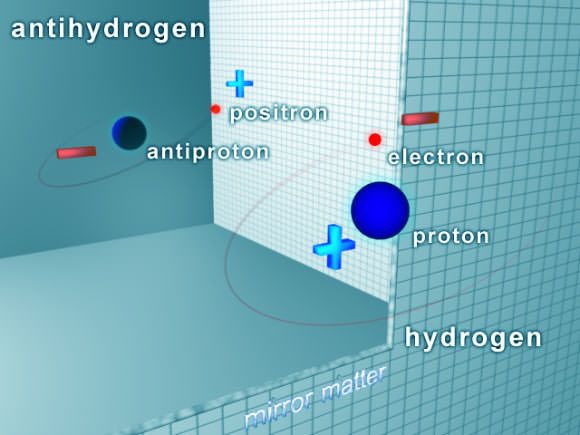

A few months ago a team of astronomers led by Robert Quimby explained a superluminous supernovae, PS1-10afx, by a chance cosmic alignment, where intervening matter worked like a lens to deflect and intensify the background light for a typical Type Ia supernova. D’Andrea, however, doesn’t believe this is the case here.

“DES13S2cmm looks nothing like a normal type of supernova, either in its photometric evolution or its spectroscopy,” D’Andrea told Universe Today. “So while we can never be sure that a very faint but very massive galaxy lies between us and another object and is serendipitously brightening the object, there is no need to adopt that assumption in the case of DES13S2cmm.”

chance cosmic alignment — where intervening matter worked like a lens to deflect and intensify the background light – See more at: http://www.skyandtelescope.com/astronomy-news/stellar-science/mysteriously-bright-supernova-explained/#sthash.m7Z8PJ3k.dpuf

chance cosmic alignment — where intervening matter worked like a lens to deflect and intensify the background light – See more at: http://www.skyandtelescope.com/astronomy-news/stellar-science/mysteriously-bright-supernova-explained/#sthash.m7Z8PJ3k.dpuf

So astronomers are heading back to the drawing board.

“With so few known, it’s hard to really understand their properties in detail,” said Bob Nichol from the University of Portsmouth. “DES should find enough of these objects to allow us to understand superluminous supernovae as a population. But if some of these discoveries prove as difficult to interpret as DES13S2cmm, we’re prepared for the unusual.”

The results will be presented today at the National Astronomy Meeting 2014 in Portsmouth.